13 Non–ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction

The incidence and potential severity of ACS makes timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment essential for minimizing morbidity and mortality. Every year in the United States, approximately 2.5 million patients are admitted to a hospital with an ACS. Two thirds of these individuals are eventually diagnosed with unstable angina or non–ST-elevation MI. This chapter focuses on diagnosis and treatment of patients in the ACS subgroup called non–ST-elevation ACS. Patients diagnosed with ST-elevation MI are discussed in Chapter 14.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

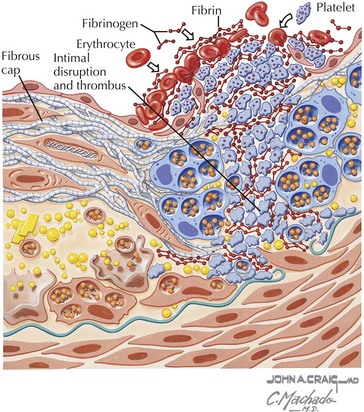

Several processes can result in an oxygen supply inadequate to meet myocardial demand, the hallmark of ACS. Most patients with an ACS share a common underlying pathophysiology: rupture of an atherosclerotic coronary artery plaque followed by the acute formation of a nonobstructive thrombus (Fig. 13-1). Plaque erosion, characterized by adherence of a thrombus to the plaque surface without an associated disruption of the plaque, is another mechanism of coronary thrombosis. Autopsy series have shown that the prevalence of plaque erosion—as opposed to plaque rupture—as the primary event in ACS is 25% to 40%. The frequency of plaque erosion is higher in women than in men.

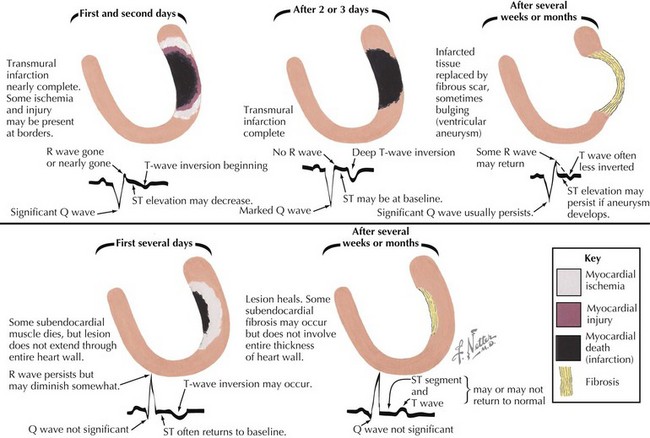

As illustrated in Figure 13-2, there are important differences in the pathophysiology of non–ST-elevation versus ST-elevation MI. The treatment of these two entities, and the long-term sequelae are also different.

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical manifestations of myocardial ischemia can be mimicked by many other processes (see also Chapter 1). Musculoskeletal disorders involving the cervical spine, shoulder, ribs, and sternum can result in nonspecific chest discomfort and even pain syndromes that are similar to angina pectoris. Symptoms from gastrointestinal causes, including esophageal reflux with associated spasm, peptic ulcer disease, and cholecystitis, are often indistinguishable from angina. Intrathoracic processes such as pneumonia, pleurisy, pneumothorax, aortic dissection, and pericarditis can produce chest discomfort. Finally, panic attacks and hyperventilation are neuropsychiatric syndromes that can be mistaken for ACS.

Diagnostic Approach

Electrocardiogram

The resting ECG is a key component for assessment of patients with suspected ACS. ST-segment and T-wave changes are the most reliable electrocardiographic indicators of myocardial ischemia (Fig. 13-2). Twelve-lead electrocardiography, performed when symptoms are present, is particularly valuable. Ideally, recordings should be obtained while symptoms are and are not present. When possible, the ECG tracing should be compared with a previous tracing, taken in the absence of chest discomfort. If transient ST-segment or T-wave changes are identified, the patient probably has acute myocardial ischemia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree