Laryngomalacia. In laryngeal endoscopic visualization, the collapse of the arytenoid cartilage can be appreciated, occluding the lumen of the airway, in infant with persistent stridor

Laryngomalacia severity scale

Severity level | Respiratory symptoms | Feeding symptoms |

|---|---|---|

Mild | Inspiratory stridor when crying Saturation 98–100% at rest | Occasional cough or regurgitation |

Moderate | Inspiratory stridor Saturation ~96% at rest | Frequent regurgitation or feeding disorders |

Severe | Inspiratory stridor at rest Cyanosis, apnea, retraction Saturation ~90% at rest | Aspiration or poor growth increase |

A complete airway study is recommended in patients with LM associated with other serious symptoms, such as severe respiratory distress, growth impairment, cyanosis crises, apneas, possible deglutition or aspiration disorder, recurrent wheezing or pneumonias, and those patients with an underlying condition. In these cases, an association with another lower airway abnormality can be found in as many as 15% of the cases.

For those patients with LM and hypotony, neuromuscular disorders, or genetic syndromes, it has been suggested to complete the study with polysomnography, because of the increase in central apneas (in 46%), and echocardiography for those who also have heart congenital diseases, or suspicion of hypoxemia related to LM. Prognosis is good, and therefore a great percentage requires only clinical observation to support a spontaneous improvement in 75% of the cases, and an additional 15% to 20% improve when they reach 18 months of life. Those with persistent stridor at 2 years of age should also be endoscopically assessed. Up to 5% to 15% of cases may present serious obstructive symptoms and require surgery. Supraglottoplasty is the technique of choice, as well as an arytenoepiglottoplasty, to avoid chronic hypoxemia and eventual cor pulmonale. In surgery cases it is suggested to associate treatment to block acid reflux. Currently, tracheotomy has been displaced, and its indication is only when supraglottoplasty fails, or for an underlying condition.

Use of noninvasive ventilation would be an option for children with severe LM and respiratory distress, as well as obstructive sleep apneas waiting for a definitive surgical resolution.

Tracheomalacia/Bronchomalacia

Tracheomalacia. Endoscopic visualization of the intrathoracic trachea shows the collapse of the posterior wall moderately occluding the lumen (>60%), in an infant with Down syndrome, heart disease, and recurrent wheezing

Primary or congenital tracheomalacia , the most common congenital tracheal alteration, appears with a greater incidence in premature newborns. This alteration is attributed to tissue immaturity, but it is also associated to some genetic syndromes, or to disease that causes some alteration of the cartilage matrix or collagen fibers, such as mucopolysaccharidosis. TM is present in all the patients who have a tracheoesophageal fistula, or different degrees of esophageal atresia.

Because this is a defect in embryonic development, it would still be significantly present even after surgical repair. In primary cases not related to other diseases, the evolution of tracheomalacia is self-limited, normalizing close to the second or third year of life. Secondary TM is more frequent than the primary presentation, and it is predominant in males. It appears following a degeneration of the tracheal cartilage, because of prolonged intubation, tracheotomy, local injury (oxygen-caused toxicity, infections, ulcerations, or necrosis caused by local damage), or extrinsic prolonged compression (vascular rings, hypertrophy of the left atrium).

Its pathogeny is not clear, but it has been proposed that the following could be predisposing factors: genetic alteration in genes such as Sox9 and Shh, alteration in type I collagen, which is involved in the formation of the airway; or type II, which intervenes in the tension of the cartilage.

In histopathological terms, it has been observed that there is an imbalance between muscle and cartilage structure; the first one is predominant, whereas the second one is scarce. TM incidence is estimated as 1 in 1500–2500 children; this number would increase significantly if we only considered premature newborns. The most usual symptoms of TM are respiratory stridor and croup cough, which generally appear during the first weeks of life, and sometimes, in the mild cases, it is only present when there are viral infections. Stridor appears frequently, because of the collapse of the proximal area, when there is an increase in the pressure gradient caused by obstruction. Feeding disorders may appear, as well as increase of secretions in the lumen, or reflex apnea, in those patients in whom there is vascular compression. In TM and BM, a clinical history of recurrent wheezing, and atelectasis and recurrent ipsilateral pneumonias, are frequent. In severe TM and BM, airway obstruction may appear, as well as cyanosis during exacerbations. The most important action for the diagnosis is clinical suspicion after a careful anamnesis and physical examination, differentiating it from asthma, foreign body aspiration, and atelectasis caused by a different entity, among other possibilities. If the newborn is premature, or there are genetic syndromes, heart diseases, or neuromuscular disorders, this entity must be suspected.

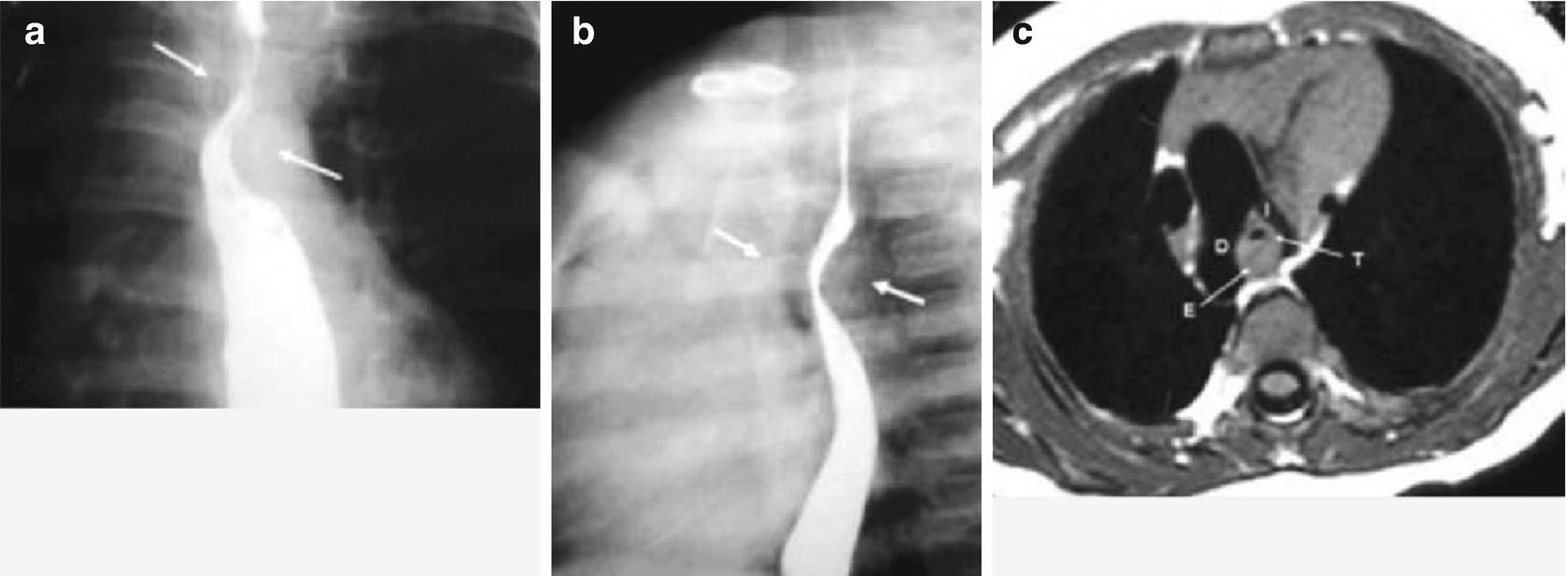

Imaging studies can be very useful, as, for example, the evaluation using contrast agents in fistulas, esophageal atresia, or vascular rings. In tracheomalacia, high-resolution computerized tomography (HRCT) can show slides and reconstruction of the airway, as well as showing the defect. Ideal diagnosis is done through a dynamic evaluation of the airway under pseudo anesthesia and spontaneous breathing, with a bronchial endoscopy. In older children, suspicion starts when a spirometry has a fluctuant obstruction in the air flow, namely in the flow/volume curve (inspiratory or expiratory branch, depending of the case). In an important percentage of patients with TM and BM, the disease spontaneously progresses to its resolution during the first 2 years of life. The recommendation is to avoid viral infections and inappropriate treatments. Chest physiotherapy is suggested for patients with ineffective cough, atelectasis, or abundant secretions. Use of bronchodilators is controversial, as a reduction in the muscle tone would favor airway collapse, although the role that the bronchospasm may have in the airway must be considered.

In the most severe cases, or those who do not improve, according to the experience of the centers, they can be managed with continuous positive pressure in the airway (CPAP), tracheotomy, and mechanical ventilation. A surgical treatment can also be considered for those who have presented vital risk or no resolution, such as aortopexy, tracheopexy, resection, and tracheal reconstruction with cartilage implants. Use of stent support tracheal devices (metallic or silicone) has been shown to be effective, and they would be useful in the short term, but they are related to other important complications: granulomas, tearing, bleeding, etc. The stents are indicated after other techniques have failed, and it has been suggested to use preferentially those that are auto-expandable and thermoplastic.

Tracheal Stenosis

Tracheal stenosis is a very infrequent disease. The trachea is characterized by the presence of approximately 20 cartilages along its length, which can range from 5.5 to 8 cm, from birth to 2 years of life. These cartilages support the lumen of the respiratory airway, but they are not complete in the posterior tracheal segment, where the membranous section is located. Tracheal stenosis is characterized by a reduction in the tracheal lumen in diverse diameters and lengths, caused by the presence of complete tracheal rings and the absence of the membranous section in the smooth muscle fibers, which may be congenital or acquired. Three types of lesions have been described: segmental stenosis with variable length, hourglass stenosis, and funnel stenosis, as well as generalized tracheobronchial hypoplasia. It is difficult to estimate its incidence, and it varies among different centers. It has been reported that the congenital tracheal stenosis rate is about 10% and the rate of acquired stenosis is 90%, secondary to prolonged intubation (75–90%), trauma, connective tissue diseases, neoplasia, or idiopathic causes. Clinical manifestations are variable and depend on the degree of severity, newborn respiratory distress, cyanosis, persistent or recurrent inspiratory stridor with prolonged progression, recurrent wheezing, atelectasis, and pneumonia. In other cases, the diagnosis has been suspected in children who have undergone an early surgery in their life and weaning has not been successful.

Recently, a review of approximately 310 children showed that there is predominance in the masculine gender and that almost half the children affected have some associated comorbidity. The most common comorbidities were pulmonary artery ring, defects in the ventricular septum, defects of the atrium septum, persistent arteriosus ductus, lung agenesis, Fallot tetralogy, and aortic restriction. A minority had associated genetic syndromes. This diagnosis is proposed for children with persistent wheezing, or ‘seal cough’ associated with compatible X-rays. Definitive diagnosis is through tracheal endoscopy, which allows visualizing the obstruction, its diameter, and degree of compromised length. Chest HRCT with airway reconstruction gives a better characterization of the lesion and helps to decide the type of corrective surgery. In some cases, if other malformations are suspected, a magnetic resonance image (MRI) may be requested as a complement. In older children, a spirometry presenting a fixed obstruction in the intrathoracic airway in the flow–volume curve strongly suggests tracheal stenosis.

Treatment may be conservative for mild or moderate cases, where there is no early respiratory distress, extubation failure, or poor growth, and the follow-up can be made through endoscopy during the first 2–3 years of life, but its resolution is usually surgical. Tracheoplasty may be considered, resecting the stenosis area and using end-to-end anastomosis for small lesions. However, in children with tracheal compromise, in whom more than 50% of tracheal length is compromised, a slide tracheoplasty may be needed, as well as the interposition of cartilage, thus widening the tracheal lumen in critical situations.

Vascular Rings

Vascular rings (VR) are congenital anomalies of the aortic arch and its branches that cause tracheal or esophagus compression, or both. They are infrequent, and their incidence is not clear, but they have been estimated to be about 1–3% of the congenital cardiovascular anomalies. They are classified as complete and incomplete VR. The most common ones are the complete ones, which in almost 90–95% of the cases are represented by the double aortic arch (DAA) and its subtypes (right dominant arch, left dominant arch, balanced arch), and right aortic arch (RAA) and its subtypes (RAA and left aberrant subclavian artery, and RAA+ and mirror vessels pattern). The most frequent complete ring is DAA, at about 75–90% of all, and second in place is RAA, at about 12–25%. Incomplete vascular rings do not form a complete ring around the trachea and the esophagus, but they do compress them. These rings are represented by innominate artery compression, pulmonary artery ring, and left aortic arch (LAA), with right aberrant subclavian artery. It is thought that this last entity is subdiagnosed or its diagnosis is done late, as it tends to be asymptomatic. In 38% of cases it is related to Down syndrome. An aberrant innominate artery represents 10% of the VR, and compresses the trachea through its anterior surface; it presents more symptoms if it is related to tracheomalacia or esophageal atresia, when there is no dysphagia. A pulmonary artery ring is commonly associated with a full cartilage ring, which determines the greatest cause of mortality caused by VR, and it is related to tracheobronchial alterations, such as TM, hypoplasia, or tracheal stenosis, as well as being related to heart diseases such as persistent arteriosus ductus, or ventricular or atrial communications. Sometimes VRs have been reported as associated with other congenital malformations, such as kidney (agenesis, ectopy, horseshoe kidney), tracheoesophageal fistula, hiatal hernia, diaphragmatic eventration, imperforated or ectopic anus, PHACE syndrome (posterior cranial fossa alteration, facial hemangioma, alteration of brain, cardiovascular, and eye arteries), and some genetic syndromes, such as trisomy 21, deletion 22q11.

VRs frequently present symptoms early in life, which depend on the type and degree of compression of the clinical manifestations. Usually VR appear with stridor, persistent cough, respiratory distress, or dysphagia, especially with solid foods (late symptom). Cough has been described “like a seal,” or tracheal, with a metallic tone, and it is very noticeable when there are unimportant respiratory infections. Stridor is generally biphasic, but it can appear as only one sound during expiration, which is monophonic and persistent and should be called wheezing. All symptoms tend to increase with crying, feeding, playtime, or respiratory infections. Respiratory symptoms are present in 70% to 97% of all the children, according to several studies, and they may cause a poor growth. Less frequently, and only when there is a significant tracheal compression, it may appear during the newborn period with respiratory distress, suprasternal and costal retraction, tendency to cervical hyperextension, cyanosis, reflex apnea, and extubation failure. The VRs that present more symptoms are the DAA and the RAA, caused by early tracheal compression, although the aberrant subclavian artery may also be evident, because of the posterior esophageal compression, which appears later.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree