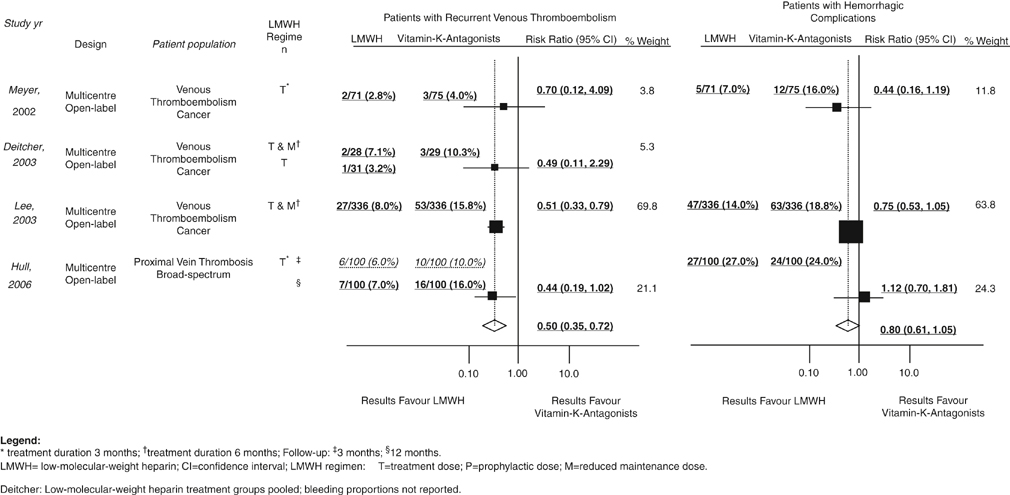

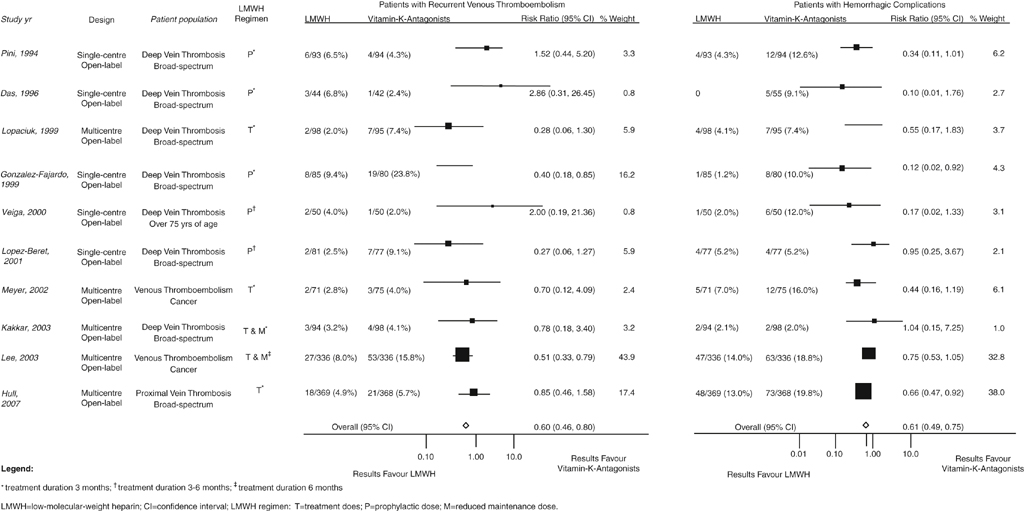

Two independent trials benchmarked the observation that LMWH was more effective than vitamin K–antagonist treatment for preventing recurrent VTE in cancer patients. Further clinical trial evidence suggests that LMWH therapy in this context is superior because patients with DVT are resistant to vitamin K–antagonist therapy. A brief course of subcutaneous LMWH was shown to be favorably influencing survival in patients with advanced malignancy. Individual trial findings for efficacy and safety with regard to recurrent VTE and hemorrhagic complications exist (Figure 1). A substantial clinical need also exists for an alternative to vitamin K–antagonist therapy for treating DVT in many patients other than cancer patients. A randomized trial evaluating self-managed LMWH therapy has provided further evidence on the balance of benefits and harms of its long-term use compared with long-term vitamin K–antagonist therapy suggested that LMWH had effectiveness similar to the usual vitamin K–antagonist treatment for preventing recurrent VTE in a broad spectrum of patients. Important clinically, however, is that long-term LMWH caused less harm as a result of bleeding and thus enhanced the clinicians’ therapeutic options for patients with DVT (Figure 2). This suggests the possibility of a broader range for long-term LMWH in selected patients without cancer.

Nonoperative Treatment of Acute Lower Extremity Venous Thrombosis

Patients with Deep Vein Thrombosis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Thoracic Key

Fastest Thoracic Insight Engine