Most studies examining potential associations between psychological factors and cardiovascular outcomes have focused on depression or anxiety. The effect of perceived stress on incident coronary heart disease (CHD) has yet to be reviewed systematically. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between perceived stress and incident CHD. Ovid, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO were searched as data sources. Prospective observational cohort studies were selected that measured self-reported perceived stress and assessed incident CHD at ≥6 months. We extracted study characteristics and estimates of the risk of incident CHD associated with high perceived stress versus low perceived stress. We identified 23 potentially relevant articles, of which 6 met our criteria (n = 118,696). Included studies measured perceived stress with validated measurements and nonvalidated simple self-report surveys. Incident CHD was defined as new diagnosis of, hospitalization for, or mortality secondary to CHD. Meta-analysis yielded an aggregate risk ratio of 1.27 (95% confidence interval 1.12 to 1.45) for the magnitude of the relation between high perceived stress and incident CHD. In conclusion, this meta-analysis suggests that high perceived stress is associated with a moderately increased risk of incident CHD.

Measurements of stress in recent studies have been heterogenous and included disparate definitions such as caring for a demented partner or spouse, reporting of lack of general psychological well-being, or reporting the occurrence of negative life events such as divorce. Types of long-term stress that have consistently been associated with increased cardiovascular risk are work-related stress and marital stress. However, it may be that “perceived stress,” the general perception that environmental demands exceed perceived capacity regardless of the source of the environmental demand, is also consistently associated with incident coronary heart disease (CHD). To address this question, we conducted a systematic review of all prospective observational cohort studies that asked participants to report perceived stress and then followed those participants to assess incident CHD. Meta-analysis was used to derive an aggregate estimate of the risk ratio for the association between high perceived stress and incident CHD. We conducted sensitivity analyses to determine whether effect-size estimates differed by study characteristics.

Methods

We sought to identify all studies that reported a valid estimate of the association between perceived stress and incident CHD diagnosis, hospitalization for CHD, or mortality secondary to CHD. To be included, studies must have been prospective observational cohorts that featured a self-report assessment of perceived stress on which participants could report the frequency and/or intensity of stress. Only studies that used measurements specifically referencing “stress” and not symptoms of psychological disorders such as depression, anxiety, or post-traumatic stress disorder were included in this review.

We searched the electronic databases Ovid, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO for potentially relevant articles. Dates included in the search were 1948 to July 21, 2011, the date the search was conducted. All relevant subject heading and free text terms were used to represent stress and CHD and the sets of terms were combined with “and.” Terms for MEDLINE to represent stress included: exp Stress, Psychological/OR (Psycho$ or mental$ or emotion$ or financ$ or marital or relationship$ or social$ or job$ or occupation$ or employ$ or work$ or global) adj5 (stress$ or distress$)).tw. OR exp Stress Disorders, Traumatic/OR http://ptsd.tw . OR (post-traumatic OR (post adj traumatic)).tw OR http://posttraumatic.tw . Terms to represent CHD included: exp Myocardial Ischemia/OR (coronary or heart or isch? emi$ or myocardial or cardiac) adj3 (disease$ or syndrome$ or attack$ or event$)).tw. OR (acs or acd or chd or cad).tw. OR ((post adj acs) or postasc).tw. These terms were adapted for PsycINFO. Additional records were identified by scanning the references lists of relevant studies and reviews and by employing the Related Articles feature in PubMed and the Cited Reference Search in ISI Web of Science.

To determine the studies to be assessed further, 2 authors (S.R. and L.F.) independently read the abstract and/or titles of every record retrieved for the selection criteria listed below. All potentially relevant articles were investigated as full text. Differences in opinion were resolved by consensus.

We abstracted effect-size estimates and study characteristics of those studies describing the association of perceived stress to incident CHD diagnosis, hospitalization for CHD, and mortality secondary to CHD ( Table 1 ). For multiple publications from the same cohort, we chose the publication with the largest sample and the most appropriate outcome measurement (e.g., Nielsen et al was included because it measured incident CHD diagnosis, whereas Nielsen et al measured death secondary to CHD without excluding participants with a previous diagnosis of heart disease). All studies were coded for the following characteristics: sample size; years of follow-up; specific measurement of perceived stress and scoring procedure; cardiovascular outcomes measured; sample age, gender, and race/ethnicity; year of publication; number of covariates; and adjustment for psychological variables.

| Source | Risk Approximation | Perceived Stress Measurement | Time to Follow-Up (months) | CHD Outcome | Subjects | Men | Mean Age (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iso et al, 2002 | 1.51 (0.97–2.37) | question | 94.8 | death | 73,424 | 41% | 60 |

| MacLeod et al, 2002 | 1.00 (0.76–1.32) | Reeder Stress Inventory | 252 | admission | 5,606 | 100% | 48 |

| Nielsen et al, 2006 | 1.24 (1.07–1.44) | question | 216 | diagnosis | 11,839 | 48% | 56 |

| Ohlin et al, 2004 | 1.15 (0.99–1.34) | question | 255 | diagnosis | 13,609 | 80% | 44 |

| Rosengren et al, 1991 | 1.50 (1.19–1.89) | question | 142 | diagnosis | 6,935 | 100% | 51 |

| Strodl et al, 2003 | 1.67 (1.17–2.38) | Perceived Stress Scale | 36 | diagnosis | 6,994 | 0% | 73 |

Comprehensive Meta-Analysis 2 (BioStat Software, Englewood, New Jersey) served as the statistical platform for completing all statistical tests and producing associated graphic results. We calculated an aggregate effect size in the form of a risk ratio associated with high versus low perceived stress on incident CHD diagnosis, hospitalization for CHD, or mortality secondary to CHD.

Log-transformed risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for each study using the reported effect size and estimates of the SE of the effect size from data reported in the article. To assess heterogeneity in effect-size estimates across studies, we calculated the Cochran Q, which is the weighted sum of squared differences between individual study effects and the pooled effect across studies, although it has low power for detecting heterogeneity when the number of studies in a meta-analysis is small. We also report I 2 , which is the percent between-study variance in effect sizes that is caused by heterogeneity rather than chance. When articles reported multiple models, we selected the effect size from the most fully adjusted model. To address possible publication bias, we examined the funnel plot associated with the study effect sizes and calculated a fail-safe number.

In addition to overall fixed- and random-effects meta-analysis models, we used sensitivity analyses to assess possible moderator effects for the association of perceived stress to CHD outcomes across some methodologic factors. These factors included the measurement used to assess perceived stress and the type of CHD or mortality outcome. Further, meta-regression analysis was used to test the association between effect size and study publication date and mean sample age. Separate estimates for men and women were available in 3 studies, so we were able to compare the association by gender. Similarly, separate estimates were available for cardiac events with and without angina in 3 studies, so we also compared those effect-size estimates.

Results

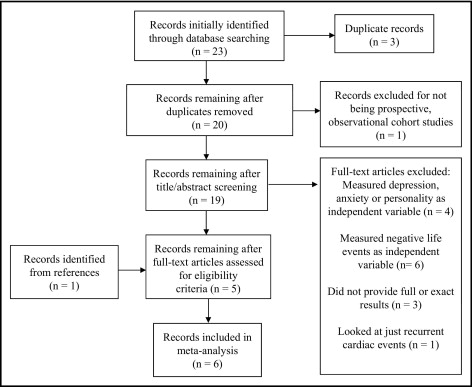

Among 23 articles identified in our initial search, 19 required full reading after duplicate records were excluded. Of these 19, 6 met our criteria for inclusion (5 articles from the initial search and another article identified from the references ; Figure 1 ).

All included studies completed recruitment and assessment of baseline characteristics from 1970 through 1990. Follow-up periods ranged from 36 to 255 months with an average of 165.9 months of follow-up (or 13.8 years). Studies were conducted in Sweden, (2) Scotland (1), Australia (1), Denmark (1), and Japan (1). Two studies enrolled men only and 1 enrolled women only. For the remaining 3 studies, the average percent sample that was men was 56.4%. Mean age for all study participants was 55.0 ± 10.18 years. Two studies used validated measurements of perceived stress, and 4 asked 1 question or 2 questions about the experience of daily stress ( Table 2 ).

| Study | Validated Measurement | Measurement | Scale | High Stress Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iso et al, 2002 | 0 | What is the level of stress in your daily life? | low, medium, high, extremely high | high or extremely high |

| MacLeod et al, 2002 | + | Reeder Stress Inventory | 1–8 | score 6–8 |

| Nielsen et al, 2006 | 0 | Do you feel stressed? | none, light, moderate, high (0–3) | combined score 5–6 |

| How often do you feel stressed? | never, monthly, weekly, daily (0–3) | |||

| Ohlin et al, 2004 | 0 | Have you experienced permanent stress during the previous year? | yes/no | yes for either question |

| Have you experienced permanent stress during the previous 5 years? | yes/no | |||

| Rosengren et al, 1991 | 0 | Ever experience stress? | never, ≥1 period, some period during previous 5 years, several periods during previous 5 years, permanent stress during previous year, permanent stress during previous 5 years (1–6) | score 5–6 |

| Strodl et al, 2003 | + | Perceived Stress Scale | 0–4 | score 2–4 |

One of the included studies used the Perceived Stress Scale, which was designed to measure the degree to which subjects appraise situations in their lives as stressful. The Perceived Stress Scale uses paper-and-pencil self-report, takes about 5 minutes to complete, and evaluates the degree to which subjects find life unpredictable, uncontrollable, or overloaded. Validity and reliability were assessed in a large national probability sample (n = 2,387) in the United States. Another study used the Reeder Stress Inventory, which consists of 4 statements about feelings of strain, tension, exhaustion, and stress in association with daily activities. Respondents rate the extent to which each of these 4 statements is true using a 4-point Likert format. This measurement was validated in a cross-sectional investigation (n = 1,717) in the United Kingdom.

The remaining studies asked 1 question or 2 questions about the intensity and/or frequency of daily stress. The nature of these questions was similar to questions included in the validated measurements of perceived stress. Thresholds for labeling participants as experiencing high stress were similar across all studies where participants had to directly report intense or frequent feelings of stress ( Table 2 ).

Cardiac outcomes included death from CHD, incident CHD diagnoses and events (including angina), and hospital admission for CHD. Every study controlled for traditional cardiac risk factors (e.g., age, blood pressure, smoking, cholesterol), 3 studies also controlled for socioeconomic status, and another study controlled for depression and anxiety symptoms.

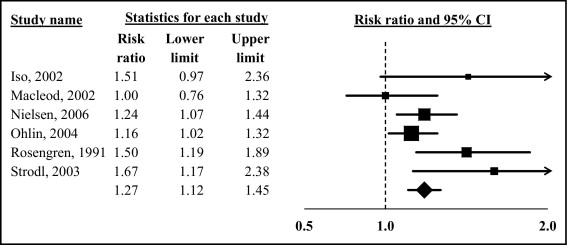

The aggregated effect size associated with high versus low perceived stress for incident CHD was a risk ratio of 1.27 (95% CI 1.12 to 1.45) in the random-effects model ( Figure 2 ). There was no statistically significant between-study heterogeneity in effect-size estimates (Q[5] = 9.54, p = 0.09). However, because the p value for the significance test of the assessment of heterogeneity was <0.10, we decided to report the random-effects estimate and conduct our a priori sensitivity analyses by study characteristics, with the understanding that the lack of heterogeneity and small number of studies limited our power to detect associations between study characteristics and effect-size estimates.