LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Learning Objectives

The student will be able to describe the symptoms and signs of patients presenting with restrictive lung diseases.

The student will be able to define the pathophysiological mechanisms of specific restrictive lung diseases.

The student will be able to use clinical, physiological, and chest imaging data to differentiate patients with various forms of restrictive lung diseases.

The student will be able to provide a stepwise approach to the diagnosis and treatment of patients with selective restrictive lung diseases.

Restrictive lung diseases comprise a heterogeneous group of >100 different respiratory disorders whose common denominator is a pathological reduction in lung volume. The reduced volume may result from diffuse inflammatory injury, as well as abnormal fibrotic proliferation and repair within alveolar walls and the lung’s interstitial structures. Such disorders are collectively designated interstitial lung diseases (ILDs). Many ILDs not only lead to thickening of alveolar walls and septal interstitium, but also of the lumina and walls of small airways (alveolar ducts, respiratory bronchioles, and terminal bronchioles) and the pulmonary capillary network. Chest wall disorders and certain neuromuscular diseases that adversely influence the mechanical efficiency of the muscles of respiration also culminate in pulmonary restriction, albeit without ILD-like pathophysiological features in the lung parenchyma. Regardless of the specific etiology of an ILD and its pathophysiological mechanisms, the presenting clinical manifestations usually include three hallmark features: (1) progressive dyspnea on exertion; (2) restrictive physiology on pulmonary function tests; and (3) diffuse reticular infiltrates or ground-glass opacities on chest radiographs or thoracic CT imaging studies.

INTERSTITIAL LUNG DISEASES

To facilitate a differential diagnosis of ILD, it is helpful to view the condition as associated with ten broad disease categories affecting the respiratory system (Table 24.1). These general categories will be considered in turn.

| Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias | Sarcoidosis |

| Connective tissue diseases | Eosinophilic lung disorders |

| Hypersensitivity pneumonitis | Pulmonary vasculitides |

| Pneumoconioses | Alveolar hemorrhage syndromes |

| Drug-induced pulmonary disease | Miscellaneous disorders |

IDIOPATHIC INTERSTITIAL PNEUMONIAS

Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias are a group of lung disorders comprised of: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF); nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP); cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP); acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP) or Hamman-Rich syndrome; respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease (RB-ILD); desquamative interstitial pneumonitis (DIP); and lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP). Each of these disorders has characteristic histopathological features which permit their presumptive distinction (Table 24.2; see Chap. 23).

| Histological pattern | Clinical/Radiologic/Pathologic Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Usual interstitial pneumonia | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis |

| Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia | Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia |

| Organizing pneumonia | Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia |

| Diffuse alveolar damage | Acute interstitial pneumonia |

| Respiratory bronchiolitis | Respiratory bronchiolitis interstitial lung disease |

| Desquamative interstitial pneumonia | Desquamative interstitial pneumonia |

| Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia | Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia |

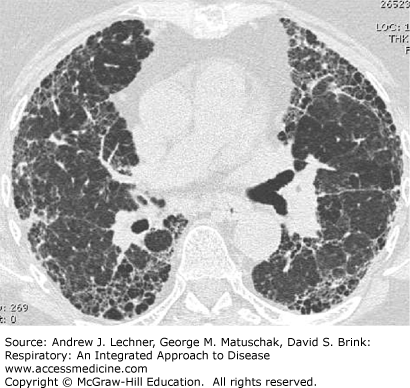

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is the most important and common idiopathic interstitial pneumonia and, in many ways is a prototypic ILD and restrictive lung disease with respect to symptoms, physical findings, and laboratory features. IPF affects at least 200,000 persons in the United States, whose median survival is 3-5 years from diagnosis. The exact cause of IPF is not known. Interestingly, 0.5%-3.7% of cases of IPF are familial, and 60% of patients diagnosed with this disorder have a positive history of smoking. The incidence of IPF increases significantly in older adults, being most common between the ages of 50 and 70 years. High-resolution chest CT (HRCT) findings in IPF may be pathognomonic when demonstrating patchy, heterogeneous and subpleural, peripheral reticular opacities and septal thickening usually found in conjunction with honeycombing and traction bronchiectasis (Fig. 24.1). Histopathologically, IPF is a common although not exclusive idiopathic etiology for usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP). Presenting symptoms in IPF include dyspnea on exertion in 90% of patients and nonproductive cough in >70% of subjects. Bibasilar inspiratory Velcro-like crackles predominate in 85% of IPF patients on physical examination whereas digital clubbing occurs in at least 25% (Chap. 14). Pulmonary function test abnormalities include restrictive ventilatory limitations characterized by a normal or increased FEV1/FVC ratio together with a TLC that is <80% of predicted or the lower limit of normal (LLN). Characteristically, the single breath DLCO is reduced, and patients manifest mild to moderate arterial hypoxemia or decreasing SaO2 during exertion (Chaps. 16 and 17).

Predictors of reduced survival in IPF include coexisting emphysema and the presence of pulmonary hypertension as reflected by elevated PPA estimated using transthoracic echocardiography or documented during right heart catheterization. Physiological predictors are reduced FVC, TLC, and DLCO at the time of diagnosis and then further declines in FVC and DLCO over the succeeding 6-12 months. Additionally, a significantly reduced distance during the six-minute walk test (6-MWT) and exertional decline in Sao2 correlate with increased mortality. Causes of death in IPF include coronary artery disease, lung cancer, infection, and pulmonary embolism.

IPF is generally a chronic and relentlessly progressive disorder. However, acute and frequently fatal exacerbations can occur at any time and are increasingly recognized as a major cause of death during which rapid progression of disease occurs within 4 weeks. Such acute exacerbations of IPF are not related to the severity of underlying PFT abnormalities, and are often heralded by low-grade fever, flu-like symptoms, and worsening cough with dyspnea. Such findings occur in association with severe arterial hypoxemia and newly developing diffuse radiographic opacities that are superimposed on the baseline reticular pattern, often in the absence of infectious pneumonia, heart failure, pulmonary thromboembolism, or sepsis. Histopathologically, diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) is generally found in patients with a background of UIP. The rate of acute exacerbations ranges from 10% to 15% per year and the risk factors are unknown. These exacerbations carry a hospital mortality rate of 78%, and recurrence among survivors of another acute exacerbation is common and usually results in death.

SARCOIDOSIS

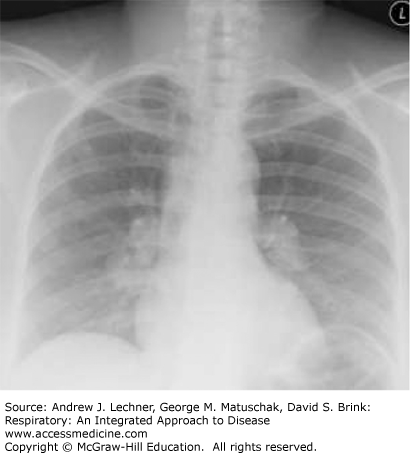

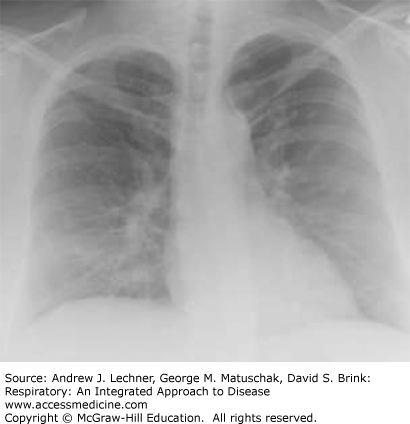

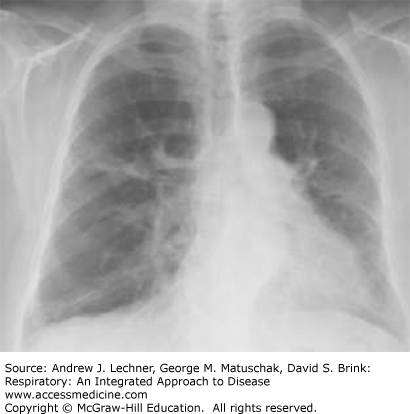

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disorder that is characterized by the formation of non-necrotizing, well-formed granulomas in multiple organ systems. With respect to the lungs, T-helper cell (CD4+) lymphocyte-mediated inflammation plays a key pathogenetic role. Sarcoidosis is a relatively common cause of ILD in young and middle-aged adults, but not all patients with sarcoidosis have pulmonary symptoms. Regardless, there is usually incidental radiographical evidence of lung and intrathoracic lymph node involvement, which is classically distinguished by four stages using standard chest x-rays (Table 24.3; Figs. 24.2, 24.3, 24.4, 24.5).

| Stage | Intrathoracic Manifestations |

|---|---|

| I | Bilateral hilar adenopathy |

| II | Bilateral lymphadenopathy and reticulonodular infiltrates/opacities |

| III | Bilateral reticulonodular infiltrates/opacities |

| IV | Fibrocystic changes with bullae, upper lobe fibrotic scarring, and upward hilar retraction |

CLINICAL CORRELATION 24.1

The clinical, laboratory, radiographic, and histopathological characteristics of sarcoidosis are closely simulated by berylliosis (chronic beryllium disease), a chronic hypersensitivity response of the lungs to beryllium fumes or dust that results in granulomatous inflammation (Chap. 23). Lung specimens in berylliosis showing non-necrotizing (noncaseating) granulomas are indistinguishable from lungs of patients with sarcoidosis and occasionally, tuberculosis. The diagnosis requires lung biopsy and evidence of sensitivity to beryllium by lymphocyte proliferation testing of the patient’s blood or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Occupations associated with beryllium exposures include scrap metal working, automotive or aircraft electronics, and some oil and gas industries.