Fig. 8.1

Ultrastructure of the measles virus showing a spherical, enveloped virion with a non-segmented negative-stranded RNA genome (With permission from Lancet [Reproduced with permission of Exp. Rev. Mol. Med 30, 1–18. © Cambridge University Press])

The major component of the nucleoprotein core is the ribonucleoprotein. The other two parts are the large protein and the phosphoprotein. The large protein is composed of the enzyme RNA polymerase, which catalyzes the transcription and replication of the nucleocapsid template (Yanagi et al. 2006).

The envelope is made up of a matrix protein, a hemagglutinin protein, and a fusion protein. The attachment of the virions to the host cell is mediated by the hemagglutinin protein; following this process, the fusion and hemagglutinin proteins mediate entry into the host cell. The known measles virus receptors on human cells are the signaling lymphocyte activation molecule (SLAM) CD1506 and the membrane cofactor protein CD46, a regulator of complement activation that plays an important part in protecting host cells from spontaneous complement attack (Yanagi et al. 2006). Measles virus has only one serotype and can, therefore, be prevented with a single monovalent vaccine.

8.5 Pathogenesis

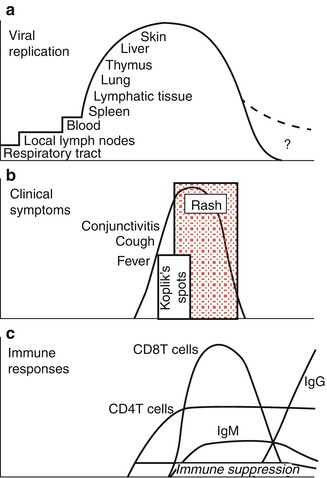

Infected persons transmit MV via respiratory droplets delivering infectious virus to epithelial cells of the respiratory tract of susceptible hosts. During the incubation period MV replicates and spreads in the infected host. Type 1 pneumocytes, alveolar macrophages, and respiratory epithelial cells become infected but is yet unknown which is the initial site of viral replication. The virus then spreads to local lymphatic tissue, and this replication is followed by viremia and dissemination to many organs, including the lymph nodes, skin, kidney, gastrointestinal tract, and liver, in which the virus replicates in the epithelial and endothelial cells and in lymphocytes, monocytes, and macrophages (Griffin 2010). Measles immunity involves humoral, cellular, and mucosal responses. Cell-mediated immunity is required for recovery from measles, and humoral immunity is associated with protection from infection or reinfection (Moss and Griffin 2012).

MV infection results in immunosuppression with depressed responses to non-MV antigens. This effect lasts for several weeks to months after resolution of the acute illness. Patients with measles showed suppressed delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) responses to recall antigens, such as tuberculin, and impaired cellular and humoral responses to new antigens. This MV-induced immune suppression renders individuals more susceptible to secondary bacterial and viral infections that can cause pneumonia and diarrhea and is responsible for much of the measles-related morbidity and mortality (Moss and Griffin 2006). Pneumonia, the most common fatal complication of measles, occurs in 56–86 % of measles-related deaths (Duke and Mgone 2003). The production of IL-12 is reduced while the production of IL-10, which inhibits DTH responses and downregulates the synthesis of cytokines and suppresses macrophage activation and T-cell proliferation, is elevated for several weeks in the plasma of children with measles (Yanagi et al. 2006). The measles skin rash is thought to be caused by the T-cell response to MV-infected cells in capillary vessels because it does not appear in children with T-cell immunodeficiency (Yanagi et al. 2006).

8.6 Clinical Features

After an incubation period of 10–14 days, prodromal measles begins with fever of 39–40 C, cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis (Fig. 8.2). The initial presentation resembles a cold except that fever is an early sign. These symptoms worsen over a 2- to 4-day period; sneezing, rhinitis, and congestion are common. The cough is frequently troublesome and often has a brassy quality, suggesting laryngeal and tracheal involvement. If the mucous membranes lining the cheeks opposite the molar teeth are examined, there will be found in the majority of patients a few white to bluish-gray spots the size of a pinhead with red margins. These are known as Koplik’s spots and are a pathognomonic exanthem of measles.

Fig. 8.2

Schematic reproduction of the pathogenesis of measles from virus infection to recovery (With permission from Lancet [Reproduced with permission of Griffin, D.E. Measles virus-induced suppression of immune responses. (a) viral replication. (b) clinical symptoms. (c) immune responses. Immunological Reviews June 15, 2010, pp 176–189. © John Wiley & Sons])

The rash starts behind the ears and spreads to the face and trunk within 24 h. The rash is deep pink or red in color, appeared in blotches scattered as little islands with unaffected skin between, and is pruritic. The rash then spreads to cover the entire body in about 3 days (Kilbourne 1967). It is unusual for the rash to persist more than 5–7 days, and when it fades the skin appears dry while the superficial layers scale off. The fever usually lasts 5–7 days. Within 5 days of the appearance of the rash, most children are up and about (Towsley 1947).

Complications of measles are largely attributable to the pathogenic effects of the virus on the respiratory tract and immune system (Axton 1979). Acute otitis media is the most common complication, and pneumonia is the most common cause of death in measles. Croup, tracheitis, and bronchiolitis are common complications in infants and toddlers with measles (Moss and Griffin 2012; Duke and Mgone 2003; Perry and Halsey 2004). Pneumonia is a severe complication of measles and as noted accounts for most measles-associated deaths. In studies of unselected hospitalized children with measles, 55 % had radiographic changes of bronchopneumonia, consolidation, or other infiltrates; 77 % of children with severe disease and 41 % of children with mild disease had radiographic changes. In recent years, pneumonia was present in 9 % of children <5 years old with measles in the United States, in 0–8 % of cases during outbreaks, and in 49–57 % of adults.

Pneumonia may be caused by the measles virus alone, secondary viral infection with adenovirus or HSV, or secondary bacterial infection. Measles is one cause of Hecht’s giant cell pneumonia, which usually occurs in immunocompromised persons but can occur in otherwise normal adults and children. Studies that included culture of blood, lung punctures, or tracheal aspirations revealed bacteria as the cause of 25–35 % of measles-associated pneumonia. S. pneumoniae, S. aureus, and H. influenzae were the most commonly isolated organisms. Other bacteria (e.g., Pseudomonas species, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and E. coli) are less common causes of severe pneumonia associated with measles. In studies of young adult military recruits with pneumonia associated with measles, Neisseria meningitidis was a probable cause in some cases (Perry and Halsey 2004; Enders et al. 1959; Mitus et al. 1959; Ellison 1931). Diarrhea and vomiting are common symptoms associated with acute measles; appendicitis may occur from obstruction of the appendiceal lumen by lymphoid hyperplasia. Febrile seizures occur in <3 % of children with measles (Moss and Griffin 2012; Duke and Mgone 2003).

Measles infection is known to suppress skin test responsiveness to purified tuberculin antigen. There may be a higher rate of activation of pulmonary tuberculosis in populations of individuals infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis who are then exposed to measles (Griffin 2010). The three most serious complications of measles occur in the CNS. These are acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis (ADEM), measles inclusion body encephalitis (MIBE), and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE); the last two are invariably fatal. ADEM develops a week after the appearance of the rash and is seen in 1:100 infected children. Approximately 15 % of patients with ADEM die, and 20–40 % suffer long-term sequelae, including mental retardation, motor disabilities, and deafness. MIBE is seen in immunocompromised patients between 2 and 6 months after acute infection or vaccination. SSPE is caused by a persistent measles virus infection and develops years after the initial infection (Rima and Duprex 2006; Perry and Halsey 2004). Findings in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) include lymphocytic pleocytosis in 85 % of cases and elevated protein concentration.

A severe form of measles rarely seen now is hemorrhagic measles or “black measles.” It manifested as a hemorrhagic skin eruption and is often fatal. Keratitis, appearing as multiple punctate epithelial foci, resolved with recovery from the infection. Thrombocytopenia sometimes occurred following measles (Kilbourne 1967). Myocarditis is a rare complication of measles. Miscellaneous bacterial infections have been reported, including bacteremia, cellulitis, and toxic shock syndrome. Measles during pregnancy has been associated with high maternal morbidity, fetal wastage, stillbirths, and congenital malformations in 3 % of live born infants (Moss and Griffin 2012).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree