FIGURE 14.1. Raynaud’s attack in a 47-year-old woman shows various stages of pallor, cyanosis, and rubor.

Patients with Raynaud’s syndrome are traditionally divided into two groups.1 The term Raynaud’s disease is used to describe a benign idiopathic form of intermittent digital ischemia occurring in the absence of known associated diseases. Raynaud’s phenomenon is used to describe similar symptoms occurring in association with a variety of underlying disease states. It is well recognized that the presence of an underlying disease may not be established at the time a patient presents with Raynaud’s syndrome.2 Therefore, the distinction between Raynaud’s disease and Raynaud’s phenomenon is somewhat artificial and uncertain. The clinical manifestations of Raynaud’s syndrome should be considered as symptoms requiring a diagnosis rather than a diagnosis in itself. In most cases, the diagnosis will be episodic vasospasm without a known associated underlying condition. In cool, damp climates, 6% to 20% of the population, particularly young females, will report symptoms of Raynaud’s syndrome.

In about 5% of cases, an underlying condition will be discovered in association with Raynaud’s syndrome. The vascular laboratory can play an important role in separating benign episodic vasospasm (Raynaud’s disease) from vasospasm associated with serious underlying conditions requiring medical or surgical management (Raynaud’s phenomenon).4,5 With the exception of vasospastic episodes induced by vasopressor medications or ergot, vasospasm alone very rarely results in tissue loss or ulceration. The presence of ulceration or digital gangrene should trigger a workup to confirm the presence of digital artery occlusive disease and an associated condition (Fig. 14.2).

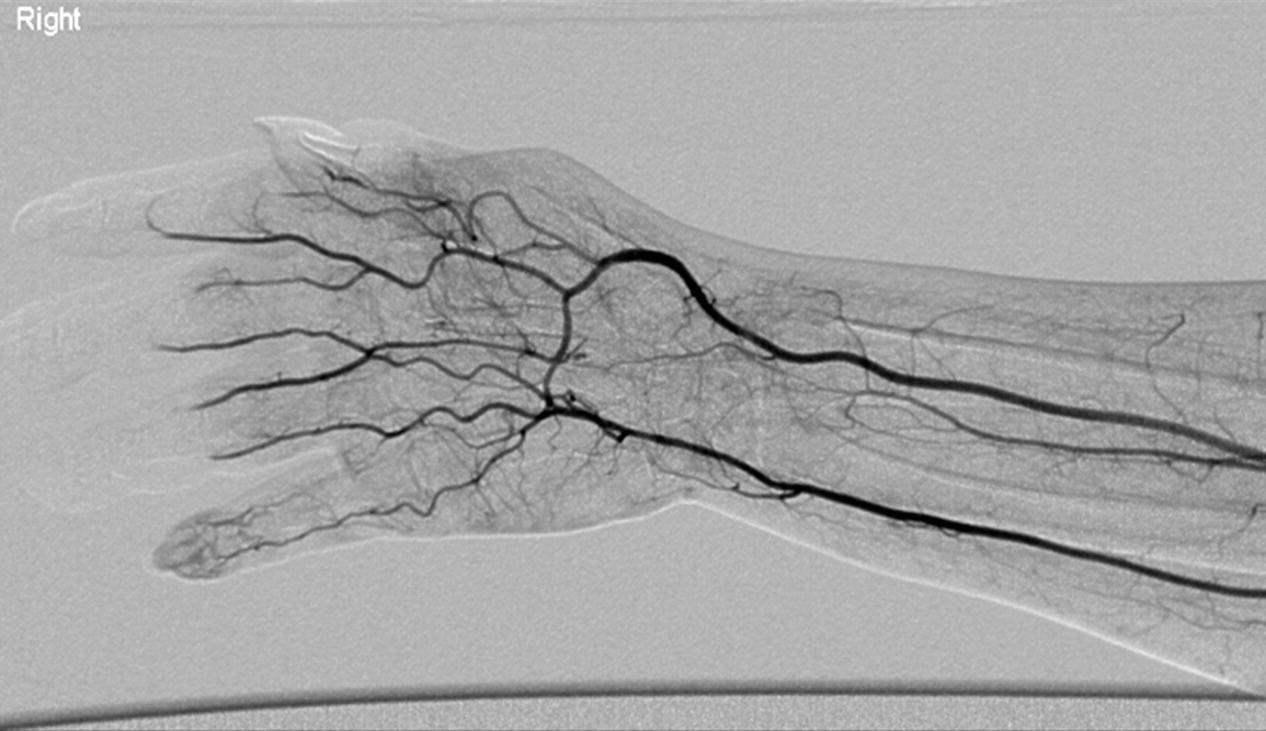

FIGURE 14.2. Arteriogram of digital artery occlusions from a proximal embolic source. Note the lack of filling in the arteries of the index, middle, and ring fingers.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

A useful classification scheme for both the diagnosis and the treatment of upper extremity ischemia is to use the physical examination and the vascular laboratory to divide patients into those with large artery disease and those with small artery disease. Patients are then further divided into those with vasospasm alone and those with arterial obstruction (with or without vasospasm) based on vascular laboratory and serologic testing.

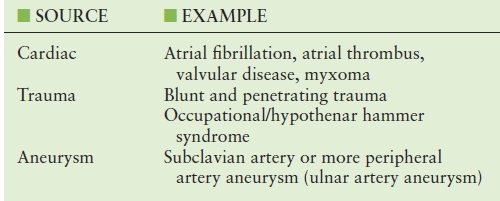

Small artery occlusive disease accounts for 90% to 95% of patients presenting with upper extremity ischemia, ulceration, or gangrene (Table 14.1). Small artery occlusive disease may be relatively benign and apparent only as intermittent cold sensitivity of the fingertips. Large artery diseases generally produce serious upper extremity symptoms by embolization to the digital arteries (Table 14.2). Occlusive disease of the subclavian artery, although very common, is rarely a cause of limb-threatening upper extremity ischemia unless complicated by embolization to the forearm, palmar, or digital arteries.

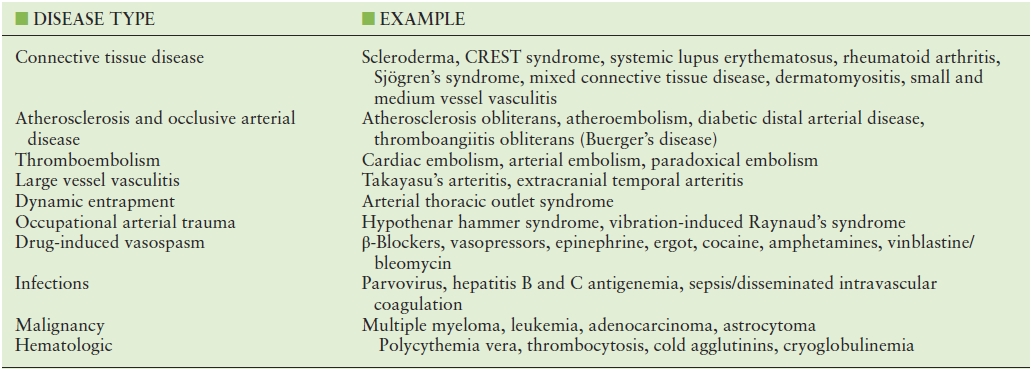

TABLE 14.1 Diseases Associated with Intrinsic Digital Artery Occlusions

CREST, calcinosis cutis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysfunction, sclerodactyly, telangiectasia.

TABLE 14.2 Conditions Resulting in Embolization to the Upper Extremity Digital Arteries

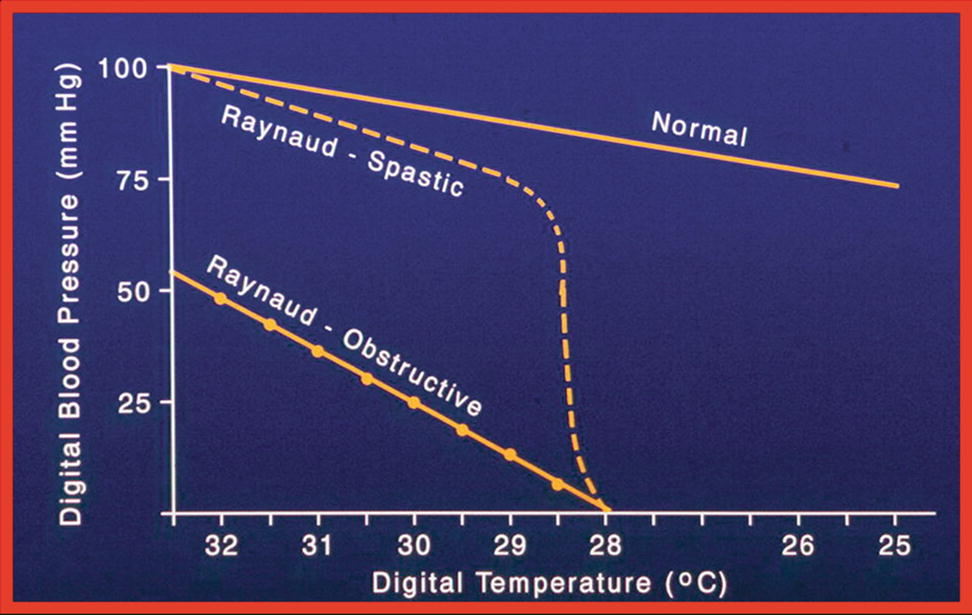

Patients with purely vasospastic Raynaud’s syndrome do not have significant proximal, palmar, or digital artery obstruction and accordingly have normal digit pressures at room temperature. However, a markedly increased force of cold-induced vasospasm causes arterial closure in these patients. Patients with obstructive Raynaud’s syndrome have significant occlusive lesions in the arteries between the heart and the distal phalanx of the digit. To experience a Raynaud’s attack, the patient must have sufficiently severe arterial obstruction to cause a significant reduction in the resting digit pressure. This requires obstruction of both digital arteries in a single digit. In such patients, a normal vasoconstrictive response to cold is sufficient to overcome the diminished intraluminal distending pressure and cause arterial closure. This theory predicts that all patients with hand arterial obstruction sufficient to cause resting digital hypotension will experience cold-induced Raynaud’s attacks.6 Figure 14.3 schematically demonstrates the relationship between finger pressure and finger temperature for normal individuals and patients with vasospastic or obstructive Raynaud’s syndrome.

FIGURE 14.3. Finger pressure and temperature in normal individuals and patients with Raynaud’s syndrome. The normal response to cold is a linear decline in digital artery pressure. The vasospastic Raynaud’s patients have a steeper decline in pressure until a threshold temperature is reached, followed by near-instantaneous occlusion. The obstructive Raynaud’s patients have lower normothermic digital artery pressures and a near-normal vasoconstrictive response to cold.

NONINVASIVE DIAGNOSTIC TECHNIQUES

Noninvasive vascular laboratory testing of the upper extremity arteries begins with a physical examination. The fingers should be carefully inspected for the presence of ulcers. Hyperkeratotic areas are suggestive of healed ulcers. The hands and fingers should also be examined for telangiectasias, skin thinning, tightening, or sclerodactyly, indicating an associated autoimmune disease. Signs and symptoms of nerve compression syndrome should also be sought. Carpal tunnel syndrome is seen in about 15% of Raynaud’s patients.7 While the physical examination is frequently completely normal in patients with Raynaud’s syndrome, a complete pulse examination of all extremities must be performed with attention to the strength and quality of pulses as well as the presence of aneurysms or bruits.

Segmental Arm Pressures

No special patient preparation is required for measurement of segmental arm pressures. Upper extremity segmental pressures are obtained by measuring systolic blood pressure with pneumatic cuffs placed above the elbow, below the elbow, and above the wrist while insonating the radial or ulnar artery at the wrist with a continuous-wave Doppler. Doppler-derived waveforms or plethysmographic waveforms can also be recorded at the different levels. Abnormal waveforms or pressures indicate arterial occlusive disease proximal to the wrist.

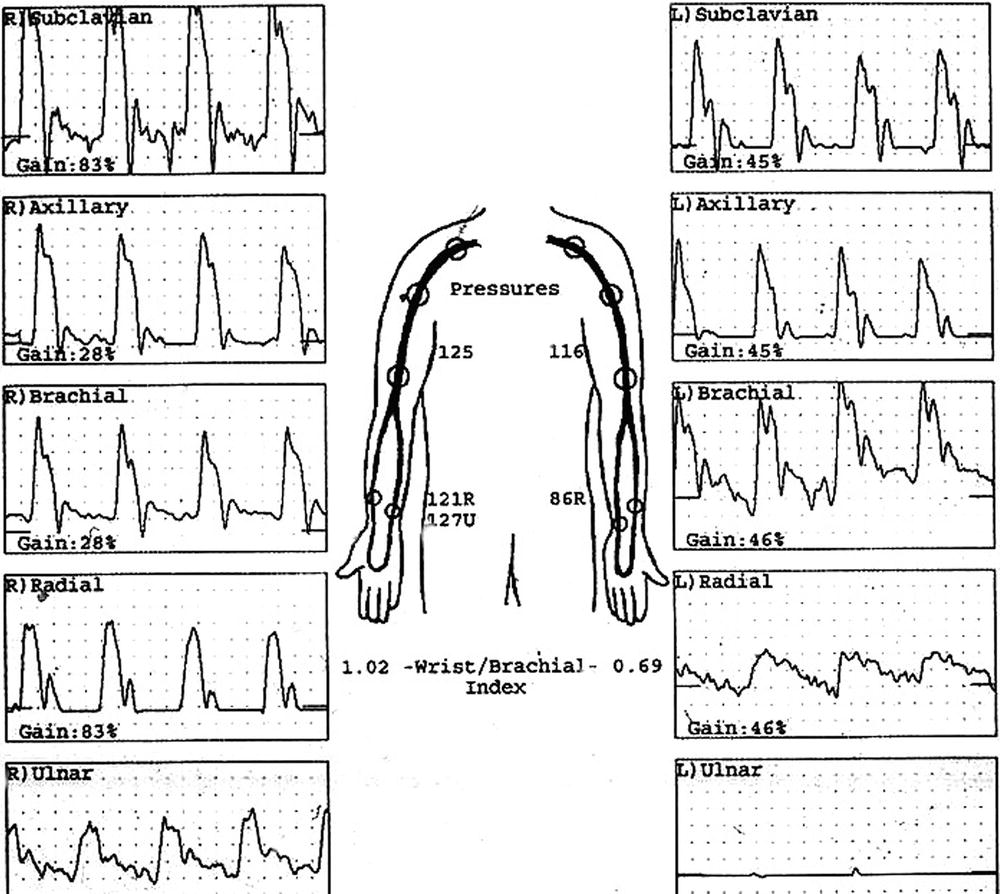

A 12-cm-wide blood pressure cuff is usually sufficient for measuring the systolic pressure above the elbow (brachial artery), whereas 10-cm-wide cuffs are used below the elbow and above the wrist (radial and ulnar arteries). However, in general, cuff width should be at least 50% greater than the diameter of the limb in which pressure is being measured. The use of smaller cuffs results in the recording of falsely high pressures. Normally, the gradient between adjacent levels is minimal, and a normal wrist-to-brachial blood pressure ratio is 1.0. If the systolic blood pressure difference between the two arms is more than 15 mm Hg, it is likely that there is a stenosis or occlusion somewhere on the side with the lower pressure. Abnormal Doppler waveforms and decreased pressures at the above-elbow cuff site indicate axillary, subclavian, or brachiocephalic arterial occlusive disease. Similarly, abnormalities at the below-elbow and above-wrist sites indicate brachial and proximal ulnar/radial arterial occlusive disease, respectively. If the blood pressure difference is more than 15 mm Hg between adjacent levels, or between the radial and ulnar arteries, it is likely due to a stenosis or occlusion (Fig. 14.4).

FIGURE 14.4. Segmental arm pressures and Doppler waveforms demonstrate abnormal pressures and waveforms from the radial and ulnar arteries in the left upper extremity. The study indicates arterial occlusive disease distal to the brachial artery in the left upper extremity.

Digit Pressures and Plethysmography

It is important to measure and record finger temperature before performing digital plethysmography and obtaining finger blood pressures. If the finger temperature is less than 28°C to 30°C, false-positive results may occur secondary to cold-induced vasospasm. Hand or whole-body warming should be performed in patients with low finger temperatures. The technologist should record the finger temperatures to ensure the interpreting physician that the chances of vasospasm have been minimized.

Photoplethysmography (PPG) or strain-gauge plethysmography can be used to measure digit blood pressure5 and obtain volume pulse waveforms. Alternating current ([AC]-coupled) PPG is preferred because the equipment is easier to use and more durable. An additional advantage of PPG is that it is possible to record the volume pulses from the tips of the digits. This may be useful in documenting obstruction localized to the digital arteries.

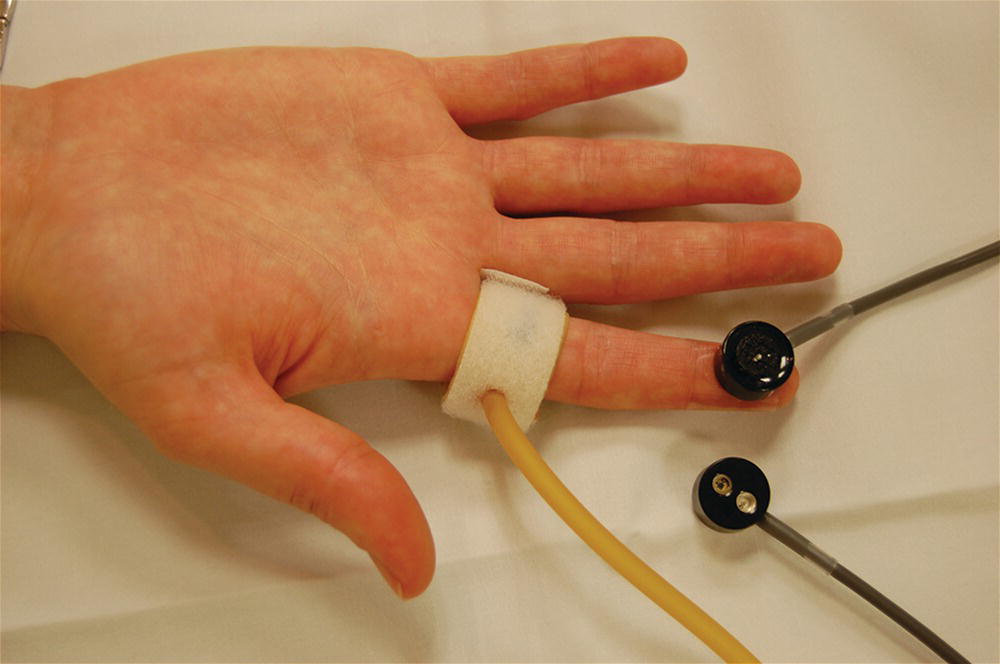

The PPG photocell is attached to the fingertip pulp with double-sided tape, or a small strain gauge is placed around the fingertip. A 1-inch-(2.5-cm)-wide digital blood pressure cuff is placed around the proximal phalanx (Fig. 14.5). The volume pulse waveforms are recorded using a high sweep speed. This allows the shape of the waveform to be evaluated. Normal waveforms show a rapid upstroke with a time of less than 0.2 second. They may or may not have a prominent dicrotic notch (Fig. 14.6A). An abnormal obstructive waveform will have a prolonged upstroke time and a flattened, rounded peak (Fig. 14.6B). Patients with vasospasm will often have an abnormally shaped waveform termed a peaked pulse. These waveforms are thought to represent abnormal elasticity and rebound of the palmar and digital vessels (Fig. 14.6C). The amplitude of the digit volume pulse waveforms is not important. Digit PPG waveforms are not quantitative, and the amplitude depends on the gain setting of the instrument, not blood flow.

FIGURE 14.5. Application of a finger cuff and a photocell to obtain finger photoplethysmography (PPG) recordings and digit pressures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree