Electrocardiographic bundle branch block (BBB) has higher cardiac and all-cause death. However, reports on the association between BBBs and mortality in the general populations are conflicting. The aim of this study was to evaluate the risk for coronary heart disease (CHD) and all-cause death associated with left BBB (LBBB) and right BBB (RBBB) during 14 years of follow-up in 66,450 participants from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study. Cox proportional-hazards regression was performed for mortality risk in Women with LBBB (n = 714) and those with RBBB (n = 832). In risk models adjusted for demographic and clinical risk factors in women with cardiovascular disease (CVD), hazard ratios for CHD death were 2.92 (95% confidence interval 2.08 to 4.08, p <0.001) for LBBB and 1.62 (95% confidence interval 1.08 to 2.43, p <0.05) for RBBB, and only LBBB was a significant predictor of all-cause death (hazard ratio 1.43, 95% confidence interval 1.11 to 1.83, p <0.01). In CVD-free women, only LBBB was a significant predictor of CHD death (fully adjusted hazard ratio 2.17, 95% confidence interval 1.37 to 3.43, p <0.01), and neither blocks was predictive of all-cause death. From several repolarization variables that were significant mortality predictors in univariate risk models, after adjustment for other electrocardiographic covariates and risk factors, ST J-point depression in lead aVL ≤−30 μV in women with LBBB was an independent predictor of CHD death, with a more than fivefold increase in risk. None of the repolarization variables were independent predictors in women with RBBB. In conclusion, prevalent LBBB in CVD-free women and LBBB and RBBB in women with CVD were significant predictors of CHD death. In women with LBBB, ST J-point depression in lead aVL was a strong independent predictor of CHD death.

The presence of electrocardiographic (ECG) depolarization and repolarization abnormalities has been shown to provide valuable independent information on the risk for coronary heart disease (CHD) and all-cause death. Earlier reports from community-based population studies found no or only marginal risk for right bundle branch block (RBBB). The results for left bundle branch block (LBBB) have also been conflicting, with some studies reporting a significant increase in mortality, while other studies have not found LBBB to be a significant predictor. The objectives of the present analysis were (1) to evaluate CHD and all-cause death risk associated with RBBB and LBBB in subgroups of women with and without cardiovascular disease (CVD) at baseline and (2) to evaluate if repolarization abnormalities in women with RBBB and LBBB provide additional prognostic information.

Methods

The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) clinical trial is a multicenter study of risk factors for the prevention of common causes of mortality, morbidity, and impaired quality of life in United States postmenopausal women. Detailed eligibility criteria and details on recruitment methods, randomization, follow-up, data and safety monitoring, and quality assurance have been published previously. The study was approved by each study site’s institutional review board. All participants provided written informed consent.

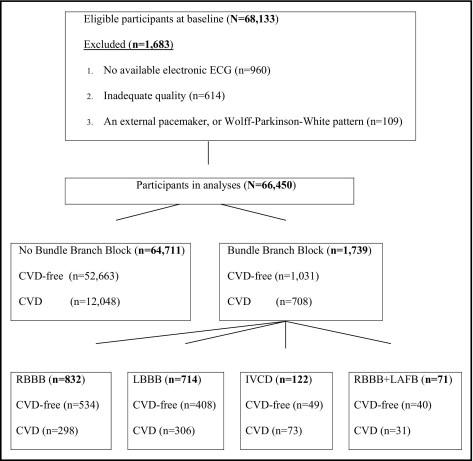

Of the 68,133 WHI clinical trial participants who were enrolled from 1993 to 1998, we excluded 1,683 participants from analyses: 960 with no ECG data, 614 with inadequate quality electrocardiograms, and 109 with external pacemakers or Wolff-Parkinson-White pattern. The remaining 66,450 participants at baseline were stratified into subgroups according to ECG criteria and clinical status at baseline ( Figure 1 ) : (1) CVD-free women with no bundle branch block (BBB; QRS duration <120 ms, n = 52,663); (2) women with CVD and no BBB (n = 12,048); (3) women with RBBB (n = 832), 534 among CVD-free women and 298 among women with CVD; (4) women with LBBB (n = 714), 408 among CVD-free women and 306 among women with CVD; (5) women with indeterminate types of intraventricular conduction defects (n = 122), 49 among CVD-free women and 73 among women with CVD; and (6) women with a combination of RBBB and left anterior fascicular block (n = 71), 40 among CVD-free women and 31 among women with CVD. The CVD group was identified by the presence of ECG evidence of myocardial infarction by the Minnesota Code or Novacode at baseline or a history of myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, coronary artery bypass surgery, coronary angioplasty, or congestive heart failure.

Outcomes considered in the present investigation were CHD death and all-cause mortality that occurred from baseline through September 24, 2010. The follow-up time was up to 17 years (mean 14.2). After baseline, deaths and hospitalization events were ascertained in each clinical center by annual follow-up calls, review of vital records, and community surveillance of hospitalized and fatal events. Detailed definitions for criteria for CHD death classification were previously published. Briefly, CHD deaths included women who died from no known non-CHD cause and either a history of chest pain within 72 hours before death or a history of chronic ischemic heart disease in the absence of valvular heart disease.

Identical electrocardiographs (MAC PC; GE Marquette Electronics, Inc., Milwaukee, Wisconsin) were used at all clinic sites, and rest, 10-second standard simultaneous 12-lead electrocardiograms were recorded in all participants using strictly standardized procedures. All electrocardiograms for the present study were analyzed using the 2001 version of the GE Marquette 12-SL program (GE Marquette Electronics, Inc.) in a central electrocardiography laboratory, the Epidemiological Cardiology Research Center at the Wake Forest School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, North Carolina), where they were visually inspected for technical errors and inadequate quality. QRS duration was determined between the earliest onset and the latest end of the QRS complex from the vector magnitude curve derived from standard 12 lead electrocardiograms. BBBs were classified according to the Minnesota Code criteria for complete LBBB (Minnesota Code 7.1), complete RBBB (Minnesota Code 7.2), intraventricular conduction defect (Minnesota Code 7.4), and the combination of RBBB and left anterior fascicular block (Minnesota Code 7.8). Spatial QRS-T angle was derived as the angle between the mean QRS and T vectors.

Frequency distributions of ECG variables were first inspected to rule out anomalies and outliers possibly due to measurement artifacts. Descriptive statistics were used to determine mean values, standard deviations, and percentile distributions for continuous variables and frequencies and percentiles for categorical variables. Cox proportional-hazards regression was used to assess the associations of ECG variables with the risk for CHD death and total mortality using univariate and multivariate risk models with adjustment for demographic and clinical factors (age, ethnicity, body mass index, smoking status, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, previous stroke, history of CVD, hypercholesterolemia, family history of CHD, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, and study component/arm in hormone therapy/dietary modification/calcium and vitamin D trial participants). Age was used as the time scale, and birth cohort was used as a stratification factor in all analyses. Predictor ECG parameters were first evaluated as continuous variables and then stratified into quintiles. Quintiles 2 to 4 were first used as the reference group with hazard ratio (HR) = 1 and evaluating the risk for the lowest and the highest quintiles. No U-shaped risk profiles were observed, and subsequently the risk associated with the highest quintile or the lowest quintile was evaluated using the remaining quintiles as the reference group. SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina) was used in all analysis.

Results

This analysis included 66,450 women (average age 63 years), of whom 82% were non-Hispanic white, 10% were African American, 34% had hypertension, 6.3% had diabetes, and 19% had histories of CVD or the presence of ECG evidence of myocardial infarction. BBB was present in 2.6% of the participants (714 with LBBB, 832 with RBBB, 122 with intraventricular conduction defects, and 71 with RBBB plus left anterior fascicular block). Details on the demographic, ECG, and clinical characteristics of the study population are listed in Table 1 . During an average 14 years of follow-up, 316 participants (18%) with BBB died, and 136 (8%) had fatal CHD events. The HRs and 95% confidence intervals for CHD death for BBB are listed in Table 2 . In a multivariate model adjusted for demographic and clinical factors, the HR in CHD-free women remained significant (more than twofold) for LBBB but not for RBBB. In women with CVD, the risk for CHD death was nearly threefold for LBBB, and it remained significant also for RBBB with a 62% increased risk. For intraventricular conduction defect or RBBB combined with left anterior fascicular block, the risk was increased approximately threefold.

| Variable | No BBB | RBBB | LBBB | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVD Free (n = 52,663) | CVD (n = 12,048) | CVD Free (n = 534) | CVD (n = 298) | CVD Free (n = 408) | CVD (n = 306) | |

| Age (years) | 62 ± 6.9 | 65 ± 7.0 ‡ | 65 ± 6.8 | 67 ± 6.9 † | 66 ± 6.9 | 67 ± 6.8 |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) | 29 ± 5.8 | 30 ± 6.2 ‡ | 29 ± 5.7 | 31 ± 6.2 † | 29 ± 5.7 | 29 ± 5.5 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 127 ± 17.1 | 131 ± 18.1 ‡ | 132 ± 19.7 | 135 ± 18.8 † | 134 ± 17.6 | 134 ± 18.4 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 76 ± 9.0 | 75 ± 9.4 ‡ | 76 ± 9.2 | 75 ± 9.6 | 77 ± 9.6 | 75 ± 9.4 † |

| Non-Hispanic white | 81.7% | 80.6% | 83.0% | 80.2% | 88.7% | 88.6% |

| African American | 9.7% | 12.3% ⁎ | 8.1% | 12.8% | 6.1% | 8.5% |

| Current smoking | 7.9% | 8.2% † | 6.6% | 7.5% | 5.7% | 6.0% |

| Hypertension | 30.2% | 49.7% ‡ | 35.7% | 57.7% ‡ | 41.7% | 60.9% ‡ |

| Diabetes | 5.2% | 10.7% ‡ | 6.4% | 18.8% ‡ | 5.4% | 11.1% † |

| Hypercholesterolemia § | 10.8% | 20.8% ‡ | 12.6% | 22.1% † | 13.2% | 16.6% |

| Previous stroke | 0% | 5.8% ‡ | 0% | 4.7% ‡ | 0% | 3.9% ‡ |

| Family history of CHD | 17.4% | 24.5% ‡ | 17.0% | 25.9% † | 16.2% | 29.4% ‡ |

| CHD death | 1.7% | 5.0% ‡ | 3.9% | 9.1% † | 5.9% | 15.7% ‡ |

| All-cause death | 9.3% | 16.5% ‡ | 12.4% | 22.5% † | 15.7% | 26.5% † |

| ECG characteristics | ||||||

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 66 ± 9.9 | 66 ± 10.7 | 67 ± 9.8 | 67 ± 10.5 | 68 ± 10.0 | 67 ± 9.9 |

| QRS duration (ms) | 86 ± 8.3 | 87 ± 9.1 ‡ | 136 ± 10.6 | 136 ± 11.3 | 140 ± 10.5 | 143 ± 11.9 † |

| QRS axis (°) | 23 ± 29.3 | 18 ± 31.1 ‡ | 22 ± 47.6 | 11 ± 52.1 † | −16 ± 28.7 | −12 ± 34.6 |

| T-wave axis (°) | 40 ± 22.6 | 43 ± 33.6 ‡ | 26 ± 23.0 | 30 ± 36.9 ⁎ | 90 ± 47.6 | 98 ± 61.8 ⁎ |

| Spatial QRS-T angle (°) | 45 ± 23.5 | 53 ± 30.9 ‡ | 82 ± 29.2 | 87 ± 34.9 † | 134 ± 19.2 | 138 ± 21.3 ⁎ |

| ST J-point amplitude (μV) | ||||||

| Lead aVL | 8 ± 24.0 | 6 ± 26.2 ‡ | −4 ± 20.1 | −11 ± 25.3 ‡ | −6 ± 27.3 | −7 ± 33.2 |

| Lead aVR | −18 ± 20.5 | −13 ± 23.1 ‡ | −12 ± 20.1 | —5 ± 25.5 ‡ | 9 ± 23.2 | 17 ± 29.8 † |

| Lead V 1 | −2 ± 25.6 | 1 ± 29.6 ‡ | 31 ± 31.0 | 34 ± 32.5 | 103 ± 47.6 | 105 ± 59.5 |

| Lead V 6 | 15 ± 22.9 | 9 ± 26.9 ‡ | 7 ± 22.3 | 0 ± 28.3 ‡ | −14 ± 30.1 | −21 ± 38.7 † |

| T-wave amplitude (μV) | ||||||

| Lead aVL | 86 ± 86.6 | 69 ± 102.0 ‡ | 167 ± 100.4 | 134 ± 127.3 ‡ | −125 ± 124.3 | −119 ± 125.6 |

| Lead aVR | −228 ± 86.4 | −197 ± 103.5 ‡ | −265 ± 86.2 | —227 ± 99.9 ‡ | −72 ± 137.6 | −47 ± 142.9 ⁎ |

| Lead V 1 | −14 ± 113.7 | −4 ± 126.5 ‡ | −223 ± 120.0 | −201 ± 132.8 † | 390 ± 172.4 | 390 ± 187.4 |

| Lead V 6 | 226 ± 116.8 | 188 ± 138.5 ‡ | 285 ± 120.1 | 241 ± 149.5 ‡ | −24 ± 178.7 | −47 ± 194.8 |

‡ p <0.001 between the CVD and CVD-free in the groups with No-BBB, RBBB, or LBBB, separately.

| Category | Event Rate | Univariate HR (95% CI) | Multivariate HR (95% CI) ⁎ |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHD death: CVD free at baseline | |||

| No BBB | 894/52,663 (1.7%) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| LBBB | 24/408 (5.9%) | 2.40 (1.60–3.61) § | 2.17 (1.37–3.43) ‡ |

| RBBB | 21/534 (3.9%) | 1.68 (1.09–2.59) † | 1.31 (0.77–2.23) ∥ |

| CHD death: CVD at baseline | |||

| No BBB | 597/12,048 (5.0%) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| LBBB | 48/306 (15.7%) | 2.85 (2.12–3.82) § | 2.92 (2.08–4.08) § |

| RBBB | 27/298 (9.1%) | 1.60 (1.09–2.36) † | 1.62 (1.08–2.43) † |

| IVCD | 10/73 (13.7%) | 2.72 (1.46–5.08) ‡ | 2.52 (1.34–4.75) ‡ |

| RBBB and LAFB | 5/31 (16.1%) | 2.87 (1.19–6.92) † | 3.09 (1.26–7.58) † |

| All-cause death: CVD free at baseline | |||

| No BBB | 4,884/52,663 (9.3%) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| LBBB | 64/408 (15.7%) | 1.25 (0.98–1.60) ∥ | 1.18 (0.90–1.55) ∥ |

| RBBB | 66/534 (12.4%) | 1.02 (0.80–1.30) ∥ | 0.89 (0.67–1.19) ∥ |

| IVCD | 3/49 (6.1%) | 0.52 (0.17–1.61) ∥ | 0.44 (0.11–1.75) ∥ |

| RBBB and LAFB | 6/40 (15.0%) | 1.04 (0.47–2.31) ∥ | 0.91 (0.38–2.18) ∥ |

| All-cause death: CVD at baseline | |||

| No BBB | 1,983/12,048 (16.5%) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| LBBB | 81/306 (26.5%) | 1.44 (1.15–1.80) † | 1.43 (1.11–1.83) † |

| RBBB | 67/298 (22.5%) | 1.19 (0.93–1.51) ∥ | 1.10 (0.84–1.44) ∥ |

| IVCD | 16/73 (21.9%) | 1.31 (0.80–2.14) ∥ | 1.19 (0.72–1.99) ∥ |

| RBBB and LAFB | 13/31 (41.9%) | 2.23 (1.30–3.85) † | 2.69 (1.55–4.67) † |

⁎ Multivariate risk model adjusted for key demographic and clinical variables of age, ethnicity, body mass index, smoking status, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, previous stroke, history of cardiovascular disease, hypercholesterolemia, family history of coronary heart disease, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, ECG left ventricular hypertrophy (identified by [R-wave amplitude in lead aVL + S-wave amplitude in lead V 3 ] ≥2,200 μV for electrocardiograms with QRS duration <120 ms), and study component/arm groups (hormone therapy/dietary modification/calcium and vitamin D).

HRs for CHD death in women with BBB are listed in Table 3 for QRS duration, spatial QRS-T angle, and ST J-point and T-wave amplitudes in leads aVR, aVL, V 1 , and V 6 for the combined group of women with and without CVD for a univariate risk model and for 2 multivariate risk models. ECG variables with significant HRs in the univariate risk model were entered simultaneously into multivariate model 1 and individually adjusted for the other ECG variables to identify significant independent predictor variables and were also entered simultaneously into multivariate model 2 with an additional adjustment for demographic and clinical risk factors listed in the footnote of Table 2 . Because QRS duration was not a significant predictor of CHD death for either LBBB or RBBB, it was removed from multivariate models. QRS-T angle was among the several ECG variables that in the univariate model were significant predictors of CHD death in women with RBBB and LBBB but were removed as nonsignificant from multivariate models. None of the repolarization-associated ECG variables in RBBB remained significant predictors of CHD death in multivariate models. In contrast, for LBBB in the combined group of women with and without CVD, ST J-point depression ≤−30 μV in lead aVL remained a significant predictor of CHD death (HR 5.58, 95% confidence interval 2.79 to 11.2, p <0.001), and deep negative T-waves in lead V 6 (≤−170 μV) or elevated ST J-point in lead aVR (≥30 μV) was associated with a double increase in risk. Of note is the fact that these pronounced increases in the risk for CHD death were observed in a relatively large group of women (20%, the lowest quintile of each variable, with quintiles 2 to 5 as the reference group, except for leads V 1 and aVR using the highest quintile with quintiles 1 to 4 as the reference group).

| Reference Quintiles | Test Quintile Threshold | Univariate | Multivariate Model 1 ⁎ | Multivariate Model 2 † | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LBBB (72/714 [10.1%]) | |||||

| QRS duration (ms) | Q1–Q4 | >150 (Q5) | 1.66 (0.98–2.82) ¶ | Removed | — |

| QRS-T angle (°) | Q1–Q4 | ≥153 (Q5) | 2.30 (1.42–3.75) § | 1.11 (0.61–2.03) ¶ | 0.61 (0.29–1.31) ¶ |

| ST J-point amplitude (μV) | |||||

| Lead aVL | Q2–Q5 | ≤−30 (Q1) | 3.80 (2.37–6.07) ∥ | 2.80 (1.68–4.68) ∥ | 5.58 (2.79–11.2) ∥ |

| Lead aVR | Q1–Q4 | ≥30 (Q5) | 3.08 (1.92–4.94) ∥ | 1.70 (0.88–3.30) ¶ | 2.33 (1.06–5.12) ‡ |

| Lead V 1 | Q1–Q4 | ≥141 (Q5) | 2.01 (1.23–3.29) § | 1.11 (0.64–1.93) ¶ | 0.67 (0.32–1.38) ¶ |

| Lead V 6 | Q2–Q5 | ≤−44 (Q1) | 2.82 (1.75–4.53) ∥ | 1.16 (0.59–2.26) ¶ | 1.18 (0.53–2.61) ¶ |

| T-wave amplitude (μV) | |||||

| Lead aVL | Q2–Q5 | ≤−219 (Q1) | 1.08 (0.62–1.88) ¶ | Removed | — |

| Lead aVR | Q1–Q4 | ≥80 (Q5) | 1.94 (1.17–3.20) ‡ | 0.62 (0.32–1.23) ¶ | 0.56 (0.25–1.26) ¶ |

| Lead V 1 | Q1–Q4 | ≥532 (Q5) | 1.41 (0.83–2.38) ¶ | Removed | — |

| Lead V 6 | Q2–Q5 | ≤−170 (Q1) | 3.04 (1.90–4.86) ∥ | 2.11 (1.09–4.05) ‡ | 2.34 (1.04–5.26) ‡ |

| RBBB (48/832 [5.8%]) | |||||

| QRS duration (ms) | Q1–Q4 | >145 (Q5) | 1.80 (0.97–3.36) ¶ | Removed | — |

| QRS-T angle (°) | Q1–Q4 | ≥110 (Q5) | 2.27 (1.26–4.11) § | 1.72 (0.91–3.26) ¶ | 1.38 (0.62–3.05) ¶ |

| ST J-point amplitude (μV) | |||||

| Lead aVL | Q2–Q5 | ≤−25 (Q1) | 1.27 (0.66–2.45) ¶ | Removed | — |

| Lead aVR | Q1–Q4 | ≥5 (Q5) | 1.78 (0.97–3.25) ¶ | Removed | — |

| Lead V 1 | Q1–Q4 | >53 (Q5) | 1.85 (1.02–3.38) ‡ | 1.46 (0.78–2.74) ¶ | 2.07 (0.93–4.61) ¶ |

| Lead V 6 | Q2–Q5 | ≤−15 (Q1) | 1.36 (0.73–2.55) ¶ | Removed | — |

| T-wave amplitude (μV) | |||||

| Lead aVL | Q2–Q5 | ≤78 (Q1) | 2.53 (1.40–4.58) § | 1.57 (0.80–3.08) ¶ | 1.80 (0.78–4.15) ¶ |

| Lead aVR | Q1–Q4 | ≥−180 (Q5) | 2.42 (1.35–4.34) § | 1.27 (0.55–2.96) ¶ | 1.47 (0.51–4.30) ¶ |

| Lead V 1 | Q1–Q4 | ≥−141 (Q5) | 2.36 (1.30–4.26) § | 1.60 (0.83–3.08) ¶ | 1.44 (0.67–3.11) ¶ |

| Lead V 6 | Q2–Q5 | ≤170 (Q1) | 2.43 (1.35–4.36) ‡ | 1.32 (0.57–3.03) ¶ | 0.76 (0.24–2.43) ¶ |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree