Chapter 67

Lymphedema

Nonoperative Treatment

Andrea L. Cheville, Gail L. Gamble

Based on a chapter in the seventh edition by Gail L. Gamble

Lymphedema remains a frustrating and complex management challenge for clinicians and patients alike. The pathophysiology and diagnosis of lymphedema are thoroughly reviewed in Chapter 13. Chronic lymphedema can engender functional morbidity and adverse symptoms that degrade patients’ quality of life (QoL).1 Despite remarkable advances in the molecular, genetic, and clinical understanding of this condition, lymphedema remains incurable.2,3 Fortunately, a majority of patients respond to conservative treatment, and their lymphedema can be indefinitely temporized. Nonsurgical management options fall into three categories: (1) preventive measures for at-risk patients; (2) risk reduction strategies for patients with established lymphedema; and (3) manual therapies to reduce and temporize established lymphedema. Pharmacologic treatments have little role in conventional lymphedema management. However, because they continue to be widely used, and because they may benefit patients with mixed etiology edema, they are outlined in this chapter. Lymphedema may engender profound dysmorphism, adversely affecting patients’ self-image, social roles, and QoL; therefore, approaches to address the psychosocial dimensions of lymphedema are also addressed.2–6

Preventive Measures for At-Risk Patients

Primary Lymphedema

A majority of patients who develop primary lymphedema have no family history of lymphedema or awareness of abnormal lymphatic development before the onset of swelling; thus, proactive measures cannot be used to prevent lymphedema. Recent advances in genetic mapping and the identification of mutations for primary disorders, such as the hereditary form of lymphedema (Milroy’s disease), or other disorders (lymphedema-distichiasis)6,7 now offer the possibility of genetic testing for potentially at-risk family members. Both genetic testing and counseling regarding early protective measures are available in a number of medical centers and may become more widespread in the future.

Patients with unilateral primary lymphedema should be counseled to minimize risk factors that may trigger the development of lymphedema in the contralateral limb or other areas of the body.

Secondary Lymphedema

Secondary lymphedema develops from the traumatic, infectious, or iatrogenic compromise of an intact lymphatic system. In the developed world, secondary lymphedema occurs as a result of clinical efforts to stage or treat cancer, most commonly surgical lymphadenectomy and/or the radiation of lymph node beds. The extent of lymphatic damage can be quantified in the number of lymph nodes removed and the radiation dosage, allowing for risk stratification. Patients at higher risk can be instructed in preventive strategies.

Recent efforts to modify cancer treatments to spare lymph nodes have proven extremely effective. For example, the shift from 2-3 level axillary lymph node dissection to sentinel lymph node biopsy, followed by completion dissection only if nodal metastases are detected as the standard of care, has reduced lymphedema incidence by approximately 80%.7–9 Similarly, the use of sentinel lymph node biopsy procedures to identify lymph nodes involved by metastatic melanoma has significantly reduced the requirement for extensive inguinal and pelvic lymphadenectomy, with a resultant decrease in lower extremity lymphedema.10 Novel techniques have also been developed to minimize the incidental, nontherapeutic radiation delivered to axillary lymph nodes critical for arm drainage, although these are not yet widely available in conventional practice.11 However, it is essential to bear in mind that, to date, no lymph node sparing technique eliminates the risk of lymphedema. Therefore, following lymph node removal or irradiation, early patient education regarding skin precautions and appropriate exercises may reduce the incidence of lymphedema.12

Worldwide, infestation by the parasite Wuchereria bancrofti is the most frequent cause of lymphedema. W. bancrofti is endemic in tropical climates.8 There has been much activity directed toward the control of filariasis in recent years.9,10 Programs have been developed to reduce vector transmission (decreased transmission of W. bancrofti and Brugia malayi parasites by mosquito bites) and to administer antifilarial drugs to at-risk populations.13 The mass administration of diethylcarbamazine plus ivermectin significantly decreases lymphatic filariasis.9 Recognition that the endosymbiotic bacterial organism Wolbachia may also play a role in the development of filarial lymphedema has spurred investigation into the utility of other drugs for filariasis control.10,14 Clearly, management of this difficult issue must be aimed at public health measures.

Other forms of chronic infection can cause sufficient inflammation to damage lymphatics, undermine the system’s functional capacity, and eventually, cause lymphedema. Recurrent cellulitic infections may cause permanent irreversible lymphatic compromise.14 However, because lymphedema is the strongest risk factor for cellulitis,15,16 it can, at times, be difficult to distinguish whether cellulitis simply reflects the initial presentation of previously subclinical lymphedema or independently causes lymphedema. The low-grade chronic inflammation produced by rosacea has been implicated in causing lymphedema of facial structures, particularly the eyelids.17

Healthy Lifestyle: Activity and Diet

Exercise, particularly walking and aerobic exercise, promotes lymph flow through a number of mechanisms, including an increase in sympathetic tone (Box 67-1). Historically, patients at risk for developing lymphedema have been advised against “overusing” their at-risk body parts for fear of triggering lymphedema. This recommendation is based on anecdotal associations of the initial onset of lymphedema with episodes of vigorous exercise or sustained, repetitive use of the at-risk extremity. Blanket recommendations against exercise have recently been tempered and re-framed based on the results of several adequately powered randomized controlled trials.18,19 These trials revealed that a gentle, incremental program of full-body resistive training, begun at a low level and increased gradually, did not increase lymphedema incidence among breast cancer survivors at-risk of developing lymphedema, and might actually be protective. Similar trials have not yet shed light on the risk-benefit profile of exercise in lower extremity lymphedema.

Various dietary restrictions have been advocated, but few have empirical support apart from avoidance of excessive salt intake. One study suggested that lowering triglyceride levels may offer benefit.20 Obesity unquestionably worsens lymphedema,21,22 and weight reduction augments the effects of other measures for edema reduction.23 Therefore, dietary moderation and weight management are integral to lymphedema prevention. Nutritional supplements, apart from protein supplementation in hypoalbuminemic patients, have not been subject to rigorous scrutiny; therefore, their use should not be endorsed as a credible lymphedema prevention strategy.

Skin Hygiene

Attention to daily skin hygiene of the at-risk limb is imperative (Box 67-2), yet this is often challenging for patients who have medically complicated obesity17 and/or osteoarthritis, or who lack social support and resources. The limbs should be washed regularly with soap and water, and while still moist, lubricated with an alcohol-free emollient cream to trap moisture, thereby minimizing the risk of microfissures. Patients with a history of fungal infection, including candidiasis and tinea, should use topical antifungal medications. Routine use of topical clotrimazole cream (1%) or miconazole nitrate lotion or cream (2%) is sufficient for most patients. Oral fluconazole or itraconazole may be needed for recalcitrant or extensive infection. No studies have definitively addressed the efficacy of these treatments in terms of documenting a decreased incidence of lymphedema.

Prophylactic Compression

The use of prophylactic compression has been endorsed as a preventive strategy for provocative situations that may theoretically trigger an increase in lymph production (e.g., air travel and exercise). Air travel, presumably due to reduced ambient pressure, has been anecdotally linked to the initial onset of lymphedema.24 The rationale for the use of prophylactic garments is their theoretical potential to minimize transient, situational increases in lymph production. Notably, no empirical data support their use, and poorly fit garments may actually increase patients’ risk of lymphedema by applying intense focal pressure and creating a tourniquet effect. Therefore, if a patient’s elevated risk of developing lymphedema seems to warrant use of a prophylactic garment, an experienced fitter should determine garment type and size, and compression should not exceed 15 to 20 mm Hg.

The benefits of “prophylactic” compression may be substantially increased among patients who develop mild swelling or symptoms that suggest the presence of incipient lymphedema. For example, a report described the use of upper extremity compression sleeves among breast cancer survivors whose arm volumes increased by 3% over their preoperative baselines.26 Normalization of arm volumes was achieved for a majority of patients after 4 weeks of sleeve use and was maintained for an average follow-up of 4 months. At 1 year following diagnosis, lymphedema incidence was reduced relative to reported rates.

The decision to use prophylactic compression is inevitably highly individual. The pros and cons must be carefully weighed, ideally by a patient in concert with their physician. Sometimes, if feasible, consultation with a lymphedema specialist may be of benefit. Educational materials to assist in decision making are available through patient advocacy groups, such as the National Lymphedema Network and the American Cancer Society in the United States.

Minimize Infections

New evidence suggests that some patients may be predisposed to developing cellulitis by virtue of preexisting, subclinically impaired lymphatic drainage.27 A study that performed bilateral lymphoscintigraphies on 33 patients after limb cellulitis detected lymph flow impairment in the limb affected by cellulitis, as well as in the nonaffected limb. Prompt antibiotic control of even minor infection may therefore be effective in preventing clinical lymphedema.

Practical Management and Risk Reduction Strategies for Established Lymphedema

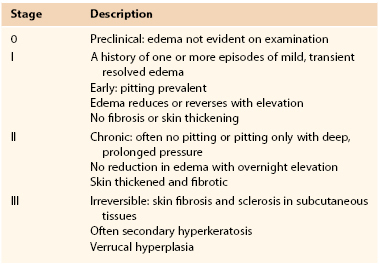

The relative effectiveness of all management strategies hinges on a patient’s lymphedema stage. Lymphedema is divided into four stages (Table 67-1) based on the presence of intersitial fibrosis and dermal metaplasia.48 Consideration has led to the recent addition of stage 0, a preclinical stage of lymphedema that may justify insurance coverage for treatments directed toward limbs at risk.28 A growing, although still tenuous, evidence base suggests the utility of addressing very early (preclinical) volume change.25,26,29

It should be noted that affected body parts generally have regions with different stages of lymphedema. For example, a patient with lower extremity lymphedema may have stage III lymphedema (distinguished by dermal keratinization and papilloma formation in the foot and ankle region), stage II lymphedema of the calf, and stage I lymphedema of the thigh. Generally, a body part is assigned the most advanced lymphedema stage among all its involved areas. Patients may be assigned a different stage for each affected body part. Lymphedema staging is integral to clinical decision making and communicates useful information regarding a patient’s likely treatment responsiveness, risk of progression, and propensity to develop complications.

Any comprehensive lymphedema treatment program should include standardized measures of limb size and volume to monitor the response to treatment. Changes in limb size have been followed using objective measures, including circumferential measurements obtained at predetermined measurement intervals (e.g., 10 cm) from an anatomic landmark, or volumetric assessments using water-displacement or computed volumetric techniques.26 Newer methods using bioelectrical impedance analysis30 have been reported. Bioimpedance is growing in popularity as a means to monitor the limbs of breast cancer survivors at risk for lymphedema. Ultrasound is used in the research setting to measure dermal saturation that correlates with whole limb edema,31,32 and may become a more viable clinical tool in the future for measuring focal edema and edema effecting nonlimb body parts (e.g., breast, trunk, genitalia, etc.). Additionally, an infrared optoelectronic device for measuring both upper and lower extremity volumes has been validated and is in clinical use at larger lymphedema centers in the United States and Europe.33,34

Elevation

Elevation is the simplest way to reduce early, stage I lymphedema.35 The optimal degree of elevation has not been the subject of research. Thirty to 45 degrees is sufficient, although as little as 5 degrees of elevation, if maintained for a sufficient interval, offers meaningful benefit. Prolonged elevation was used for decades and is still used for early reversible lymphedema or for refractory cases as part of combined therapy. Lymphedema reduced through elevation must subsequently be managed with an adequate compression system; otherwise, all volume reduction will be lost. Today, in-patient treatment is a rare option, and patients often find elevation therapy outside the hospital impractical, and thus, ineffective. Also, growing appreciation of the importance of exercise and the preservation of muscle bulk and tone in lymphedema management has highlighted the downsides of the inevitable physical deconditioning that occurs with prolonged elevation. O’Donnell and Howrigan have suggested that 4- to 6-inch blocks be placed under the legs of the foot of the bed to provide adequate overnight elevation for patients with lower extremity edema.36 A foam wedge also offers an inexpensive and comfortable means of limb elevation (Fig. 67-1).

Antibiotics

Prompt administration of appropriate antibiotic therapy to any patient with lymphangitis and/or cellulitis is essential.19,37 The pathogen responsible for limb cellulitis is usually a β-lactam–sensitive group A streptococcus. Staphylococcus species and other organisms are less commonly reported.19 At the first sign of cellulitis, antibiotic treatment, such as oral penicillin VK, 250 or 500 mg four times a day, should be initiated. Other β-lactam antibiotic therapy, a simple cephalosporin (e.g., cephalexin), or a macrolide (e.g., erythromycin, azithromycin) can be used. Intravenous antibiotic infusion, hospitalization, and bed rest with limb elevation may be needed for some patients with more severe lymphangitis and/or cellulitis. Antibiotic therapy should be continued for 7 to 14 days until all signs and symptoms of acute infection have clearly resolved. There is no consensus in the literature on the optimal treatment of recurrent cellulitis, with or without previous lymphedema. When spontaneous episodes occur more often (usually more than two to four times per year), a regular prophylactic program—penicillin VK (or an equivalent) 250 mg four times a day for 7 days of each month—can be considered. An alternative regimen of penicillin given intramuscularly once a month in patients at increased risk for cellulitis has not been effective in reducing infections.31 A definitive antibiotic prophylaxis regimen for patients who experience recurrent cellulitis has not yet been identified. For some patients, an intermittent prophylactic program may not be sufficient to prevent recurrent infections, and a daily antibiotic regimen may be needed.19 Manual decongestion with maintained volume reduction significantly reduces the incidence of lymphedema-related lymphangitis and/or cellulitis.

Mechanical Reduction of Limb Swelling

Complex Decongestive Therapy

Complex decongestive therapy (CDT) is a comprehensive lymphedema reduction program that combines elevation, “remedial” exercise, manual lymphatic drainage massage, and compression wraps, and represents the current international standard of care.38,39 CDT, or highly related programs, popularized in Europe by Földi et al,40 Kasseroller,41 and Leduc et al,42 as well as Casley-Smith43 in Australia was introduced to the United States in the early 1990s and continues to be first-line therapy for stage II and III lymphedema. CDT’s success has been documented worldwide.44–47,48 The program involves two phases, each with four discrete components (Box 67-3). Although very successful, it is a resource-intensive treatment that requires a large investment of both the therapist’s and patient’s time. Therapists must be specially trained to perform standardized techniques of manual lymph drainage and complex multilayered wrapping. This treatment is currently offered in specialized practices, but these lymphedema programs are becoming more widely available. In the United States, there is a voluntary certification process that involves the documentation of training and treatment hours, and a certifying examination to ensure competence. This effort was initiated and continues to be coordinated by the Lymphology Association of North America (LANA). Certified therapists are listed on LANA’s website (http://www.clt-lana.org), which can be searched by name, state, or zip code.