General

Metastasis to the lung is the most common pulmonary malignancy, with incidence ranging from 30% to 55%. In autopsy series, the lung is the third most common site, after lymph nodes and liver.

1 Carcinomas are the major source of metastases to both lung and pleura, especially from the gastrointestinal tract, breast, and head and neck, followed by sarcoma and melanoma. In surgically resected tumors, slow-growing tumors are preferentially represented, including salivary gland tumors, renal cell carcinomas, and soft tissue sarcomas.

2 The most common tumor to metastasize to the pleura is lung carcinoma, through direct extension or through seeding resulting in a malignant effusion.

Metastatic disease of the lungs can occur by different mechanisms (

Table 94.1). Direct extension of tumor usually occurs from a contiguous neoplasm and mostly seen with primary thymic, esophageal, or thyroid neoplasms. Rarely, direct extension to the lung occurs via the vasculature, such as with renal cell carcinoma or germ cell tumor. True metastases can be defined as viable tumor cells transported from one site to another. They occur due to tumor spread via the vasculature, commonly the pulmonary arteries but also the lymphatic vessels and bronchial arteries. The embolized tumor cells often grow through the vasculature into the surrounding lung parenchyma, forming nodules. In some instances, the tumor cells remain confined to the vasculature and spread diffusely through the vascular channels, including lymphatic vessels. Metastases via bronchial arteries are thought to be much less common and perhaps result in endobronchial metastasis. Occasionally, tumor cells can be released into the pleural space and transported by the pleural fluid to a site of implantation. Tumor dissemination through the airspace is poorly understood and probably rare but thought to occur in some subtypes of lung cancer that metastasize to the lung without evidence of vascular or lymphatic spread.

Clinical and Radiologic Features

As metastases occur through different mechanisms, each route is usually associated with characteristic clinical, radiologic, and pathologic features, although overlap is frequent (

Table 94.1).

1

Parenchymal Nodules

The most common manifestation of metastatic disease to the lung consists of multiple nodules. The majority of patients with multiple metastatic tumor nodules have a previous or current history of malignancy. Patients are usually asymptomatic. Common symptoms include cough, hemoptysis, and wheezing. Chest pain occurs as a result of extension into pleura and chest wall. Although uncommon, cystic lung disease, occasionally presenting with spontaneous pneumothorax, may be the first manifestation of metastatic disease, usually from sarcomas.

CT scan is the most sensitive imaging modality to assess patients with multiple lung nodules, but because up to 60% of metastases are reported as 0.5 cm or less, the burden of metastatic disease can be underestimated. Also, CT scan is not entirely specific because granulomas or other benign processes also present as solid nodules. Metastatic tumor nodules are usually multiple, ranging in size from hardly visible to large masses capable of occupying an entire lung, with an average size of 1.0 to 2.0 cm. Mediastinal and hilar nodes are usually not enlarged. Pulmonary metastases are most commonly found peripherally, in the lower lobes. Rarely, the deposits are minute and numerous representing a miliary pattern. This miliary pattern has been described with medullary carcinoma of the thyroid, malignant melanoma, and prostatic carcinoma, among others. Cavitation has been reported in 4% of metastasis and occurs less commonly than with primary lung cancer. It has been described in metastatic squamous cell carcinoma, mainly from the head and neck or cervix; adenocarcinoma of the colon; and osteosarcoma. Calcification of metastatic lesions is rare and occurs in neoplasm with matrix production such as osteosarcoma or chondrosarcoma. It has also been described in neoplasms with psammoma bodies such as papillary carcinoma of the thyroid or through dystrophic calcification of mucin in mucinous adenocarcinomas from colon or other primary site. When calcified metastatic lesions are small, they can mimic benign lesions such as calcified granulomas.

Metastatic neoplasm presenting as a solitary nodule is uncommon, accounting for 1% to 5% of all lung metastasis and 2% to 10% of solitary pulmonary nodules. Neoplasms most likely to result in solitary metastasis are carcinoma of the colon, kidney, and breast; sarcomas, particularly osteosarcoma; and malignant melanoma.

Interstitial Thickening

Lymphangitic spread is an uncommon pattern of metastasis disease. It may mimic interstitial lung disease clinically and radiologically. This pattern can be seen with any primary tumors, but the most common include breast, stomach, pancreas, and prostate. Symptoms include dyspnea, typically with an insidious onset yet rapid progression over weeks.

The CT scan appearance is characterized by smooth to nodular thickening of the interlobular septa and peribronchovascular interstitium usually with preservation of the underlying lung parenchyma. The thickening is usually asymmetric. Associated pleural effusion is present in up to 30% of patients and hilar or mediastinal enlargement in up to 40%.

Pulmonary Hypertension and Infarct

Tumor involvement of pulmonary vessels is commonly seen at autopsy, often the cause of death. Most common primary sites resulting in tumor emboli include carcinoma of the stomach, pancreas, breast, and liver and choriocarcinoma. Patients are often asymptomatic. The most common symptom is dyspnea. Patients may develop subacute pulmonary hypertension with signs of cor pulmonale.

3 If the tumor emboli have resulted in infarcts, pleuritic chest pain, hemoptysis, or even sudden death can occur.

Radiologically, these lesions are difficult if impossible to diagnose. Indirect findings of pulmonary hypertension such as dilatation of the central pulmonary arteries and right ventricle can be identified, as well as infarcts. A ventilation-perfusion scan or CT scan with contrast may be helpful in identifying large tumor embolism.

Airway Obstruction

Neoplastic infiltration of the tracheal and main bronchial wall is a common finding at autopsy (19% to 51%), usually as the result of direct extension from parenchymal tumor or nodal metastasis. Metastasis presenting as a distinct, usually solitary, endobronchial mass is uncommon, between 2% and 4% of cases. The most common neoplasms resulting in an endobronchial mass are melanoma, sarcomas, and carcinomas from breast and kidney.

4 Symptoms consist of dyspnea, wheeze, persistent cough, and hemoptysis. Occasionally, expectoration of tumor fragment can occur.

Radiologic findings are those of partial or complete bronchial obstruction with air trapping, atelectasis, or obstructive pneumonia.

Pleural Effusion

The most common cause of exudative pleural effusion is malignancy, with gastric, breast, and ovarian carcinoma and lymphoma the most common primaries leading to pleural effusions.

2 Usually, the effusion occurs on the same side as the primary lesion and bilateral effusions are commonly associated with hepatic metastases. Several explanations for pleural effusions in the setting of cancer have been postulated

5: (1) Tumor involvement of mediastinal lymph nodes may contribute to pleural fluid accumulation. (2) Direct invasion of pleura results in inflammation, angiogenesis, and vascular leakage with the result of an exudative effusion.

6 Not all pleural effusions are considered malignant. In patients with lung cancer, an exudate effusion (proteinaceous with a low pH) may be presumptive evidence of metastasis even with negative cytology,

6 although documentation of malignant cells by cytologic or surgical pathologic examination is usually a requirement to confirm malignancy.

7 The reported incidence of positive cytologic examination in patients with malignant pleural effusion ranges between 35% and 85%. The highest diagnostic yield is with a thoracoscopic biopsy (91%), followed by ultrasound- or computed tomographic-guided biopsy (76%).

Diffuse Pulmonary Hemorrhage

Diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage (DPH) is an uncommon and unrecognized manifestation of neoplasm. Symptoms and signs of hemoptysis, anemia, and pulmonary alveolar infiltrates are similar to those seen in patients with nonneoplastic causes of DPH, although in patients with neoplasms, radiologic infiltrates will often be described as nodular, surrounded by ground-glass infiltrates.

Metastatic angiosarcoma is the most common neoplasm responsible for DPH. Other neoplasms reported to cause DPH include vascular neoplasms such as Kaposi sarcoma and epithelioid hemangioendothelioma and metastatic choriocarcinoma.

Pathologic Features

Gross

Parenchymal nodules are usually well circumscribed and of variable size. In cavitary nodules, the size of the cavity is often variable, ranging from < 1.0 cm to over 6.0 cm, and the walls are shaggy and thick, measuring between 0.3 and 2.5 cm. Blood, necrotic material, and rarely fungus ball can be identified within the cavity. In cystic metastasis, the wall is usually very thin, <0.3 cm and smooth and the cavity filled with air.

Lymphangitic carcinomatosis is characterized by thickening of the interlobular septa, peribronchovascular, and subpleural connective tissue. The thickening can be linear or nodular and is variable, from slight to obvious thickening of up to 1 cm.

Tumor emboli are usually not visible grossly unless larger, segmental arteries are involved. The appearance of tumor emboli is usually different from thromboemboli, with tumor emboli displaying a more solid, gritty or myxoid texture with white-beige color. Tumor emboli may be associated with an infarct.

Endobronchial metastasis can result in concentric narrowing of the airway or form a polypoid endobronchial mass.

Pleural metastases can vary widely from scattered small nodules to diffuse thickening with a solid rim of the pleura, mimicking mesothelioma.

The gross appearance of neoplasms presenting as DPH can vary with tumor type. In cases of metastatic angiosarcoma or Kaposi sarcoma, multiple subpleural and parenchymal hemorrhagic nodules are typically seen.

Microscopic Findings

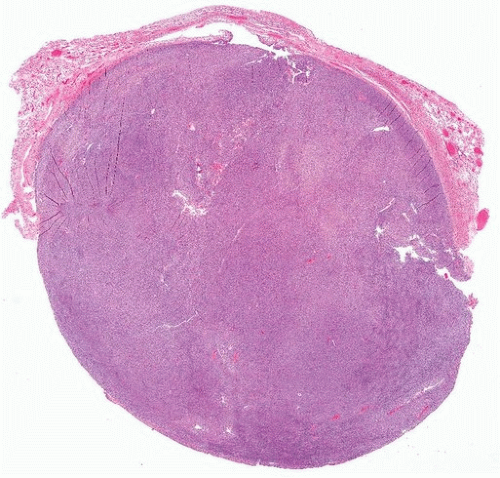

Macronodular metastases are typically sharply demarcated “cannonball lesions” (

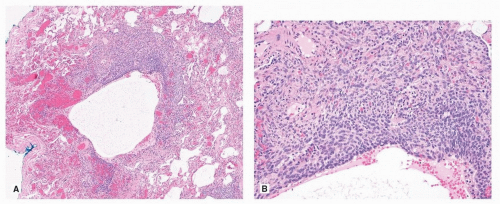

Fig. 94.1), a contrasting feature with primary lung carcinoma. Occasionally, metastases may be cystic rather than solid (

Fig. 94.2). Rarely, the growth pattern is lepidic, along intact lung architecture, mimicking a lepidic adenocarcinoma (

Fig. 94.3). This growth pattern is seen mainly in mucinous adenocarcinoma of the colon and pancreaticobiliary system.

1,2,8In lymphangitic carcinomatosis, the neoplastic cells are usually easily identified within the lymphatic spaces but also form cords and

clusters within the interstitium, usually associated with a desmoplastic reaction. Occasionally, the desmoplastic reaction is so prominent as to conceal the neoplastic cells, and the clue is the growth pattern along the lymphatic pathways (

Fig. 94.4).

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access