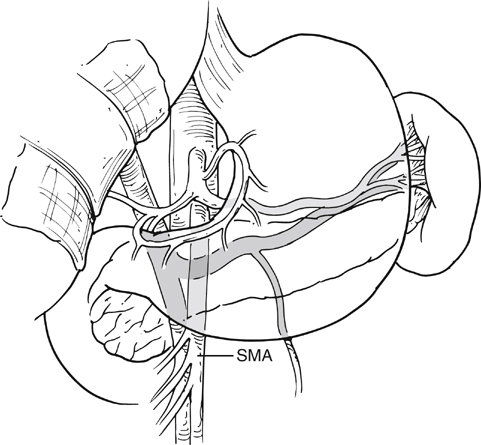

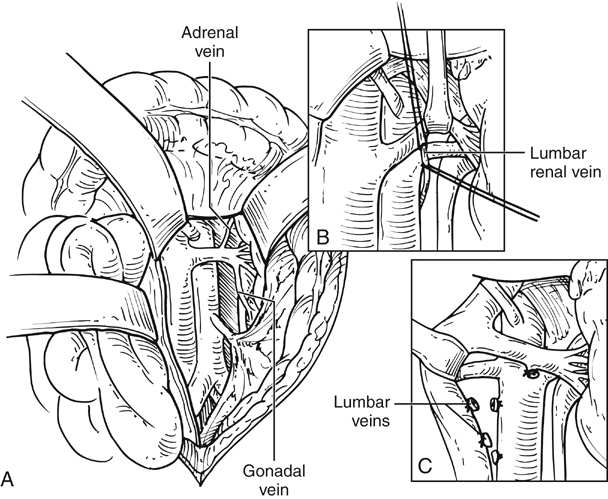

The median arcuate ligament and the crus of the diaphragm are incised to expose the underlying aorta; this can be facilitated by incising the muscle fibers between the jaws of a large right-angle clamp using electrocautery (Figure 1). The dissection of the aorta cephalad to the celiac artery can be exposed relatively quickly, although care should be exercised in the segment adjacent to the celiac artery to avoid inadvertent injury to the vessel. Additionally, a dense neural plexus, further complicating the dissection, encases the origin of the celiac artery. The pararenal aorta and the renal arteries themselves may then be exposed by retracting the left renal vein cephalad and caudad as necessary. The suprarenal aorta can then be exposed to the base of the SMA by retracting the pancreas cephalad and incising the investing dense neural plexus. The origin of the SMA and its proximal few centimeters can be exposed with this approach, and it is our preferred approach for retrograde bypasses to this vessel provided that the occlusive disease is limited to its orifice (Figure 2). Alternatively, the SMA may be exposed through the lesser space at the caudal border of the pancreas or at the base of the mesocolon after caudal retraction of the transverse colon.

Management of Juxtarenal Aortic Occlusive Disease by Retroperitoneal and Transperitoneal Exposure of the Pararenal and Suprarenal Aorta

Transperitoneal Exposure of the Supraceliac Aorta and Celiac Artery

Transperitoneal Approach to Superior Mesenteric Artery and Pararenal Aorta

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Thoracic Key

Fastest Thoracic Insight Engine