Chapter 43 Management of Exacerbations in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Epidemiology

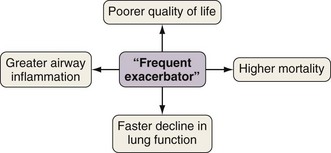

Exacerbations generally become both more frequent and more severe as the severity of the underlying COPD progresses. On average, patients with moderate to severe COPD, typical of those attending secondary care, will have one or two exacerbations requiring additional treatment annually. However, annual exacerbation incidence rates differ greatly among individual patients, and those prone to more frequent exacerbations experience a particular burden of disease (Figure 43-1). The best determinant of future exacerbation history is past exacerbation frequency, such that some patients appear more intrinsically susceptible and some more resistant to these important events.

Pathophysiology

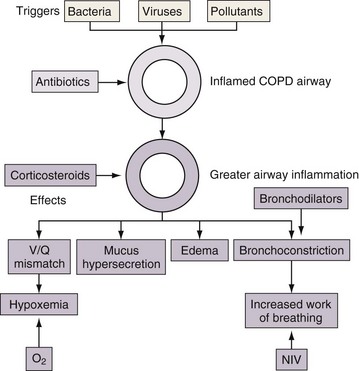

Defining the role of airway infection in causing COPD exacerbation is problematic. Recent advances in molecular biology have isolated respiratory viruses and potentially pathogenic bacteria from the airways of most patients during exacerbations (Box 43-1). However, certainly for patients with more severe underlying disease, bacteria also are often present in the stable state (bacterial colonization). Therefore the presence of an organism at exacerbation does not assume a role in causing that exacerbation. More recent studies suggest that a change in the colonizing bacterial strain may be the precipitating cause. However, not all strain changes are associated with exacerbation, and vice versa. Reflecting this, as discussed later, antibiotics are not of universal benefit during exacerbations. Rhinovirus is the most often identified viral pathogen, and thus exacerbations are more common during the winter months, when viral circulation in the community is higher. The role of atypical organisms such as Chlamydia and Mycoplasma species appears minimal.

Understanding the pathophysiology of exacerbations in COPD explains the rationale for the various therapies employed. Bronchodilators may be helpful for increased bronchoconstriction and hyperinflation, corticosteroids may reduce airway inflammation, and antibiotics may be appropriate in exacerbations caused by bacteria (Figure 43-2).

Diagnosis

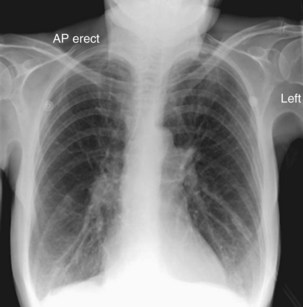

Although investigations are not helpful in the diagnosis of exacerbation, diagnostic tests help assess the severity of the presentation and exclude other conditions in patients with underlying COPD that may mimic or complicate exacerbation. Such diagnoses include pneumonia, pneumothorax, pulmonary embolus, and cardiac failure, and appropriate investigations include chest radiography, electrocardiography, oxygen saturation (SaO2) values, and arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis. Simple venous blood tests include complete blood count, urea and electrolytes, and C-reactive protein. A typical chest radiograph at exacerbation (Figure 43-3) should appear much the same as the patient’s radiograph in the stable state. Spirometry is not generally helpful because absolute values may be misleading, changes at exacerbation are small, and patients acutely dyspneic have difficulty performing the maneuvers. Sputum microscopy and culture may help to refine empirical antibiotic therapy in those not initially improving. For the patient with mild exacerbation responding to an increase in inhaled bronchodilators, it may be appropriate to omit further investigation.