A primary aortoenteric fistula can be a devastating and life-threatening condition that can be as difficult to diagnose as it is to treat. In a review of 118 cases by Sweeney and Gadacz, 97 patients (82%) died either before the diagnosis was made or during attempted treatment. Initial symptoms in this review were hematemesis (40%), melena (40%), abdominal pain (48%), and back pain (22%). In essentially all reported series, bleeding is by far the most common symptom, occurring in up to 94%, whereas abdominal or back pain occurs less commonly, in less than 50%. Reviews indicate that from 33% to 61% of patients arrive at the hospital in shock. The classic diagnostic triad of abdominal, back, or flank pain; gastrointestinal hemorrhage; and a palpable abdominal mass occurs even less commonly, being 11% in Saers and Scheltinga’s review. When the thoracic aorta is involved, the pain tends to be substernal, and it can obviously be mistaken for myocardial ischemia.

Hemorrhage is the overwhelming cause of death for most patients, but the initial presentation can be misleading: Patients typically have a history of intermittent gastrointestinal bleeding. The initial episode is often referred to as the herald or sentinel bleed. It may be minor and self-limited, best explained by a transient drop in blood pressure associated with the initial bleeding combined with contraction of the bowel in response to the stream of blood, resulting in a lessening of bleeding from the fistula. As the aortic pressure subsequently increases and the clot lyses or becomes dislodged, the hemorrhage recurs and often does so in massive and dramatic fashion, causing death before treatment can be completed.

The interval between bleeding episodes can be advantageous if it provides sufficient time to institute appropriate treatment. However, this requires that the diagnosis be quickly considered and made. In a review of 115 patients by Reckless, McColl, and Taylor, the length of time from first gastrointestinal bleed to massive exsanguination and death or surgical intervention was less than 6 hours in 30%, 6 to 24 hours in 17%, 1 to 7 days in 31%, and longer than 7 days in 37% of patients. In another report, the median interval was 4 days. Nevertheless, prolonged delays in treatment invariably increase the risk for massive bleeding and death.

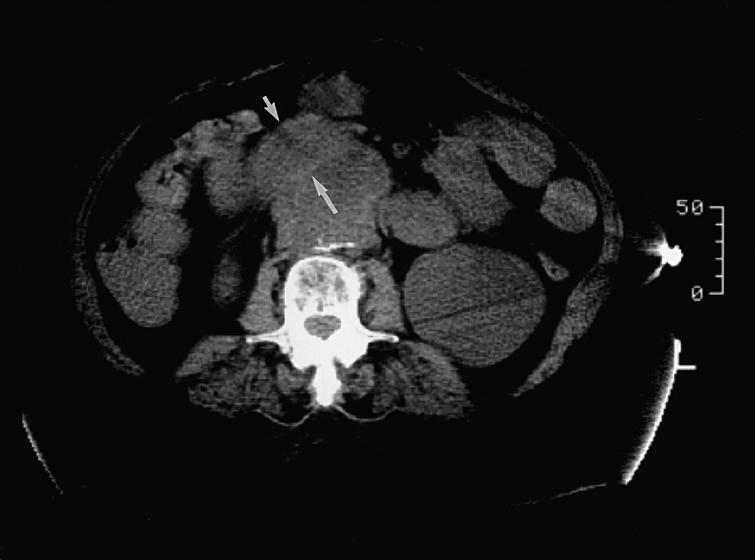

A correct preoperative diagnosis has been notoriously difficult to make despite this time interval, and the majority of cases are not correctly diagnosed until surgical exploration or postmortem examination. There is little utility in plain radiographic studies, which document the presence of AAAs in about only 55% of patients. The most useful and easiest study is contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT). Although the findings can sometimes be subtle and not definitive, the most specific finding is the presence of extraluminal gas in the periaortic region or gas within the calcified rim of an aneurysm that is in close association with an adherent loop of bowel. Another positive finding is fluid-filled loops of bowel, which suggests recent hemorrhage, draped over an AAA, with loss of the periaortic fatty plane (Figure 1). Because of the possibility of esophageal involvement, the CT scan should include the chest. There is little published information on the usefulness of other imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron-emission tomography CT (PET-CT), and radionuclide scans, but these could be helpful in individual cases.

Only gold members can continue reading.

Log In or

Register to continue

Related

![]()