Figures 24.1 and 24.2

Median sternotomy, VATS. A complete median sternotomy is performed in apnea. Because emphysema patients often do not have any retrosternal fat, there is a high risk of injury to the mediastinal pleura or to the lung itself with the saw. After the retractor is opened, both mediastinal pleurae are incised carefully without cutting into the lung. Single-side ventilation is helpful in this situation. At this point, the anesthetist is asked to apply transbronchial suction to remove secretions and support collapse of the lung. Because of potential problems regarding bone healing, sternotomy has lost its importance; most operations today are actually performed by VAT. Endoscopic LVRS is performed through the fourth or fifth intercostal space. It is preferable to perform the utility thoracotomy first and palpate to rule out adhesion before introducing the ports and video camera. Bullae or the thin-walled lung are at high risk for injury. If the lung does not collapse and the overview is incomplete, it is better to use a small retractor and to insert the stapler under direct view than to risk injury to the remaining lung

Special Aspects

Because the end-stage emphysema patient has no reserve to compensate for problems, the paramount goal is to prevent major side effects. LVRS-specific side effects are pain and reduced clearance of bronchial secretions. The most common complications are air leakage, pneumonia, and myocardial problems. Therefore, postoperative pain management is essential, especially because there is an inverse relationship between respiratory function, respiratory complications, and pain (Boley et al. 2012). Regardless of surgical approach, each patient should be offered a peridural catheter for pain control.

Prolonged air leakage longer than 7 days was documented in 90 % of the NETT trial patients (McKenna et al. 2004, Criner and Sternberg 2008), illustrating the fragility of the emphysematous lung. To avoid prolonged air leakage, special care is needed. Buttressing staple lines, the generous use of sealants (Figs. 24.4 and 24.6) and preparation of a pleural tent (Fig. 24.5), as well as the application of low suction (−10 cm H2O) postoperatively, are effective measures. Greater incremental improvement after bilateral LVRS is accompanied by a more rapid rate of decline later. Unilateral LVRS, followed by a second, contralateral resection if significant deterioration in symptoms occurs, might be beneficial for a longer period (Teschler et al. 1999).

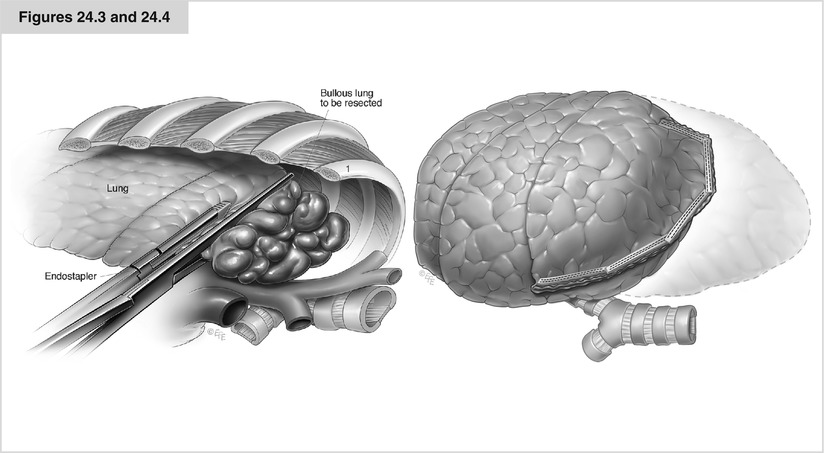

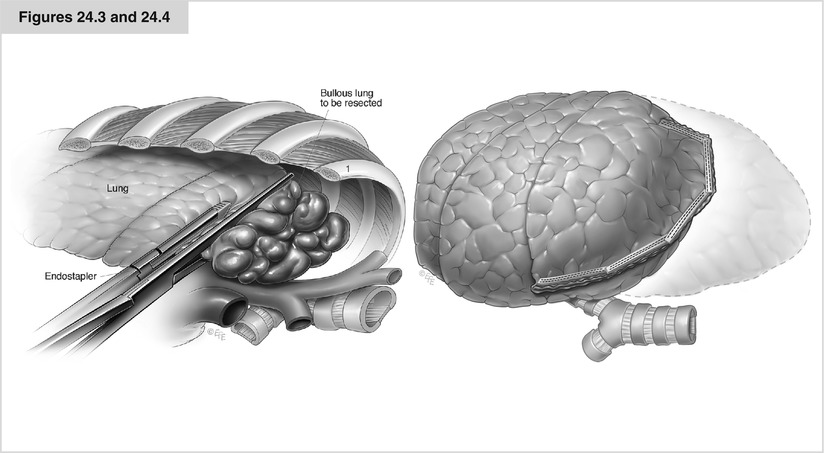

Figures 24.3 and 24.4

Horseshoe resection, stapler, buttressing. The stapling line starts at the incision and continues over the top and down to the back side of the lung like a horseshoe including the most affected parts of the upper lung. The stapling line is best fixed in healthier lung with substantial tissue; therefore, the goal is to proceed directly along the border between healthy and diseased tissue, completely removing the latter while preserving as much of the former as possible. If the identified region to be resected does not collapse, it is best to use conventional linear and buttressed staplers instead of endostaplers. The separate application of each side of the stapler allows correct positioning and finally compression of the emphysematous lung in between. Alternatively, one may try to compress the planned resection line with a straight long DeBakey clamp (Figs. 24.4). It is crucial to set the next stapling line exactly where the first line ended. When air leakage does occur, suturing of the lung is necessary; thereby, all stitches must include buttressing material on both sides for stability

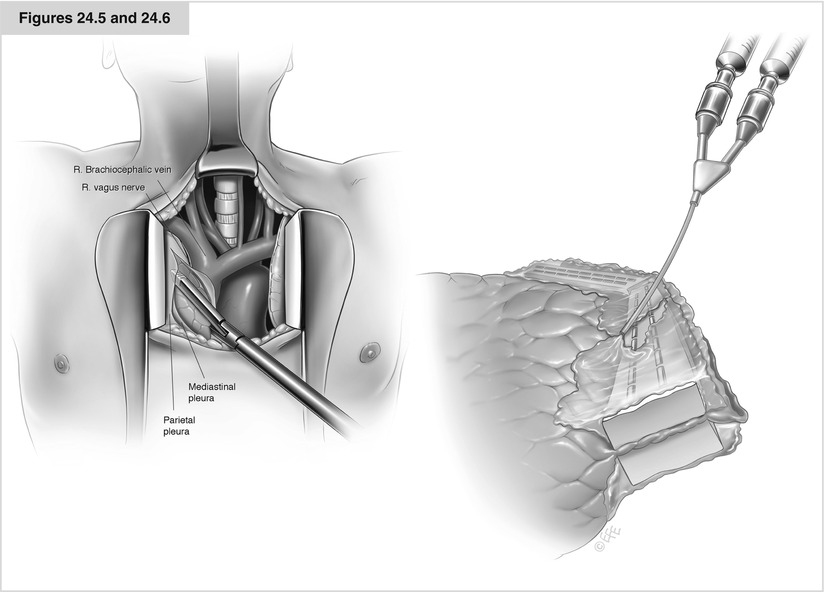

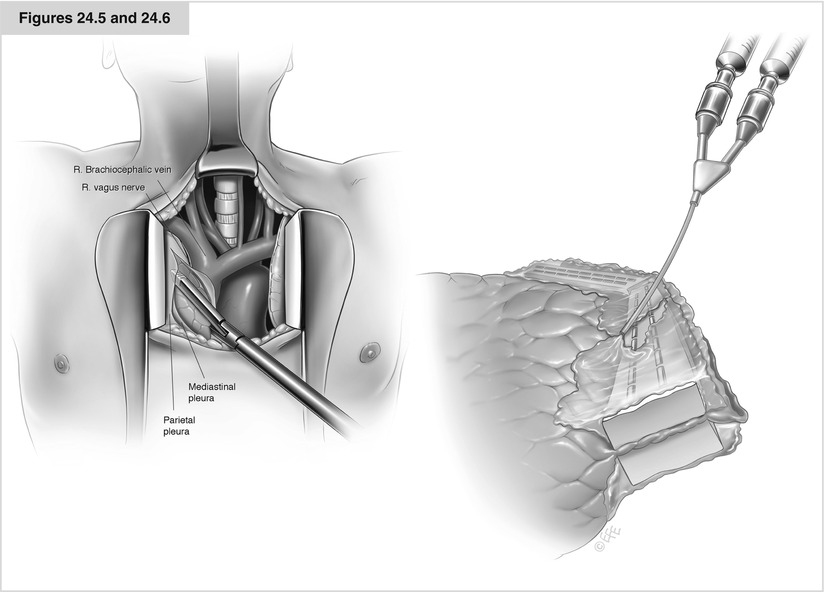

Figures 24.5 and 24.6

Pleural tent, fibrin glue. Because air leakage may arise hours or days after surgery, despite a normal water probe at the end of the procedure, it sometimes is beneficial to use sealants to stabilize the stapling line and even to occlude the channels of the metal clamps. Furthermore, patients must be instructed to avoid any activity that highly increases intrapulmonary pressure. Whenever a small air leak persists at the end of the procedure or a large apical space remains, it is advisable to prepare a pleural tent. As a consequence of corticoid medication, the parietal pleura often is very fragile and must be released with caution. The extrapleural space fills with blood and pleural fluid after several hours or days, and the pleural tent builds a “second skin” over the visceral pleura

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree