Neurogenic Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

ROBERT W. THOMPSON and CHANDU VEMURI

Presentation

A 28-year-old female postal clerk presents to your office with a 3-year history of left hand, arm, and neck pain. She also experiences left upper extremity numbness and tingling that are aggravated by use, especially with the arm elevated, as well as occipital headaches. All of these complaints began several months after an automobile collision in which the patient suffered a hyperextension strain to the neck but had no definitive cervical spine injury. Her symptoms did not improve with several courses of physical therapy, and she was advised to continue working despite the discomfort. Over the past year, she eventually found it too painful to work; her symptoms progressed to the extent that she often has difficulty sleeping at night. The patient has seen seven different physician specialists over the past 2 years without insight into the cause of her symptoms, and she has not experienced any symptomatic improvement with a variety of different treatment modalities. Previous evaluations have included cervical spine and shoulder radiographs, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and neck, and nerve conduction and electromyography studies. The results from all of these tests have been described as normal.

Differential Diagnosis

A large number of conditions have to be considered in the initial differential diagnosis of this patient’s symptoms. This list includes cervical spine arthritis, degenerative disc disease or spinal stenosis, posttraumatic cervical spine strain, and fibromyalgia of the trapezius muscles. Shoulder tendinitis or other degenerative joint conditions should also be considered, along with acromioclavicular impingement syndrome, epicondylitis, ulnar nerve (cubital tunnel) entrapment syndrome, and median nerve (carpal tunnel) compression syndrome. The diffuse and nonspecific nature of her complaints might also make it necessary to consider a peripheral neuropathy or multiple sclerosis. Given the frequent lack of objective findings on previous evaluations, it is also important to include even psychogenic causes of her symptoms and the possibility of secondary gain.

Diagnostic Testing

Most of the entities in this differential diagnosis can be evaluated either by specific elements of the physical examination or by diagnostic tests that yield positive findings in the presence of the condition. For example, the presence of degenerative cervical spine disease or disc herniation on CT scan or MRI could provide definitive evidence of these conditions. Alternatively, negative test results can also definitively exclude some of the diagnoses in question; thus, the absence of focal slowing of nerve conduction over the wrist excludes carpal tunnel syndrome. In this case, the results of previous evaluations have effectively eliminated a problem restricted to the cervical spine, the shoulder joint, or a single peripheral nerve distribution. In this situation, a diagnosis of neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) begins to emerge as a distinct possibility.

Neurogenic TOS is an uncommon condition often not considered until other entities have been excluded, and there is ongoing symptomatic deterioration. Unfortunately, there are no single aspects of the physical examination or specific diagnostic tests that can confirm or exclude a diagnosis of neurogenic TOS. Establishing a diagnosis of neurogenic TOS thereby depends on a constellation of subjective symptoms and corroborative findings on physical examination that fit into a typical clinical pattern, combined with the exclusion of other, more common conditions.

Case Continued

Physical examination reveals a cool left hand without signs of ischemia, thromboembolism, or venous congestion. The left arm has a full range of motion with pain, numbness, and tingling induced by abduction to 180 degrees. There is tenderness upon palpation of the left supraclavicular space with reproduction of left hand symptoms. Muscle spasm is detectable along the border of the left trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles. There are pain and tenderness along the medial border of the scapula.

In performing the Adson’s test, the left radial artery pulse is not easily palpable with the arm at rest but is present. The pulse seems to dampen with the arm positioned at 90 degrees abduction or higher. The right radial pulse is also diminished at rest but is palpable in all arm positions. The patient is unable to complete a 3-minute elevated arm stress test (EAST), due to the development of severe left arm and hand pain within 10 seconds of arm elevation. Examination of the right upper extremity is completely normal.

On moderate palpation of the left infraclavicular subcoracoid space, the patient reports a reproduction of symptoms similar to those aggravated by repetitive use of the arm. Furthermore, with the patient’s hand pressed against yours and flexion of the pectoralis major muscle, the symptoms induced by subcoracoid palpation are relieved.

Diagnosis

The most probable diagnosis is left neurogenic TOS with brachial plexus compression at the level of the scalene triangle and the subcoracoid (pectoralis minor) space. The factors supporting the diagnosis are the history of previous neck trauma and progressive symptoms affecting the entire arm and hand. The absence of a previous diagnosis despite multiple tests and evaluations is also supportive of neurogenic TOS. Although numbness and tingling in the hand are often considered worrisome symptoms, pain is the most disabling and predominant symptom for which treatment is directed. The findings on examination that support neurogenic TOS include localized muscle spasm and tenderness over the left scalene triangle and pectoralis minor tendon, with reproduction of hand symptoms on palpation. Although positional ablation of the radial pulse suggests compression of the subclavian artery within the scalene triangle, this is a common finding even in asymptomatic individuals; the positional pulse examination therefore offers little insight into the nature or cause of the symptoms. The most important finding is difficulty completing the EAST: a positive test is highly suggestive of neurogenic TOS, whereas a negative result calls the diagnosis into question.

Neurogenic TOS is thought to arise as a result of variations in individual anatomy that predispose to neurovascular compression, combined with some form of trauma to the scalene and/or pectoralis minor muscles. One of the anatomical factors associated with TOS is the presence of a congenital cervical rib. Radiographs should be inspected to evaluate whether such an anomaly is present, because it may help to solidify the diagnosis and influence management decisions.

Radiographs

Radiology Report

Normal radiographs of the upper chest and cervical spine, with no evidence of cervical rib.

Discussion

In some cases where TOS is suspected, one must consider the possibility of subclavian artery compression resulting in formation of a poststenotic subclavian aneurysm. These lesions are usually clinically silent until they produce thromboembolism with occlusion of distal vessels within the upper extremity. Because the clinical presentation of this complication may be subtle, the examiner must be sure that any changes in perfusion of the hand do not represent ischemia. When physical examination is equivocal or in cases where a cervical rib is present, it is useful to consider magnetic resonance (MR) angiography as a noninvasive test by which to rule out the presence of a subclavian aneurysm.

Magnetic Resonance Angiography

MRA Report

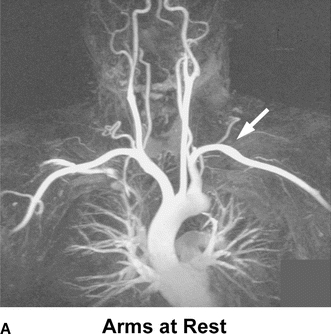

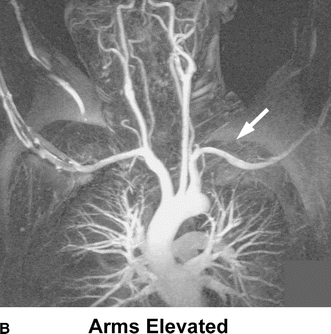

A contrast-enhanced MR angiogram was performed to evaluate the left subclavian artery (arrow) at the level of the thoracic outlet. With the arms at rest, the subclavian arteries exhibit a normal contour and luminal caliber, without signs of occlusive disease or aneurysm dilatation (Fig. 1A). With the arms elevated above the head, the subclavian arteries remain patent without signs of positional occlusion (Fig. 1B). The results of this study are normal.

FIGURE 1 A: A contrast-enhanced MR angiogram was performed to evaluate the left subclavian artery (arrow) at the level of the thoracic outlet. With the arms at rest, the subclavian arteries exhibit a normal contour and luminal caliber, without signs of occlusive disease or aneurysm dilatation. B: With the arms elevated above the head, the subclavian arteries remain patent without signs of positional occlusion.

Recommendation

A trial of physical therapy specifically targeted toward relief of neurogenic TOS is recommended. Although the patient has not improved with previous courses of therapy, it is unlikely that these efforts were undertaken with the specific diagnosis of TOS. Because therapy for TOS differs from that given for other related conditions, this treatment should be conducted by a therapist with expertise, interest, and experience in management of TOS. Adjunctive measures should be recommended, including use of anti-inflammatory medications and muscle relaxants. Use of narcotic pain medications is not recommended.

Case Continued

After 8 weeks of physical therapy, the patient has had no change in symptoms. The therapist reports that the patient has made minimal improvement in pain-free range of motion and that her progress is limited by ongoing pain with activity. At this point, she returns to clinic to consider evaluation for surgical intervention. Following the visit, she undergoes an anterior scalene and pectoralis minor muscle block with local anesthetic under imaging guidance, which results in complete relief of symptoms for several hours.

Diagnosis and Recommendation

This patient may be considered to have neurogenic TOS refractory to conservative treatment, and surgical decompression is recommended. The patient is informed that a substantial improvement in symptoms can be expected in approximately 85% to 90% of patients following appropriate surgical treatment but that complete long-term relief of all symptoms (i.e., “cure”) is unlikely. It is emphasized that ongoing physical therapy and rehabilitation will remain an essential part of her overall treatment. Potential complications of surgery are discussed, including nerve or vascular injuries and temporary dysfunction of the phrenic and/or long thoracic nerves, with an incidence in experienced hands of less than 2%. The positive response to the localized muscle block is a very strong predictor of symptom relief following surgery.

Surgical Approach

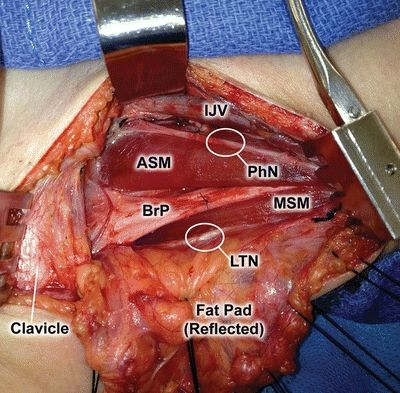

The patient has compression in both the supraclavicular space and the infraclavicular subcoracoid space requiring surgical decompression in both areas. The recommended approach to this problem is supraclavicular exploration with complete resection of the anterior and middle scalene muscles, first rib resection, and brachial plexus neurolysis, along with pectoralis minor tenotomy. During dissection and resection of the anterior scalene muscle, care is taken to identify and preserve the phrenic nerve, brachial plexus nerve roots C5-T1, and the subclavian artery. Similarly, during dissection and resection of the middle scalene muscle, one must identify and preserve the long thoracic nerve as well as the brachial plexus (Fig. 2). Any associated fibrous bands and muscle anomalies within the scalene triangle are also resected. Complete brachial plexus neurolysis is included to remove any associated fibroinflammatory tissue that may be contributing to nerve irritation. It is recommended that first rib resection be included in most decompression procedures, although some specialists avoid resection of the first rib if they believe that adequate decompression has been accomplished by scalenectomy alone. The first rib is resected posteriorly to its junction with the C7 transverse process, with clear visualization and protection of the C8 and T1 nerve roots, and anteriorly to a level just medial to the scalene tubercle, underneath the clavicle. Following supraclavicular decompression, the brachial plexus nerve roots are wrapped with an absorbable polymeric film in an effort to reduce postoperative adhesions. A closed-suction drain is placed into the pleural space and is removed several days later. Two small multihole perfusion catheters are placed within the resection bed and connected to an osmotic pump, which will provide continuous infusion of local anesthetic for the first three postoperative days.

FIGURE 2 Sample operative image of the critical view of the essential structures in a standard supraclavicular thoracic outlet decompression. IJV, internal jugular vein; ASM, anterior scalene muscle; PhN, phrenic nerve; BrP, Brachial plexus; MSM, middle scalene muscle; LTN, long thoracic nerve.