22 Myocarditis

Etiology and Pathogenesis

In North America and Europe, the majority of cases of myocarditis probably result from viral infection. Many viruses have been associated with myocarditis (Box 22-1). Initial serologic studies suggested that enteroviruses, such as coxsackie B, are common causes of viral myocarditis. However, the application of direct molecular techniques to endomyocardial biopsy specimens, and perhaps changing epidemiology, has led to increasing recognition of adenoviruses, parvovirus, and hepatitis C as etiologic agents. In HIV infection, there is often evidence of myocarditis when cardiac decompensation occurs, although it is unclear whether HIV or opportunistic infections are responsible.

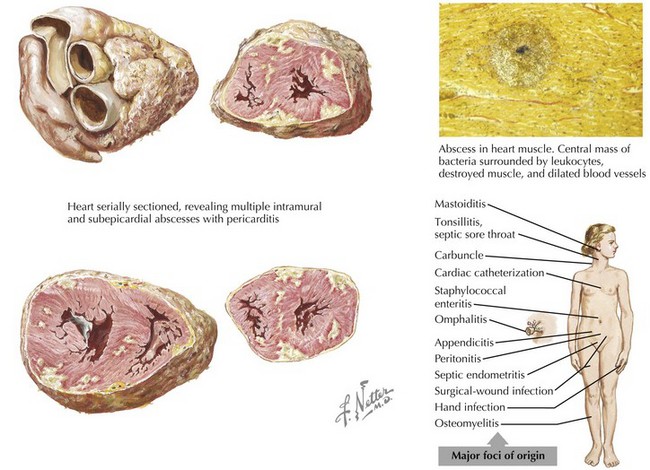

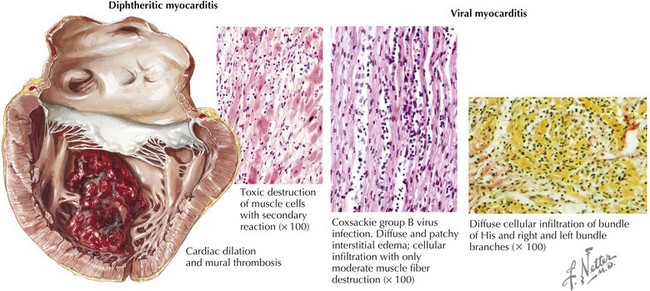

Rarely, bacterial infections, through spread from endogenous sources (Fig. 22-1), can produce focal or diffuse myopericarditis. One of the earliest recognized causes of myocarditis was diphtheria. Up to 20% of diphtheria patients have cardiac involvement, and myocarditis is the leading cause of death with this infection. The toxin produced by the diphtheria bacillus injures myocardial cells (Fig. 22-2). In South and Central America, the most common cause of infectious myocarditis is the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi—the causative agent of Chagas’ disease.

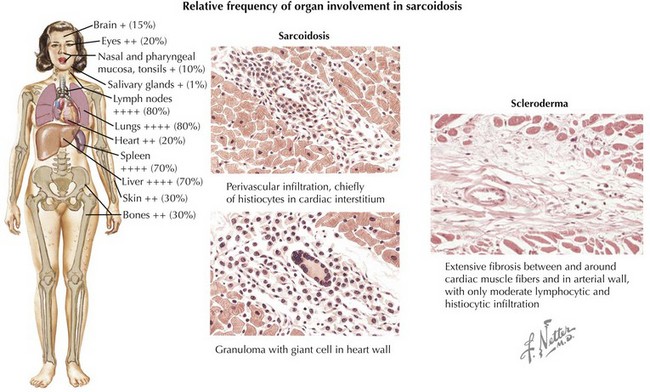

Sarcoidosis, a systemic granulomatous disorder of unknown etiology, involves the myocardium in at least 20% of cases. Cardiac involvement ranges from a few scattered lesions to extensive involvement (Fig. 22-3). As a result, endomyocardial biopsy may be diagnostic but is frequently unreliable in confirming myocarditis. Giant cell myocarditis is a rare but highly lethal form of myocarditis of suspected immune or autoimmune etiology that may be associated with other inflammatory conditions such as Crohn’s disease. Although the cumulative studies on immunosuppressive therapy for myocarditis are not positive (see below), the above causes of myocarditis do often respond to immunosuppression. Peripartum cardiomyopathy has been associated with a greater than 50% rate of myocarditis on endomyocardial biopsy, although the etiology remains unknown.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree