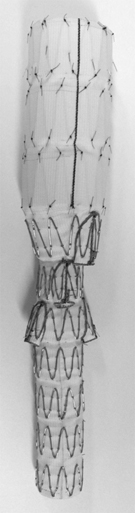

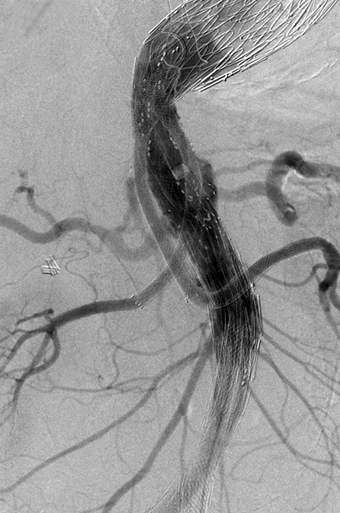

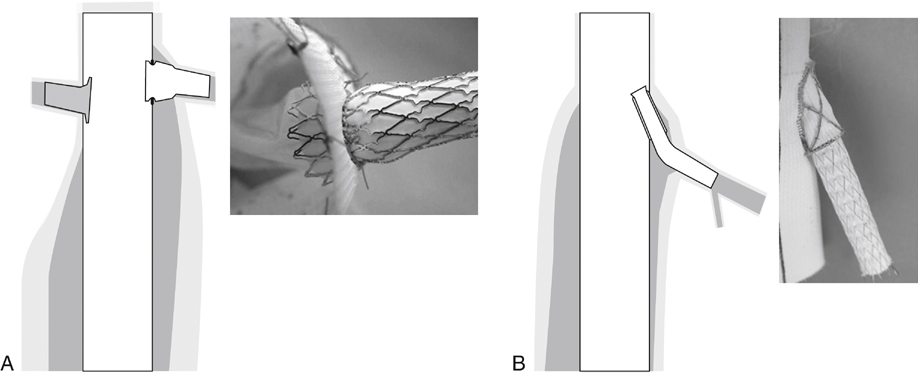

There are two basic types of branch attachment site: fenestrations and cuffs. A fenestration is merely a reinforced hole in the wall of the trunk (Figure 1A), whereas a cuff is a short branch of the stent graft, extending up, down, or around the trunk (Figure 1B). Cuff-based and fenestration-based stent grafts have several fundamental similarities. For example, both involve inserting a bridging catheter through the attachment site and across the aneurysm cavity into the target artery, followed by inserting a bridging covered stent. There are also fundamental differences. For example, most fenestration-based branches are inserted transfemorally, whereas most cuff-based branches are inserted transbrachially; most fenestration-based branches are balloon expanded, whereas most cuff-based branches are self-expanding; and most fenestration-based branches are inserted while the stent graft is held (by a constraining wire) in a partially expanded state, whereas most cuff-based branches are inserted once the stent graft is fully deployed. The deployment of a fenestration-based branch has much in common with the deployment of a typical fenestration, which is a procedure familiar to many outside the United States, where fenestrated stent grafts have long been commercially available. The standard premade thoracoabdominal stent graft (Figure 2) is combined with a variety of premade proximal and distal extensions, some specific to TAAA repair, others commercially available for the treatment of thoracic aortic aneurysms (TAA) and dissection. Minor disparities between distribution of cuffs on the stent graft and the distribution of branches on the aorta can be accommodated by variation in branch morphology. The exceptions are usually cases of type II and type III TAAA, in which the dilating visceral aorta has also lengthened, taking its branches in different directions. The original off-the-shelf TAAA component has a 22-Fr delivery sheath; the current low-profile version has an 18-Fr delivery sheath. This, combined with low-profile versions of TX-2 thoracic stent grafts, has greatly reduced the need for iliofemoral bypass, especially in women. Stent graft selection and design are usually based on three-dimensional reconstructions of high-resolution (1- to 2-mm slices) computed tomography angiography (CTA), showing the positions of the implantation sites and the aortic branches relative to the proximal margin of the celiac artery. Branch artery orientation is usually assigned a position relative to a clock face, with anterior, posterior, left, and right represented by 12:00, 6:00, 3:00, and 9:00, respectively. Small amounts (1 to 2 hours, or 30 to 60 degrees) of cuff-to-artery misalignment are generally well tolerated by cuff-based branches but not by fenestrations. More severe misalignment is an obstacle to branch insertion, but not an insuperable one (Figure 3). Similarly, the distance from the cuff to the target artery can range from 10 to 40 mm without significant effects on branch deployment, patency, or stability.

Multibranched Endovascular Repair of Thoracoabdominal Aortic Aneurysm

Multibranched Thoracoabdominal Stent Grafts

Standard Stent Graft

Planning The Repair

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Thoracic Key

Fastest Thoracic Insight Engine