Chapter 139

Lower Extremity Aneurysms

Glenn Jacobowitz, Neal S. Cayne

Based on a chapter in the seventh edition by Frank B. Pomposelli and Allen Hamdan

Aneurysms occurring in the arteries of the lower extremity are second in frequency only to aneurysms of the infrarenal aorta and iliac arteries. Historically, lower extremity aneurysms were typically mycotic, syphilitic, or traumatic in origin. However, most aneurysms in the femoral, popliteal, and tibial arteries are currently either degenerative aneurysms or post-traumatic pseudoaneurysms related to catheterization or instrumentation. True aneurysms occur far more commonly in men than women, at a ratio of 30 : 1.1,2 Furthermore, true aneurysms of the femoral or popliteal arteries are often associated with aortic aneurysms and aneurysms in the contralateral lower extremity. The association with aortic aneurysms ranges from 50% to 90% for femoral aneurysms,2–6 from approximately 30% to 50% for popliteal aneurysms, and as high as 70% for bilateral popliteal aneurysms.1,2,7,8 Bilaterality is also common, occurring in approximately 25% to 50% of femoral aneurysms and 50% to 70% of popliteal aneurysms.2–4,7,9 Conversely, up to 14% of men with aortic aneurysms have been found to have femoral or popliteal aneurysms, but this combination is a rare finding in women.6 Additional imaging, such as duplex ultrasound (DUS), may therefore be indicated to evaluate for concomitant aneurysmal disease when an aortic or lower extremity aneurysm is diagnosed.

Aneurysms in the lower extremity are of clinical significance because of their potential to cause limb-threatening ischemia. More rarely, such aneurysms can rupture, particularly false aneurysms of the common femoral artery. Treatment is preferable when they are asymptomatic; hence the importance of detection and a thorough knowledge of the association with other aneurysms. Symptomatic true aneurysms have a much higher incidence of limb loss because of the prevalence of embolization of thrombus from within the aneurysm sac to more distal arteries. Clinicians must always consider embolization from an aneurysm when evaluating lower extremity ischemia and when planning interventions. There have been significant changes in the treatment of lower extremity aneurysms along with additional treatment options, including various endovascular therapies.

Femoral Artery Aneurysms

Femoral artery aneurysms occur primarily in the common femoral artery and less commonly in the profunda femoris and superficial femoral arteries. The common femoral artery (CFA) can be the site of true aneurysms and of pseudoaneurysms related to prior instrumentation or previous revascularization procedures. True aneurysms are less common and are often associated with popliteal artery and aortic aneurysms.10 In any artery, an aneurysm is defined as a focal, fusiform dilatation of the artery to 1.5 times the normal diameter of the adjacent segment of artery.11 The normal size of a CFA in men is approximately 1.0 cm and 0.8 cm in women.12 Repair has been considered clinically indicated for aneurysms more than 2.5 cm in diameter.13

Pseudoaneurysm of the CFA usually appears as a saccular outpouching of the vessel and has a narrow neck representing a defect in the vessel wall due to instrumentation. The pseudoaneurysm is actually a rim of fibrous tissue containing thrombus and arterial flow in continuity with a defect in the CFA. Iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms are addressed separately from true aneurysms.

True Aneurysms

Epidemiology

In a large study of true aneurysms of the femoral arteries, 57% were in the CFA, 26% in the superficial femoral artery (SFA), and 17% in the profunda femoral artery (PFA); 26% were bilateral and 48% were associated with additional aneurysms.10 They are found predominantly in older men (70 years or older) and are associated with smoking and hypertension.3 The majority are degenerative, but they have also been reported with arteriomegaly and other conditions such as Behçet’s disease, Parkes Weber syndrome, and Wegener’s granulomatosis.14–19

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Isolated true femoral aneurysms are asymptomatic in 30% to 40% of patients and are often found on physical examination or DUS scan. Another 30% to 40% cause localized pain and tenderness or compressive symptoms resulting in neuropathic pain or leg edema. The most common presentation in up to 65% of cases is lower extremity ischemia, including claudication or critical ischemia resulting from embolization.2,3,10 Rupture is a rare occurrence—occurring in approximately 4% of cases.20 Duplex ultrasound is the modality of choice for diagnosis and assessment of femoral artery aneurysms. It is cost effective and accurate. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) can also be used and may be of additional value in the planning of endovascular repair and when specific measurements are needed to identify normal artery proximal and distal to the identified aneurysm. CTA and MRA can also be useful to look for additional aneurysms such as aortic, iliac artery, contralateral femoral artery, and popliteal artery aneurysms (PAAs).

Indications for Treatment

All symptomatic femoral aneurysms should be treated to prevent embolization, thrombosis, worsening of local compressive symptoms, and rupture. Although the natural history of asymptomatic femoral artery aneurysms is unclear, it is often suggested that repair of asymptomatic femoral aneurysms more than 2.5 cm diameter is indicated in “good-risk” patients.13 This suggestion is based on one of the largest reported series of 172 femoral aneurysms in 100 patients; 40 were asymptomatic, and 105 small (<2.5 cm) aneurysms were managed nonoperatively.2 Of this nonoperative group, limb-threatening ischemic symptoms developed in only 3 patients over a period of 28 months. Surprisingly, the mean diameters of symptomatic and asymptomatic aneurysms were identical, at 2.8 cm. Smaller asymptomatic aneurysms can be managed conservatively with surveillance using DUS and do not typically require intervention unless they expand or become symptomatic.2,10,13

Surgical Treatment

Treatment of CFA true aneurysms usually consists of open repair, in which the aneurysm is excluded with an interposition graft. To prevent injury to surrounding structures that may be adherent to it, the aneurysm sac is usually not resected. The preferred graft material is synthetic, either polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) or Dacron.3,10,13 The prosthetic grafts are better size matches and have equivalent or better patency rates than vein grafts in this positon.3 Preoperative assessment of the aorta and the iliac, superficial femoral, and popliteal arteries should be performed to detect additional aneurysmal disease. In both elective procedures and emergency procedures for rupture, open repair can be achieved with minimal morbidity and excellent long-term patency.3,10,13 Proximal control can usually be achieved with a clamp on the distal external iliac artery or proximal CFA via a longitudinal groin incision. In cases of large aneurysms, proximal control can be achieved with balloon occlusion placed via the contralateral femoral approach. If this is not possible, a suprainguinal retroperitoneal exposure of the external iliac artery may rarely be required to obtain proximal control of a large, proximal CFA aneurysm.

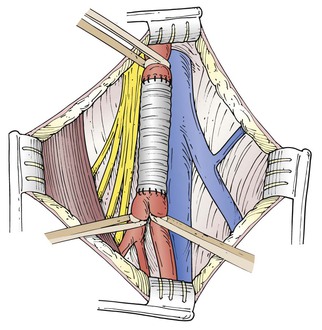

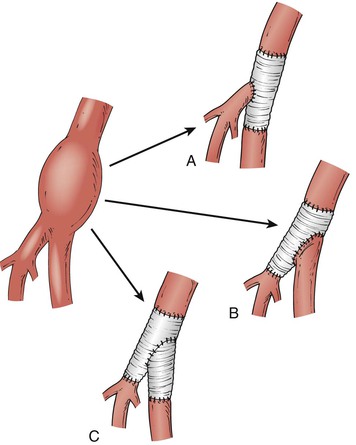

An aneurysm confined to the CFA can be treated with a short interposition graft (Fig. 139-1). An aneurysm extending into the PFA or SFA requires more complex reconstruction with an interposition graft from the proximal CFA to the PFA or SFA, and a jump graft to the other femoral branch (Fig. 139-2). It is important to preserve flow to the PFA to prevent future severe ischemia.13

Figure 139-1 Surgical repair of an aneurysm confined to the common femoral artery can be accomplished with a simple interposition graft. (From Ouriel K, et al, editors: Atlas of vascular surgery, Philadelphia, 1998, WB Saunders.)

Figure 139-2 Surgical reconstruction of a femoral artery aneurysm extending beyond the common femoral artery bifurcation can be performed with different configurations, depending on local anatomy. The interposition graft can be placed between the common femoral and either the superficial femoral artery (A) or the profunda femoris artery (B) with reimplantation of the other branch into the side of the graft. C, If the origin of the artery to be implanted is diseased or not long enough, a short interposition graft can be used. (From O’Hara P: Treatment of femoral and popliteal artery aneurysms. In Zelenock GB, et al, editors: Mastery of vascular and endovascular surgery, Philadelphia, 2006, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.)

Endovascular Treatment

Endovascular treatment of CFA aneurysms has largely been limited to emergency situations or performed as part of a hybrid approach with an open surgical procedure. Bakoyiannis et al21 described such a procedure using a stent-graft to exclude a distal external iliac artery aneurysm and a traditional Dacron graft for the femoral portion of a large aneurysm extending from the distal external iliac artery into the common femoral artery. Percutaneous endovascular treatment of a ruptured femoral artery aneurysm has also been described.20 Contralateral femoral access is often required in these cases for delivery of the stent-graft. However, caution should be used in the consideration of placement of a stent graft in the CFA, particularly when it crosses the inguinal ligament, because of possible stent fracture or dislodgement in this location.

Endovascular techniques can be used as adjuncts to open procedures. For example, proximal control can be obtained via a balloon placed under fluoroscopic guidance through the opened aneurysm sac in standard surgery22 or percutaneously via the contralateral CFA when necessary.

Pseudoaneurysms

Pseudoaneurysms in the CFA occur most commonly from iatrogenic causes such as instrumentation for cardiac or peripheral catheterization and after open reconstructions.13,23 Iatrogenic false aneurysms can be treated with open surgery or ultrasound-guided therapy, or with observation alone if they are small in diameter. Pseudoaneurysms may also occur as a result of infection that causes focal erosion of the arterial wall, usually from external sources such as contaminated needles used during intravascular substance abuse. Management of infected pseudoaneurysms is difficult and requires ligation either alone or with extra-anatomic bypass.24 Infected aneurysms are discussed in detail in Chapter 142. Management of anastomotic pseudoaneurysms is discussed in Chapter 44.

Clinical Findings and Natural History

The most common clinical manifestation of a femoral pseudoaneurysm is a painful pulsating mass in the groin, usually with an associated hematoma. Femoral bruits are heard frequently, and if an arteriovenous fistula is present, the bruit has a characteristic continuous to-and-fro quality. Patients may also complain of femoral neuropathic pain, paresis of hip flexion, or edema from compression of adjacent structures. Progressive enlargement can result in overlying skin ischemia and necrosis. In our experience, distal embolization or limb ischemia is rare. Rupture can lead to cardiovascular collapse and death from hemorrhagic shock and is a surgical emergency.25 Significant bleeding can occur without overt clinical findings if the initial puncture is in the external iliac artery or through the inguinal ligament and results in occult bleeding into the retroperitoneal space.

Aneurysm size and the presence of anticoagulation determine which pseudoaneurysms require treatment. Most aneurysms less than 2 or 3 cm in diameter undergo spontaneous thrombosis and may be safely observed with periodic DUS examinations. Continued anticoagulation therapy greatly decreases the likelihood of spontaneous closure of such a pseudoaneurysm.26,27 In one prospective series, 18 pseudoaneurysms were identified after 1838 femoral catheterizations over an 8-month period (0.98% incidence). Aneurysms that were less than 1.8 cm in diameter and causing no symptoms were observed. Surgical repair was carried out if the aneurysms enlarged by 100% or did not close within 2 months. Of the 16 that were managed expectantly, half underwent spontaneous thrombosis and the other half required repair. Although the difference did not reach statistical significance, the likelihood of spontaneous closure was lower for aneurysms more than 1.8 cm in diameter, and no aneurysm closed spontaneously in the presence of continued anticoagulation regardless of size.28

Diagnosis

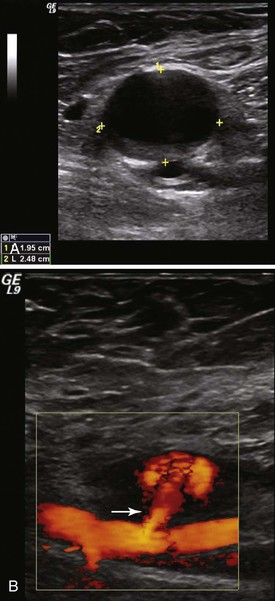

Duplex ultrasound is the preferred imaging method. The sensitivity and specificity of DUS for femoral false aneurysms are 94% and 97%, respectively.29 Duplex ultrasound also provides important information on diameter, morphology, and anatomy of the neck and location of the femoral artery defect. On B-mode imaging, an aneurysm appears as a characteristic echolucent mass adjacent to the femoral artery and a channel, usually narrow, with arterial flow into the mass (Fig. 139-3).

Figure 139-3 A, Duplex ultrasound of a femoral false aneurysm in B mode demonstrating a large echolucent mass anterior to the femoral artery. The cursor marks the dimensions of the aneurysm cavity. B, Color-flow imaging demonstrating blood entering the aneurysm sac via a relatively long channel or “neck” (arrow) arising from the femoral artery.

Treatment

Ultrasound-Guided Compression.

Compression of false aneurysms to induce thrombosis was proposed as a less invasive alternative to surgery in 1991.30 Duplex ultrasound is used to locate the aneurysm, and suitable pressure is applied with the transducer to stop flow within the aneurysm cavity while maintaining flow in the adjacent femoral artery. Excessive pressure can result in femoral artery thrombosis.31 Compression is maintained for 10 to 20 minutes, after which time flow is reassessed. If flow persists, the procedure is repeated one or more times until flow within the aneurysm cavity is noted to have stopped. The patient is kept on bed rest for 6 hours, being reevaluated with DUS at 24 and 48 hours after the procedure to rule out recurrence. If the procedure is performed in the outpatient setting, the patient may be discharged home after the initial 6 hours.

Success rates for ultrasound-guided compression (UGC) range from 66% to 86%, with required compression times averaging 30 to 44 minutes.30–32 Recurrence has been reported in 4% of cases.31 The presence of anticoagulation greatly reduces the likelihood of success to less than 40%.31–33 UGC is contraindicated in patients with ischemic skin changes or infection and when the puncture site originates above the inguinal ligament. Moreover, UGC is not usually possible in patients with severe pain and very large hematomas. Imaging and compression are technically more difficult in obese patients, thus decreasing the likelihood of success. Aneurysm rupture, femoral vein thrombosis, limb ischemia from femoral arterial thrombosis, and hypotension from vasovagal events are all potential complications that have occurred in 2% to 4% of cases.31,32,34

From a practical standpoint, UGC has the disadvantage of being time-consuming and placing demands on the vascular laboratory, time, equipment, and personnel. Operator and patient fatigue and management of the often significant pain that patients experience during compression are common problems.35 Use of mechanical compression devices can obviate some of these issues but requires a cooperative and immobile patient and repeated reevaluation during compression.36 Such devices offer little advantage and have not generally been widely accepted.

Ultrasound-Guided Thrombin Injection.

Angiographically directed thrombin injection via percutaneous access into the aneurysm cavity to induce immediate thrombosis was first described by Cope et al37 more than 20 years ago. Kang et al38 modified the technique by performing direct percutaneous aneurysm puncture under duplex ultrasound guidance. Thrombin directly converts fibrinogen to fibrin, thereby leading to immediate clot formation and “short-circuiting” the upstream mechanism of the coagulation cascade, where heparin and warfarin interact. Consequently, thrombin injection is effective even in patients receiving anticoagulation. Bovine and human thrombin are commercially available in powder form that is reconstituted in normal saline immediately before use.

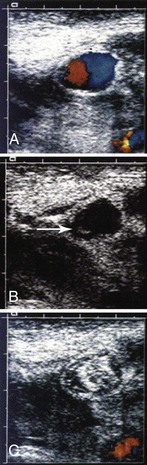

Ultrasound-guided thrombin injection (UGTI) is quick, simple, and relatively painless. Duplex ultrasound is used to identify the aneurysm cavity. After infiltration with local anesthetic, the cavity is punctured with either a 22-gauge catheter or a 25-gauge hypodermic needle. Spinal needles can be used for deeper aneurysms. Identification of the needle or catheter within the aneurysm sac is a critical step (Fig. 139-4) and can be facilitated with the use of a commercially available echodense needle.39–41 The needle is filled with thrombin, which when inserted causes a small clot to form at the needle tip that is readily visualized on ultrasound.38 Once proper positioning of the needle is confirmed, thrombin (1000 IU/mL) is injected slowly through a 3-mL syringe for a period of about 10 to 15 seconds, until flow within the cavity ceases. In our experience and that of others, approximately 1000 units of thrombin is required to induce thrombosis. It is important to inject slowly and to stop immediately once thrombosis has occurred to minimize the chance of thrombin’s entering the circulation. A second injection is sometimes required.38 Patients are given bed rest for 1 hour. Duplex ultrasound is repeated 24 hours later to confirm permanent thrombosis of the aneurysm. UGTI has a success rate of 96% to 100%.39,42–44 Second injections of thrombin are necessary in up to 7% of cases to achieve complete thrombosis.44

Figure 139-4 Duplex ultrasound of a femoral pseudoaneurysm. A, Color-flow image demonstrating typical swirling flow in the pseudoaneurysm cavity. B, Image taken 18 seconds later with color flow turned off shows the tip of a 22-gauge needle in the left lower portion of the pseudoaneurysm (arrow). After placement of the needle, color flow is turned back on and thrombin is injected. C, Color-flow image demonstrating that the pseudoaneurysm cavity is completely filled with echogenic thrombus. (From Kang SS, et al: Percutaneous ultrasound guided thrombin injection: a new method for treating postcatheterization femoral pseudoaneurysms. J Vasc Surg 27:1032-1038, 1998.)

Most writers prefer to use UGTI to treat pseudoaneurysms and to use UGC only in patients in whom thrombin products are contraindicated. Contraindications to bovine thrombin include known allergy, infection, and pregnancy. A relative contraindication to UGTI is a short, wide channel or “neck” of flow into the pseudoaneurysm. In these cases there can be a higher incidence of embolization of thrombus into the CFA with thrombin injection. An update of a Cochrane review compared multiple no-surgical treatments, including ultrasound-guided compression, blind compression, and ultrasound-guided thrombin injections. Compression was effective in achieving pseudoaneurysm thrombosis. Ultrasound-guided application did not confer additional benefit. Percutaneous thrombin injection was more effective than a single session of ultrasound-guided compression within individual randomized controlled trials.45

Open Surgical Repair.

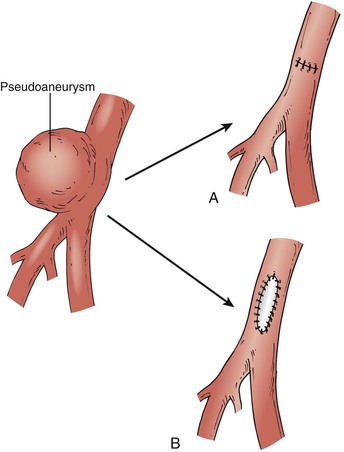

Open surgical repair is usually reserved for ruptured pseudoaneurysms, failures of or contraindications to UGC or UGTI, overlying skin ischemia, or pseudoaneurysms associated with an arteriovenous fistula. Direct repair with polypropylene sutures or patch angioplasty is an effective method of repair (Fig. 139-5). However, complications are not infrequent, with wound complications in up to 4% to 8% of cases and an associated mortality rate of 2.9% related to the underlying cardiac disease for which the catheterizations are often performed.45,46 In high-risk cases, open repair can be performed with local anesthesia and the use of balloon occlusion for proximal control of the external iliac artery. If there is extensive damage to the femoral arterial wall, patch angioplasty with autologous or synthetic tissue may be required. Autologous tissue is preferred, because pseudoaneurysms may be associated with latent infections.

Figure 139-5 Surgical repair of a femoral artery false aneurysm. After proximal and distal control is obtained, the sac is opened and the arterial defect exposed. Repair can be accomplished in most cases by direct suture repair (A), although patch angioplasty may occasionally be required (B). (From O’Hara P: Treatment of femoral and popliteal artery aneurysms. In Zelenock GB, et al, editors: Mastery of vascular and endovascular surgery, Philadelphia, 2006, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.)

Superficial Femoral Artery Aneurysms

Isolated aneurysms of the SFA are rare and considerably less common than those of the common femoral artery. They more commonly manifest as proximal extensions of popliteal artery aneurysms. An extensive review of all language literature by Leon et al47 identified 61 reported cases of isolated SFA aneurysms. They occurred most commonly in elderly men (87%), with an average age of 75.7 years. Most were located in the middle third of the artery and were large at presentation, with a mean diameter of 8.4 cm at diagnosis. Such a large size is likely related to the deep anatomic location of the distal SFA, which precludes early detection. The most common mode of manifestation was a pulsatile tender thigh mass (59%) associated with localized pain. Rupture was more common manifestation (42%) than distal ischemia (13%), and repair most commonly consisted of interposition graft or exclusion with bypass. Limb salvage rate is reported at greater than 90%. Endovascular repair was reported in three cases in this review.47

Because of the rare nature of this entity, the natural history is not well known, and no specific aneurysm diameter has been identified at which the incidence of complications increases. SFA aneurysms of 2.5 cm or more in diameter, particularly those that are known to have grown over time, are usually repaired. Duplex ultrasound scan is an accurate imaging modality for following smaller asymptomatic aneurysms.

Prior to surgical treatment, arteriography is performed to evaluate the inflow and outflow vessels. Either saphenous vein or prosthetic graft can be used. Prosthetic grafts work well in the groin or thigh and can usually be matched to the diameter of the artery. Vein grafts are preferred for any reconstruction crossing the knee joint, which may be necessary with distal occlusive disease or if the aneurysm is being treated in conjunction with a PAA. Exposure is obtained in either the groin or midthigh or at both sites, depending on the extent of the aneurysm. The surgical approach is nearly identical to that for popliteal aneurysm repair. Focal aneurysms are treated by opening of the sac, evacuation of thrombus, and creation of an end-to-end interposition graft. For more extensive aneurysms, proximal and distal ligation can be performed, followed by placement of a bypass graft. Although long-term follow-up is not available, Rigdon et al48 reported a limb salvage rate of 94% with no deaths, whereas Jarrett et al49 reported successful bypass in 11 cases with no mortality. Two patients underwent primary amputation for unsalvageable ischemia at initial evaluation.

Although endovascular repair has been reported in only a few instances of isolated SFA aneurysms, it is likely that percutaneous repair will become more prevalent as the profile of devices is reduced and they are easier to deploy. However, long-term data on the effectiveness of this treatment method are not available at this time.

Profunda Femoral Artery Aneurysms

Degenerative aneurysms of the PFA are extremely rare, representing less than 3% of all femoral artery aneurysms (Fig. 139-6). Most cases are unilateral, although bilateral aneurysms have also been reported.50 Synchronous aneurysms are common and occur in up to 70% of cases, popliteal aneurysms being the most common.51,52 They can manifest as either rupture or limb-threatening ischemia from distal embolization of thrombus, particularly if there is concomitant SFA occlusive disease. Like SFA aneurysms, PFA aneurysms are often of large size at presentation because of their deep anatomic location.53 Repair is always recommended because of the high rate of complications and unknown natural history of asymptomatic PFA aneurysms.

Figure 139-6 Arteriogram of a large symptomatic aneurysm of the profunda femoris artery (arrows). The aneurysm originates at the origin of the profunda femoris artery, and there is ectasia in the common femoral and superficial femoral arteries.

Surgical repair is carried out through a vertical groin incision. In most cases, aneurysmectomy within an interposition graft of either saphenous vein or prosthetic material is preferred. In the construction of interposition grafts, large branches of the profunda femoral artery should be preserved whenever possible. Dissection is usually started at the CFA bifurcation and extends inferiorly and slightly laterally over the course of the deep femoral artery. The SFA is retracted medially, and as the dissection extends more distally, the sartorius and rectus femoris muscles are reflected laterally. Larger crossing branches of the deep femoral vein are encountered and must be carefully divided and suture-ligated. Branches of the femoral nerve are also encountered and must be preserved and protected from injury by self-retaining retractors or cautery. Gentle dissection is necessary to avoid troublesome venous injury. Proximal control is usually obtained at the level of the CFA, although in instances of rupture with massive hematoma in the groin, control of the distal external iliac artery may be necessary. Distal arterial control can be accomplished with silicon rubber vessel loops or balloon catheter occlusion.

Although graft replacement is generally preferred, simple ligation may be a reasonable treatment for aneurysms confined to the distal branches of the deep femoral artery.54 Proximal PFA ligation may be also reasonable in patients with rupture, especially when the SFA is patent; however, such ligation may put the patient at risk for future limb ischemia and amputation.52 In highly selected cases of aneurysms involving distal branches of the PFA, embolization may be a reasonable nonsurgical alternative.55,56

Endovascular management of PFA aneurysms has been reported. Stent-grafts have been used to treat three cases of PFA pseudoaneurysms after instrumentation or penetrating trauma, with good short-term results.57 This approach may be effective in stable patients without major compressive symptoms. Coil embolization has also been shown to be successful treatment, particularly if the aneurysm involves distal branches of the main PFA.56 Embolization of the main PFA has been reported via a contralateral approach and may be a useful alternative if the SFA is patent.58

Persistent Sciatic Artery Aneurysm

Persistent sciatic artery (PSA) is a rare vascular anomaly present in 0.01% to 0.05% of the population. It is prone to aneurysmal degeneration, potentially leading to distal ischemia, sciatic neuropathy, and rupture. When present, most PSAs involve the dominant limb arteries of the lower extremity, with aneurysm formation occurring in up to 40% of cases. The femoral artery is often hypoplastic. The patient with PSA aneurysm may present with an enlarged buttock mass, with local compressive symptoms and distal ischemia. An interposition graft is the preferred method of repair.59 Because of potential damage to the adjacent sciatic nerve, exposure and surgical dissection of the aneurysm are not recommended.

Endovascular stent placement has been reported as an effective method of repair for PSA aneurysm, provided that there are no significant associated compressive symptoms.60 Embolization of a ruptured PSA aneurysm with Amplatzer plugs (St. Jude Medical, Inc., St. Paul, Minnesota) in a hemodynamically unstable patient has also been reported. This maneuver successfully controlled the hemorrhage but was complicated by footdrop, likely secondary to sciatic nerve ischemia and a buttock abscess.61

Popliteal Artery Aneurysms

The popliteal artery, a continuation of the superficial femoral artery in the thigh, extends from the adductor canal to the origin of the anterior tibial artery below the knee. The definition of what constitutes a popliteal artery aneurysm varies in the contemporary literature. The normal diameter of the popliteal artery varies with the size and gender of the patient, ranging from approximately 0.5 to 1.1 cm.11,62 Anatomic studies have now shown that the popliteal artery itself differs in diameter from proximal to distal, with the proximal portion more closely approximating the diameter of the SFA and the distal popliteal artery tending to be smaller.63 Most PAAs appear to occur in the proximal part or midportion of the artery. According to 1991 suggested standards, an aneurysm may be considered to be present if the total enlargement is 1.5 times the diameter of a normal adjacent segment of artery.11 Other writers consider a diameter of 1.5 cm or greater in the “average” patient to be an aneurysm, although in clinical practice most surgeons use 2 cm as the threshold diameter.

Epidemiology

PAAs are rather rare in the general population, although they are the most common peripheral artery aneurysms, accounting for at least 70% of them.64 PAAs are found almost exclusively in men. One study of hospitalized patients identified the incidence of femoral or popliteal artery aneurysms to be 7.4 per 100,000 men and only 1.0 per 100,000 women.64 Another study that screened more than 1000 men between the ages of 65 and 80 years in the United Kingdom revealed a prevalence of only about 1%.65 About 50% of patients have bilateral PAAs, and 30% to 50% of patients may have an associated abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA).7,66 On the contrary, less than 15% of all patients with AAAs have coexisting PAAs.6 In patients treated for isolated popliteal aneurysms, the likelihood of development of another aneurysm at a remote site over a 10-year period is estimated to be as high as 50%, thus mandating careful scrutiny of all patients at initial encounter and of lifelong surveillance after treatment.67

Pathogenesis

With the exclusion of trauma and rare congenital disorders, the majority of PAAs are considered to be true aneurysms, involving all layers of the arterial wall. Many writers in the past regarded PAAs as atherosclerotic, but most PAAs are degenerative. Jacob et al68 identified disruption and fragmentation of the elastic lamellae in the walls of PAA specimens in comparison with normal popliteal arteries. In addition, they identified decreased numbers of vascular smooth muscle cells in the walls and an increased expression of molecules linked to apoptosis. A significantly greater number of CD68+ macrophages and CD3+ T cells in the media of the PAA wall specimens were detected than in normal arteries. The researchers attribute the aneurysm formation to a loss of the mechanical integrity of the popliteal artery wall and the altered balance between the production and degradation of the vascular wall constituents.68

The anatomic location of the popliteal artery at a high flexion point and the encountered repetitive stresses of the artery in this location may be additional causative factors for PAAs.

Natural History

The mean growth rate for PAAs is 1.5 mm/year for PAAs smaller than 20 mm, 3 mm/year for PAAs 20 to 30 mm, and 3.7 mm/yr for those larger than 30 mm.69 Hypertension is the most common risk factor associated with increased PAA growth. In contrast to AAAs, PAAs rarely rupture, with a reported incidence of only 2.5%. In patients in whom rupture occurs, there is a very high rate of limb loss.70 When PAAs are symptomatic, they more typically manifest as acute or chronic ischemia due to distal embolization or thrombosis. Although it may be difficult to determine the actual percentage of patients with PAAs who become symptomatic over time, several series of observed patients report a high incidence of thromboembolic complications. Szilagyi et al71 reported that over a 5-year period, only 32% of observed (nonoperated) patients with PAA remained without lower extremity complications. Dawson et al67 reviewed 71 PAAs, 25 of which were initially treated nonsurgically. Complications developed in 12 of the 21 asymptomatic popliteal aneurysms (57%) and in 2 of the 4 symptomatic aneurysms (50%). The probability of development of complications increased with time to 74% within 5 years. Lowell et al72 identified the presence of aneurysmal thrombus and poor distal runoff as risk factors for ischemic complications among asymptomatic PAAs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree