It has not been adequately addressed yet how long the excess cardiovascular event risk persists after acute myocardial infarction (AMI) compared with stable coronary artery disease. Of 10,470 consecutive patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention either with sirolimus-eluting stent (SES) only or with bare-metal stent (BMS) only in the Coronary Revascularization Demonstrating Outcome Study-Kyoto Registry Cohort-2, 3,710 (SES: n = 820 and BMS: n = 2,890) and 6,760 patients (SES: n = 4,258 and BMS: n = 2,502) presented with AMI (AMI group) and without AMI (non-AMI group), respectively. During the median 5-year follow-up, the excess adjusted risk of the AMI group relative to the non-AMI group for the primary outcome measure (cardiac death or myocardial infarction) was significant (hazard ratio [HR] 1.53, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.30 to 1.80, p <0.001). However, the excess event risk was limited to the early period within 3 months. Late adjusted risk beyond 3 months was similar between the AMI and non-AMI groups (HR 1.16, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.41, p = 0.15). The higher risk of the AMI group relative to the non-AMI group for stent thrombosis (ST) was significant within 3 months (HR 3.38, 95% CI 2.04 to 5.60, p <0.001), whereas the risk for ST was not different between the 2 groups beyond 3 months (HR 1.11, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.90, p = 0.70). There were no interactions between the types of stents implanted and the risk of the AMI group relative to the non-AMI groups for all the outcome measures including ST. In conclusion, patients with AMI compared with those without AMI were associated with similar late cardiovascular event risk beyond 3 months after percutaneous coronary intervention despite their higher early risk within 3 months.

Patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) compared with those without AMI are associated with higher long-term risk for cardiovascular (CV) events after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Based on their higher event risk, more intensive long-term secondary preventive medications such as longer duration of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), aggressive lipid-lowering therapy, and β-blocker therapy are recommended for patients with AMI in the current guidelines. Furthermore, novel therapeutic agents aiming at further reducing long-term CV event risk have often been investigated in patients after AMI. In the early phase after PCI, the CV event risk in patients with AMI is clearly higher than that those without AMI. However, it has not been adequately addressed yet how long the excess CV event risk of patients with AMI relative to those without AMI persists after PCI. We sought to investigate the late clinical outcome after coronary stent implantation in patients with AMI presentation in comparison with those without AMI presentation in a large Japanese observational database of patients who underwent first coronary revascularization.

Methods

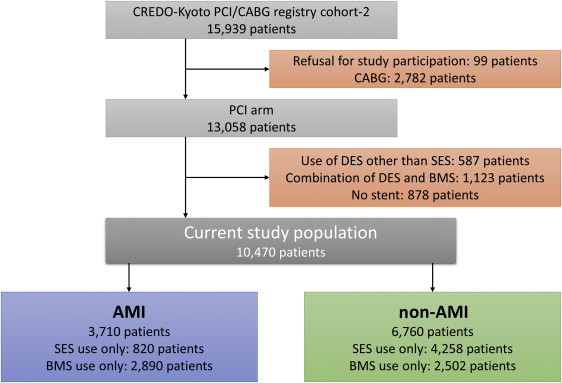

The Coronary Revascularization Demonstrating Outcome (CREDO) study in Kyoto Registry Cohort-2 is a multicenter registry enrolling consecutive patients who underwent first coronary revascularization procedures in 26 centers in Japan from January 2005 to December 2007. The design and outcomes of the entire PCI cohort of the CREDO-Kyoto PCI/CABG RegistryCohort-2 has been described previously. The relevant review boards in all participating centers approved the research protocol. Of 13,058 patients in the PCI arm of the registry, 10,470 patients underwent PCI either with sirolimus-eluting stent (SES) only (n = 5,078) or with bare-metal stent (BMS) only (n = 5,392). Of these, 3,710 patients presented with AMI at the time of PCI (AMI group—SES [n = 820], BMS [n = 2,890]; ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction [STEMI] [n = 3,177], non-STEMI [n = 533] whereas 6,760 patients presented without AMI (non-AMI group—SES [n = 4,258], BMS [n = 2,502]; Figure 1 ).

The primary outcome measure in the present analysis was a composite of cardiac death and myocardial infarction (MI). Other clinical outcome measures included all-cause death, cardiac death, MI, stent thrombosis (ST), and target-lesion revascularization (TLR). We mainly focused on the late adverse events beyond 3 months after coronary stent implantation in an attempt to investigate how long the excess CV event risk persists in patients with AMI compared with those without AMI. ST was defined as definite ST according to the Academic Research Consortium definition. TLR was defined as either PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting because of restenosis or thrombosis of the target lesion that included the proximal and distal edge segments and the ostium of the side branches. MI was defined according to the definition in the Arterial Revascularization Therapy Study. Within 1 week of the index procedure, only Q-wave MI was adjudicated as MI. Follow-up data on clinical events together with status of antiplatelet therapy were collected from the hospital charts in the participating centers, letters to patients, and telephone call to referring physicians by the experienced clinical research co-ordinators in the independent clinical research organization (Research Institute for Production Development, Kyoto, Japan). Clinical events, such as ST, MI, and stroke, were adjudicated based on the original source documents by a clinical event committee, as previously described.

The recommended antiplatelet therapy regimen was aspirin (≥81 mg daily) indefinitely and thienopyridine (200 mg ticlopidine or 75 mg clopidogrel daily) for at least 3 months after drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation. The duration of DAPT was left to the discretion of each attending physician. Status of antiplatelet therapy during follow-up was also evaluated. Dates of discontinuation of aspirin and thienopyridine were reported separately during follow-up. If either aspirin or thienopyridine was restarted after discontinuation, the dates of restart were also recorded. Persistent discontinuation of thienopyridine was defined as withdrawal lasting at least 2 months.

Categorical variables were compared with the chi-square test. Continuous variables were expressed as mean value ± SD or median and interquartile range. Continuous variables were compared using the Student’s t test. We compared the clinical outcomes between the 2 groups of patients with or without AMI presentation. Cumulative incidences were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences were assessed with the log-rank test. To evaluate the late adverse events beyond 3 months, we used landmark analysis at 3 months. The specific landmark point of 3 months was selected by the visual evaluation of the Kaplan-Meier curves for the AMI and non-AMI groups through the entire follow-up period. Those patients with the individual end point events before the landmark point were excluded in the landmark analysis. We used Cox proportional hazard models to estimate the risk of AMI relative to non-AMI for clinical end points adjusting for the differences in patient characteristics, procedural factors, and medications. Consistent with our previous report, we chose 39 clinically relevant factors as risk-adjusting variables. Because the number of definite ST events was limited, 18 selected variables were used in the adjustment for definite ST ( Table 1 ). The continuous variables were dichotomized by clinically meaningful reference values or median values. The stent type and the risk-adjusting variables were simultaneously included in the Cox proportional hazard model for the adjusted analyses. Center was included in the model as the stratification variable. The effect of AMI relative to non-AMI was expressed as hazard ratios (HR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). To assess whether the effects of AMI relative to non-AMI were different between the DES and BMS strata, we added interaction variable between the clinical presentation (AMI or non-AMI) at the index procedure and the stent types (SES or BMS) in the model.

| Variable | AMI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N=3710) | No (N=6760) | ||

| Age (years) | 67.5±12.4 | 68.5±10.3 | <0.001 |

| ≥75 years ∗ † | 1162 (31%) | 2102 (31%) | 0.81 |

| Male ∗ † | 2702 (73%) | 4844 (72%) | 0.20 |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) | 23.6±3.5 | 23.8±3.4 | 0.008 |

| Body mass index <25.0 kg/m 2 ∗ | 2633 (70%) | 4520 (67%) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension ∗ † | 2889 (78%) | 5687 (84%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1207 (33%) | 2649 (39%) | <0.001 |

| Insulin therapy ∗ † | 150 (4.0%) | 625 (9.3%) | <0.001 |

| Current smoker ∗ † | 1544 (42%) | 1816 (27%) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure ∗ † | 1134 (31%) | 923 (14%) | <0.001 |

| Shock at presentation ∗ | 612 (17%) | 1 (0.01%) | <0.001 |

| Multivessel coronary disease ∗ † | 1698 (46%) | 3688 (55%) | <0.001 |

| Multivessel PCI | 660 (39%) | 1822 (49%) | <0.001 |

| Staged PCI | 542 (32%) | 1148 (31%) | 0.56 |

| Mitral regurgitation grade 3 or 4 ∗ | 95 (2.6%) | 299 (4.4%) | <0.001 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 53.4±12.7 | 61.6±12.4 | <0.001 |

| Ejection fraction ≦ 40% | 464 (16%) | 411 (7.1%) | <0.001 |

| Previous myocardial infarction ∗ † | 100 (2.7%) | 967 (14%) | <0.001 |

| Previous stroke ∗ | 331 (8.9%) | 754 (11%) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease ∗ | 109 (2.9%) | 688 (10%) | 0.04 |

| eGER <30 ml/min/1.73 m 2 , not on dialysis ∗ | 175 (4.7%) | 257 (3.8%) | 0.02 |

| Dialysis ∗ | 41 (1.1%) | 303 (4.5%) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation ∗ † | 328 (8.8%) | 565 (8.4%) | 0.40 |

| Anemia (hemoglobin <11 g/dL) ∗ | 381 (10%) | 815 (12%) | 0.006 |

| Platelet <100 ∗ 10 9 /L ∗ | 65 (1.8%) | 86 (1.3%) | 0.049 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease ∗ | 117 (3.2%) | 266 (3.9%) | 0.04 |

| Liver cirrhosis ∗ | 89 (2.4%) | 181 (2.7%) | 0.39 |

| Malignancy ∗ | 284 (7.7%) | 696 (10%) | <0.001 |

| Procedural characteristics | |||

| DES use ∗ † | 820 (22%) | 4258 (63%) | <0.001 |

| Number of target lesions | 1.29±0.60 | 1.43±0.72 | <0.001 |

| Target of proximal LAD ∗ † | 1971 (53%) | 3992 (59%) | <0.001 |

| Target of unprotected LMCA ∗ † | 119 (3.2%) | 207 (3.1%) | 0.68 |

| Target of CTO ∗ † | 99 (2.7%) | 913 (14%) | <0.001 |

| Target of bifurcation ∗ † | 911 (25%) | 2287 (34%) | <0.001 |

| Side-branch stenting ∗ † | 92 (2.5%) | 281 (4.2%) | <0.001 |

| Total number of stents | 1.49±0.88 | 1.77±1.13 | <0.001 |

| Total stent length | 30.9±20.2 | 38.1±28.1 | <0.001 |

| Total stent length >28 mm ∗ † | 1321 (36%) | 3157 (47%) | <0.001 |

| Minimum stent size | 3.06±0.46 | 2.90±0.44 | <0.001 |

| Minimum stent size <3.0 mm ∗ † | 1074 (29%) | 3040 (45%) | <0.001 |

| Medication at hospital discharge | |||

| Antiplatelet therapy | |||

| Thienopyridine | 3647 (98%) | 6703 (99%) | <0.001 |

| Ticlopidine | 3329 (90%) | 6061 (90%) | 0.93 |

| Clopidogrel | 374 (10%) | 677 (10%) | 0.93 |

| Aspirin | 3666 (99%) | 6662 (99%) | 0.26 |

| Cilostazole ∗ | 1276 (34%) | 719 (11%) | <0.001 |

| Other medications | |||

| Statins ∗ | 1945 (52%) | 3386 (50%) | 0.02 |

| β-blockers ∗ | 1474 (40%) | 1661 (25%) | <0.001 |

| ACE-I/ARB ∗ | 2655 (72%) | 3401 (50%) | <0.001 |

| Nitrates ∗ | 1041 (28%) | 2630 (39%) | <0.001 |

| Calcium channel blockers ∗ | 732 (20%) | 3495 (52%) | <0.001 |

| Nicorandil ∗ | 1008 (27%) | 1429 (21%) | <0.001 |

| Warfarin ∗ | 344 (9.3%) | 473 (7.0%) | <0.001 |

| Proton pump inhibitors ∗ | 1284 (35%) | 1397 (21%) | <0.001 |

| H2-blockers ∗ | 1219 (33%) | 1494 (22%) | <0.001 |

∗ Variables selected in multivariable analysis.

† Variables selected in multivariable analysis for definite stent thrombosis.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York). All the statistical analyses were 2 tailed. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients in the AMI group and those in the non-AMI group were significantly different in baseline clinical and procedural characteristics ( Table 1 ). Patients in the AMI group were more often smokers and more frequently presented with heart failure, reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, and shock, whereas those in the non-AMI group were older and had greater prevalence of CV risk factors, such as hypertension and diabetes, and history of CV events, such as MI and stroke. In terms of lesion and procedural characteristics, patients in the AMI group had significantly less complex lesion characteristics, and smaller number of target lesions compared with those in the non-AMI group. Patients in the AMI group were more often treated with BMS, whereas those in the non-AMI group were more often treated with DES. In patients with multivessel coronary artery disease (CAD), the prevalence of multivessel PCI and scheduled staged PCI was relatively high in both AMI and non-AMI groups. Regarding baseline medications, β blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, proton pump inhibitors, and H2 blockers were more often used in the AMI group, whereas calcium channel blockers were more often used in the non-AMI group. The differences in baseline characteristics between AMI and non-AMI groups were mostly consistent in both DES and BMS strata ( Supplementary Table 1 ).

Median follow-up duration of the survivors was 5.4 years (range 0 to 7.6 and interquartile range 4.7 to 6.1). Thienopyridine was continued significantly longer after DES implantation than after BMS implantation (persistent discontinuation of thienopyridine at 1 year 33% vs 73%, p <0.001). Because of the dominance of patients with BMS in the AMI group, patients in the AMI group compared with those in the non-AMI group more often discontinued thienopyridine therapy early (persistent discontinuation of thienopyridine at 6 months: 54% vs 36%, p <0.001). In the DES stratum, the AMI group more often discontinued thienopyridine therapy than the non-AMI group, whereas in the BMS stratum, the AMI group less often discontinued thienopyridine therapy than the non-AMI group ( Figure 2 ).