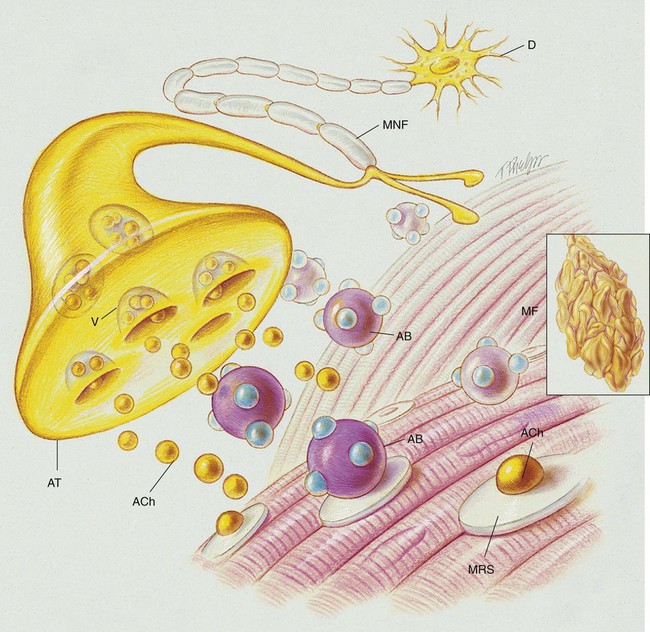

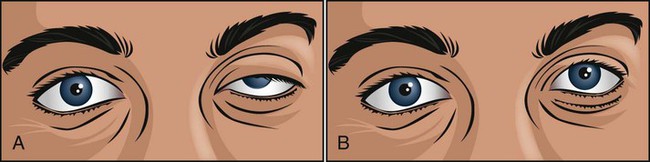

After reading this chapter, will be able to: • List the anatomic alterations of the lungs associated with myasthenia gravis. • Describe the causes of myasthenia gravis. • List the cardiopulmonary clinical manifestations associated with myasthenia gravis. • Describe the general management of myasthenia gravis. • Describe the clinical strategies and rationales of the SOAPs presented in the case study. • Define key terms and complete self-assesment questions at the end of the chapter and on Evolve. Myasthenia gravis is a chronic disorder of the neuromuscular junction that interferes with the chemical transmission of acetylcholine (ACh) between the axonal terminal and the receptor sites of voluntary muscles (see Figure 29-1). It is characterized by fatigue and weakness, with improvement following rest. Because the disorder affects only the myoneural (motor) junction, sensory function is not lost. The cause of myasthenia gravis appears to be related to ACh receptor antibodies (the IgG antibodies) that block the nerve impulse transmissions at the neuromuscular junction. It is believed that the IgG antibodies disrupt the chemical transmission of ACh at the neuromuscular junction by (1) blocking the ACh from the receptor sites of the muscular cell, (2) accelerating the breakdown of ACh, and (3) destroying the receptor sites (see Figure 29-1). Receptor-binding antibodies are present in 85% to 90% of persons with myasthenia gravis. Although the specific events that activate the formation of the antibodies remain unclear, the thymus gland is almost always abnormal; it is generally presumed that the antibodies arise within the thymus or in related tissue. The ice pack test (Figure 29-2) is a very simple, safe, and reliable procedure for diagnosing myasthenia gravis in patients who have ptosis (droopy eye). In addition, the ice pack test does not require special medications or expensive equipment and is free of adverse effects. The test consists of the application of an ice pack to the patient’s symptomatic eye for 3 to 5 minutes. The test is considered positive for myasthenia gravis when there is improvement of the ptosis (an increase of at least 2 mm in the palpebral fissure from before to after the test).

Myasthenia Gravis

Anatomic Alterations of the Lungs Associated with Myasthenia Gravis

Etiology and Epidemiology

Screening and Diagnosis

Ice Pack Test

Myasthenia Gravis