36 Mitral Valve Disease

Etiology and Pathogenesis

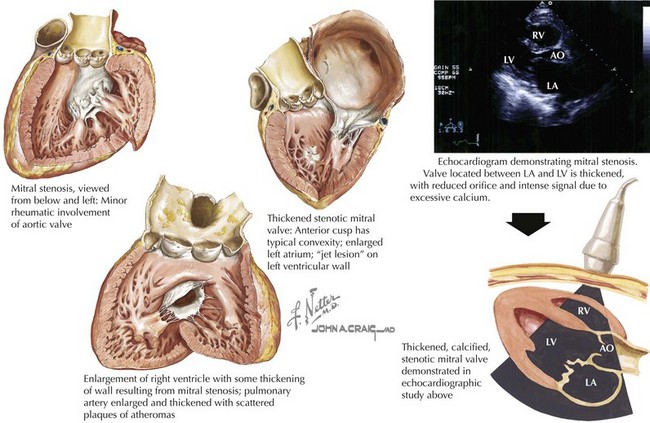

Mitral Stenosis

The normal mitral valve cross-sectional area in diastole is 4 to 6 cm2. Blood flow is impaired when the valve orifice is narrowed to less than 2 cm2, creating a pressure gradient with exertion. A valve area smaller than 1 cm2 is considered critical mitral stenosis and results in a significant pressure gradient across the valve at rest with chronically increased left atrial (LA) pressures (Fig. 36-1).

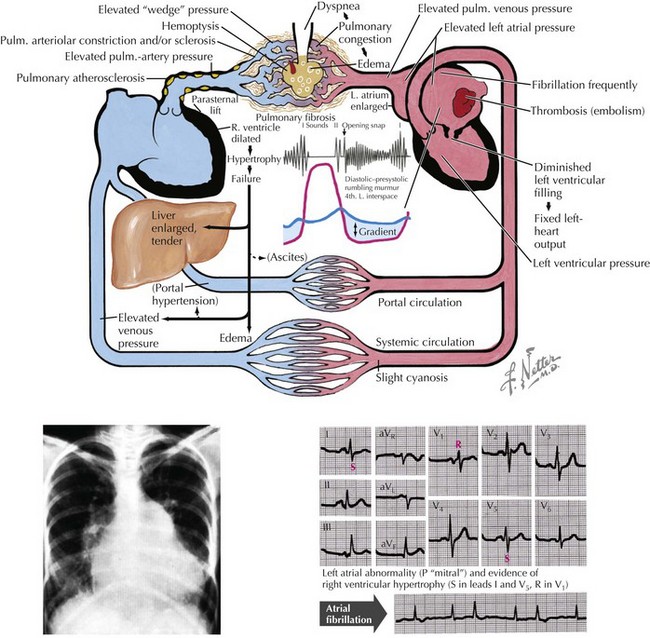

The hemodynamic effects of chronic mitral stenosis include pulmonary venous and arterial hypertension; right ventricular (RV) hypertrophy, dilation, and failure; peripheral edema; tricuspid regurgitation; ascites; and hepatic injury with cirrhosis (Fig. 36-2).

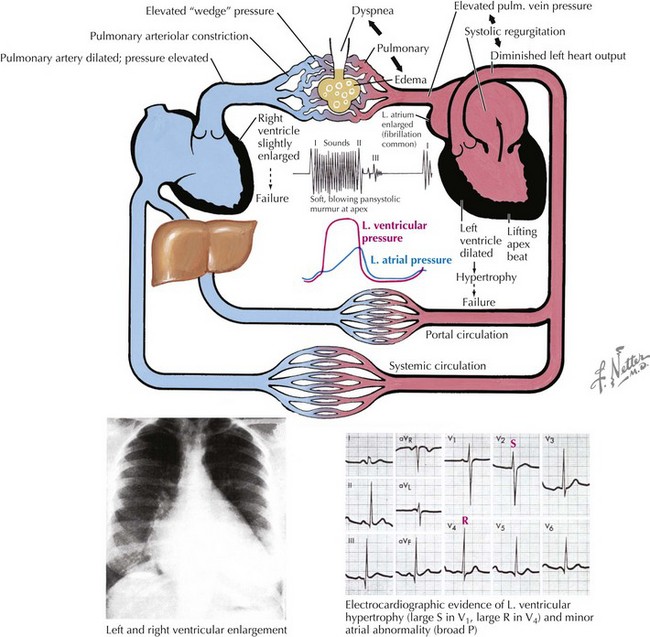

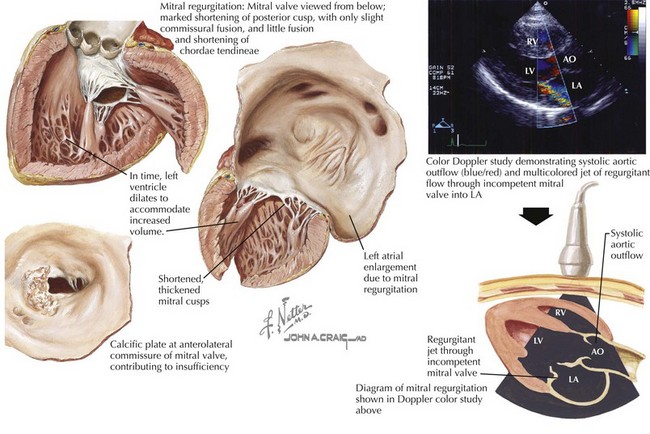

Mitral Regurgitation

With mitral regurgitation, blood is discharged during systole into the left atrium in addition to traveling its usual route through the aortic valve and into the aorta. If the regurgitant volume is large, LA remodeling occurs with dilation to accommodate increased volumes without intolerable LA hypertension (Fig. 36-3). Over time, as an increasing fraction of ventricular volume is regurgitant, the “forward” ventricular output is reduced, and symptoms and other findings of mitral regurgitation become obvious (Fig. 36-4). Patients are generally clinically well if the regurgitant fraction (regurgitant volume/total ejection volume) is less than 0.4. Patients with regurgitant fractions greater than 0.5 predictably develop left ventricular (LV) failure and have high morbidity and mortality. Any evidence of LV failure (LV ejection fraction <60%) is also a critical marker of poor prognosis.

Figure 36-3 Mitral regurgitation.

AO, aorta; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle.