Management of the Diabetic Foot

Scott A. Berceli

Peripheral neuropathy, often in combination with local tissue ischemia, leads to repetitive unrecognized trauma and development of ulceration in the diabetic foot. Approximately 15% of patients with diabetes will develop foot ulceration in their lifetime, leading to 82,000 major limb amputations per year, at a cost of $1.1 billion. More than 60% of nontraumatic leg amputations performed in the United States occur in the diabetic population.

Pathogenesis

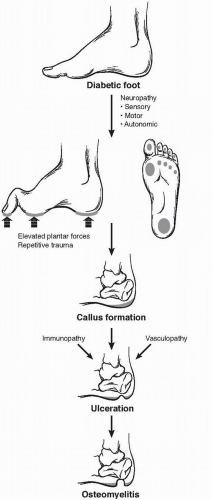

A constellation of physiologic and metabolic disturbances coalesces in the diabetic patient, leading to breakdown of the skin and ulcer development (Fig. 61-1). Exacerbated by a combination of peripheral neuropathy, vascular insufficiency, and impaired immunologic function, ulcer healing is suboptimal and prone to extension into surrounding soft tissue and bone. Repeated trauma promotes conversion from an acute to chronic wound, characterized by an accumulation of extracellular matrix, excessive matrix metalloproteinase activity, and an inability to advance from the inflammatory phase of wound healing.

The factor most consistently associated with foot ulceration in diabetes is the presence of peripheral neuropathy. Loss of sensation leads to a patient being unaware of a foreign body in the shoe, a blister from improperly sized footwear, or scalding bath water. Motor fibers are also affected in a “stocking and glove” distribution. The resulting atrophy of the lumbrical and interosseous muscles of the foot leads to collapse of the arch and loss of stability of the metatarsal-phalangeal joints. Weakness of these intrinsic muscles, and the relative dominance of the extrinsic musculature, produces depression of the metatarsal heads, hammertoe contractures of the digits, and equinus deformities of the ankle. These changes result in an altered gait with focal regions of elevated plantar pressure and increased surface shearing force. The coalescence of this increased laxity and loss of sensation leads to the “rocker-bottom” Charcot foot, characterized by bony fractures and joint subluxation. Contributing to skin breakdown is the loss of autonomic innervation of the foot, with impaired microvascular thermoregulation and anhidrosis. The resulting dry, cracked skin provides a potential entry point for bacterial invasion and initiation of infection.

While not universally present, ischemia contributes to approximately one-third of diabetic foot ulcers. Peripheral arterial occlusive disease in these patients typically involves the tibial arteries, with relative sparing of the pedal and peroneal vasculature, making these suitable distal targets for revascularization. While autonomic dysfunction of the microvasculature is also seen in these patients, extensive “smallvessel” occlusive disease is not characteristic of the disease process and does not preclude restoration of pulsatile flow to the foot, a cornerstone to limb salvage therapy.

The underlying etiology of the immunologic dysfunction is not well understood but stands as the third component in the development of diabetic foot ulcers. Among the defects in host immune defenses seen in diabetic patients are altered leukocyte activity and complement function. Immune responses are further impaired by poor glycemic control, supporting the clinical observation of hyperglycemia as an independent risk factor. The impact is a twofold increase in the risk of limb loss in patients with poorly controlled blood glucose levels.

Preventive Care

Approximately three-quarters of diabetic patients requiring major amputation follow the classic scenario of minor trauma leading to cutaneous ulceration, complicated by wound-healing failure, and ending in leg amputation. In one series, shoe-related trauma was the causative insult in 36% of all cases, accidental cuts or puncture wounds in 8%, thermal injury (frostbite or burns) in 8%, and decubitus ulceration in 8%.

Critical to improving care and reducing these events is regular evaluation by a skilled practitioner and patient education with instruction in self-examination techniques. Current clinical guidelines recommend a comprehensive foot exam at least once yearly for all diabetics, with more frequent exams in individuals identified at high risk for ulceration. Patients in the high-risk group are identified as having one of the following:

Musculoskeletal deformities of the foot

Loss of peripheral sensation

Peripheral vascular occlusive disease

History of previous foot ulceration

Clinical evaluation should include:

Inspection of the foot and toes for deformities, calluses, blisters, or open ulcers

Assessment of pedal pulses

Sensory testing of the plantar foot

Among the most important tools to objectively evaluate sensation is the 5.07 (10g) Semmes-Weinstein nylon monofilament, designed to deliver 10-gram force when applied perpendicular to the skin surface in a slow, continuous manner until the monofilament bends. While extensive examination protocols using this device have been devised, good sensitivity and specificity to detect the insensate foot can be achieved

through testing the plantar aspect of the first and fifth metatarsal heads.

through testing the plantar aspect of the first and fifth metatarsal heads.

Patient education is potentially the most critical element in maintaining a healthy diabetic foot, with daily self examination the cornerstone in prevention. In patients with limited mobility or visual impairment, involvement of family members in this task is critical. Application of lotion can moisturize dry skin, preventing breakdown of this important barrier to infection. Identified corns or calluses should be treated by a professional care provider, avoiding “home surgery” with chemical agents or sharp debridement. Shoes and stockings worn both indoors and outdoors can minimize foot trauma, and patients should be instructed to seek medical attention if a blister, cut, or sore is identified. Inappropriate footwear is a major cause of ulceration, and instruction in this area is vital. Shoes should not be too tight or loose and are best purchased later in the day, while wearing appropriate stockings. Appropriately sized shoes are 1 to 2 cm longer than the foot itself, with a shoe height adequate to accommodate hammertoe contractures if present. Patients with signs of abnormal loading of the foot (evidenced by hyperemia, calluses, or ulceration) are best treated with custom footwear.

Clinical Assessment

Properly assessing both the patient and the foot wound is the first step in developing a rational approach for treatment. Lesions can rapidly deteriorate, with involvement of surrounding bone, and they can spread along fascial planes and tendon sheaths. Consequently, early diagnosis and accurate evaluation are critical for achieving limb salvage. Key points of the medical history include identifying the initial traumatic event, the duration of the ulcer, the methods of treatment, and the clinical progression of the wound. Systemic signs of toxicity (fevers, malaise, leukocytosis, or poor serum glucose control) should be investigated and usually represent a late but ominous sign of a deep space infection. Pain is frequently absent in these neuropathic patients and is often a poor indicator of the extent of infection. Recent symptoms of vascular insufficiency (claudication or rest pain) should also be elicited.

Physical exam involves inspection of the entire foot and leg, examining for signs of ascending infection and overall quality of the skin. Carefully describe ulcers, including size, depth, location, drainage, necrosis, and surrounding erythema. Palpate the foot for evidence of crepitus and tenderness tracking along tendon sheaths. Breaks in the skin should be explored using a probe to identify sinus tracts, extension along fascial planes, and involvement of joint spaces. Probing to bone stands as an excellent test for osteomyelitis, with a positive predictive value approaching 90%.

Detailed lower-extremity pulse exam, in combination with physiologic arterial testing, should be performed to evaluate the

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree