Figure 8.1

After general endotracheal anesthesia is established, the endotracheal tube usually is placed beyond the tumor under bronchoscopic guidance in all but the most distal tumors. Airway obstruction should not be a concern, as it should have been dealt with previously if it was critical. Most patients undergo resection from the front, and this figure illustrates a cervicomediastinal exposure, which is probably the most common incision used. The patient’s head is placed and stabilized in a gel ring, and an inflatable bag is placed and inflated under the shoulders to extend the neck as much as possible. The neck and chest are prepared and draped in the usual sterile fashion. First, a low collar incision is made, then it is deepened through the platysma. Subplatysmal dissection is done superiorly to the thyroid cartilage and inferiorly to the clavicles. Gelpi retractors are placed to expose the wound. The strap muscles are separated in the midline, and the thyroid isthmus is divided at the top of the airway. The anterior wall of the trachea is exposed from the thyroid cartilage to the carina by incising the deep layer of the deep cervical fascia (the pretracheal fascia) and dissecting the loose areolar tissue in this plane, first with the scissors followed by a finger into the mediastinum. Next, a vertical T extension is made inferiorly by a partial upper sternotomy, typically down to the third rib. When dividing the sternum with either a saw or a Lebsche knife, one should finish the sternotomy by going to one side of the sternum into a rib interspace so that the sternum will spread easily. If exposure is challenging, it sometimes is helpful to transect the sternum horizontally at the third interspace level to allow maximal sternal spreading. A small sternal retractor is placed followed by a retractor in the mediastinal tunnel under the vessels to fully expose the airway. With a headlight and experience, one can learn to resect and reconstruct relatively distal tumors via this anterior approach. The sternotomy may be extended to a full sternotomy if bilateral hilar release is deemed necessary because of anastomotic tension. Usually, the outside of the trachea is relatively normal, so the proximal tracheal transection site is difficult to determine. A useful maneuver, shown here, is for an assistant to use a bronchoscope to aid in accurately localizing the extent of the tumor before an incision is made. A 25-gauge needle is used to pierce the trachea at the proposed incision site under bronchoscopic guidance, and the site may be marked with a stitch or sterile marker. This maneuver may be repeated for the distal site as well, minimizing “wasted” tracheal resection and tension on the reconstruction

Figure 8.2

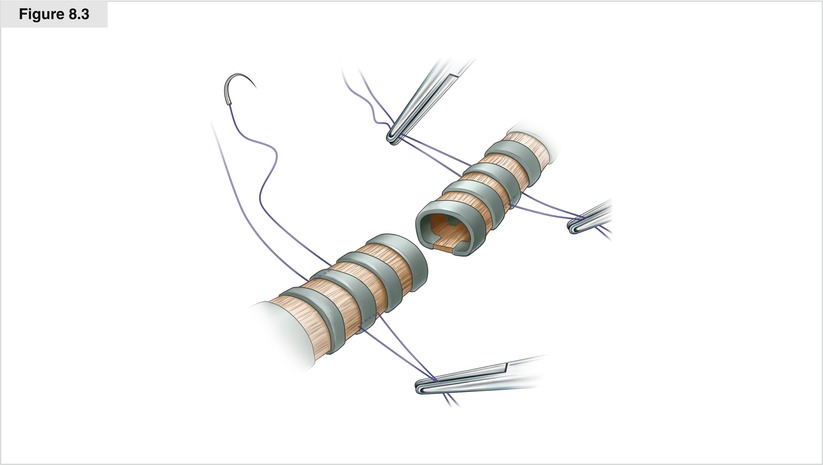

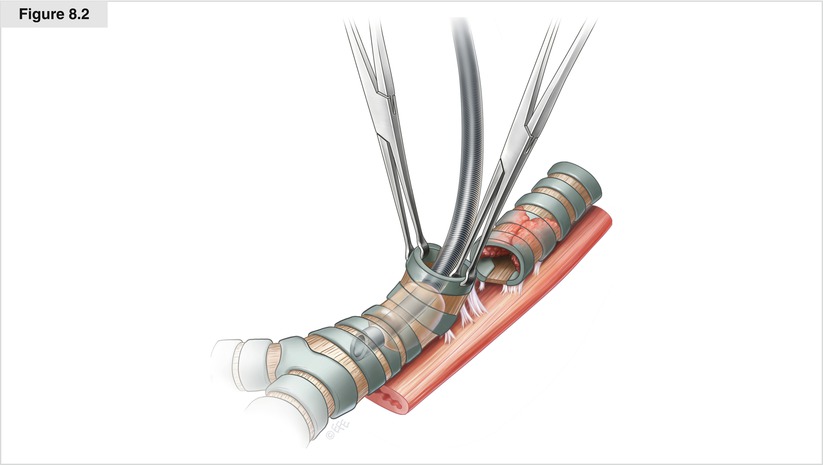

The trachea is dissected circumferentially over the length of the tumor and 7–10 mm beyond the proposed incision sites. Dissection is kept close to the airway laterally to avoid injury to the recurrent nerves. Care is taken when dissecting posteriorly to avoid entering the esophagus. If the posterior dissection is difficult, it is best to defer it until the airway is divided, when it becomes much easier to dissect. No attempt is made to radically resect paratracheal nodes, but adjacent nodes are removed if visible. To prepare for control of the airway once it is divided, a sterile endotracheal tube is placed on the field, with sterile extension tubing to connect it to the anesthesia machine. A final decision is made regarding resectability before the trachea is opened. If the portion requiring resection seems too large to allow comfortable reapproximation, one may reconsider and treat the tumor with radiation. This should be a rare occurrence, however, as the combination of CT and bronchoscopy allows a very accurate estimation of the length that needs to be resected. The cuff of the indwelling endotracheal tube is deflated before the trachea is cut. When the trachea is opened adequately, the endotracheal tube is pulled back to well above the proximal division site so it is out of the way. The on-field sterile endotracheal tube is placed in the distal airway as needed to ventilate the patient. If the esophageal muscle is invaded, it usually can be resected readily by cutting the muscle above the invasion site, finding the submucosal plane, and dissecting it to below the area of invasion. The trachea usually is held securely by two Allis clamps, one on either side of the cartilaginous rings. The esophagus usually is easy to dissect by elevating the trachea forward; furthermore, mobility is assessed readily by traction on the trachea. Also, one usually can further dissect anteriorly along the main bronchi under the main pulmonary arteries to gain additional release of the distal airway with the airway under tension with Allis clamps. The margins achieved depend on the pathology of the tumor and the extent of resection. Obviously, the goal is microscopically negative margins, although that is not always possible to achieve. Negative margins are hardest to achieve in adenoid cystic carcinoma, which has extensive submucosal and perineural spread. Tension always has to be weighed against margin status when deciding whether to resect more trachea. Essentially, grossly negative margins should always be achieved. When more trachea can be resected, if needed, separate margins should be sent for frozen section analysis. If the maximal amount of airway that can be resected is removed, there is little need for frozen section analysis of the margins, as the information received will not affect decision making in that case