Long-term outcomes of unselected patients with angina pectoris and bundle branch block (BBB) on initial electrocardiogram are not well established. The Olmsted County Chest Pain Study is a community-based cohort of 2,271 consecutive patients presenting to 3 Olmsted County emergency departments with angina from 1985 through 1992. Patients were followed for major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) including death, myocardial infarction, stroke, and revascularization at 30 days and over a median follow-up period of 7.3 years and for mortality only through a median of 16.6 years. Cox models were used to estimate associations between BBB and cardiovascular outcomes. Mean age of the cohort on presentation was 63 years, and 58% were men. MACEs at 30 days occurred in 11% with right BBB (RBBB), 8.8% with left BBB (LBBB), and 6.4% in patients without BBB (p = 0.17). Over a median follow-up of 7.3 years, patients with BBB were at higher risk for MACEs (RBBB, hazard ratio [HR] 1.85, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.44 to 2.38, p <0.001; LBBB, HR 2.04, 95% CI 1.62 to 2.56, p <0.001) compared to those without BBB. Over a median of 16.6 years, the 2 BBB groups had lower survival rates than patients without BBB (RBBB, HR 2.19, 95% CI 1.73 to 2.78, p <0.001; LBBB, HR 3.32, 95% CI 2.67 to 4.13, p ≤0.001), but after adjustment for multiple risk factors an increased risk of mortality for LBBB remained significant. In conclusion, appearance of LBBB or RBBB in patients presenting with angina predicts adverse long-term cardiovascular outcomes compared to patients without BBB.

In the setting of an acute coronary syndrome, the prognosis is worse in patients in whom bundle branch block (BBB) is new and or persistent. However, owing to the uncertainty in reliably differentiating new from old BBB, patients with BBB, especially right BBB (RBBB), presenting with acute coronary syndrome are managed no differently than those without BBB, although more favorable outcomes have been reported with aggressive management. The long-term clinical implications of BBB in a community-based cohort with angina are unknown. This analysis from the Olmsted County Chest Pain Study was conducted to elucidate the short- and long-term prognostic significance of BBB in patients presenting to the emergency department with angina.

Methods

Complete medical records of eligible patients were obtained through resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP), which allows comprehensive capture of details of health care experiences including outpatient care of all residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota (OC). The OC Health Care Utilization and Expenditures Database, which is linked to the REP, contains detailed line-item information on health services use and expenditures incurred by every member of the population for as long as they reside in the county. Unlike other geographically defined United States communities, a complete health services use history is available for all OC residents including the affiliation of their health care provider, site of care (inpatient, outpatient, or nursing home), and participating health insurance plan.

Using written screening logs, we retrospectively identified all residents of OC presenting to 1 of the county’s 3 emergency departments with angina from January 1, 1985 through December 31, 1992. Complete medical records of the screened population were reviewed by an experienced nurse abstractor who identified all county residents presenting with a first episode of angina defined according to the Diamond classification based on new or worsening pattern of ischemic anterior or left lateral chest pain occurring at rest or with minimal exertion and alleviated by sublingual nitroglycerin and/or rest. Patients were excluded if they had ST-segment elevation ≥1 mm in ≥2 contiguous leads suggestive of acute myocardial infarction on initial electrocardiogram or an alternate cause of chest pain including musculoskeletal pain, pneumonia, pleurisy, pericarditis, gastritis, pulmonary thromboembolism, or dissecting aortic aneurysm. Patients who died in the emergency department (n = 11) were also excluded. From the record review, the history of the qualifying episode was abstracted including medical history and findings on physical examination.

The initial electrocardiogram was interpreted by a staff cardiologist from the Mayo Clinic and verified by 1 of the study physicians. RBBB and left BBB (LBBB) were defined using the Minnesota Code. A diagnosis of RBBB required a QRS duration >120 ms in the presence of normal sinus or other supraventricular rhythm, R wave or RSR′ complex in lead V 1 , and an R complex with a prolonged shallow S wave in lead V 5 , V 6 , aVL, or I. LBBB was coded if all following criteria were met: QRS complex duration >120 ms in the presence of normal sinus or other supraventricular rhythm, QS or RS complex in lead V 1 , broad or notched R waves in leads V 5 and V 6 , or an RS pattern, and absence of Q wave in lead V 5 , V 6 , or I.

Long-term outcome data were collected in 2 phases. In the first phase, data were collected on major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) consisting of death, myocardial infarction, stroke and need for urgent revascularization, and incident heart failure and pacemaker implantation. Study subjects for whom there was no subsequently documented medical care visits in OC were contacted to determine vital status. A letter to a patient’s last recorded address initiated this contact. If there was no response, verification of status was confirmed through telephone contact with the patient directly or with a family member, physician, medical institution, or nursing home. Ninety-three percent of patients were followed through 1995 or later.

In the second phase, the last known alive date or death date as of January 2007 was added. The last known alive date was obtained from patient records of the Mayo Clinic. Dates of death were obtained through State of Minnesota Electronic Death Certificates, State of Minnesota Death Tapes, OC Electronic Death Certificates, and Mayo Clinic records. Thirty-seven patients were excluded in this phase because they refused to allow access to their records for research (as required by the State of Minnesota).

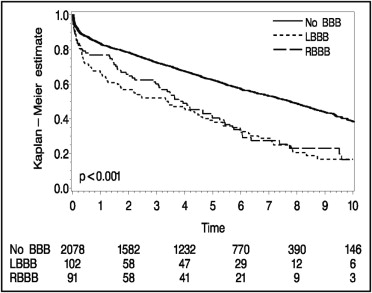

Patients were subclassified based on RBBB, LBBB, or no BBB (NBBB) and comparisons were made across these groups for MACEs and mortality. Thirty-day event rates were compared using Pearson chi-square test. Long-term survival rates were estimated by Kaplan–Meier methods and compared using log-rank statistic. Logistic regression models were used to estimate unadjusted odds ratios for primary MACEs within the first 30 days of arrival to the emergency department. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) for long-term survival and survival free of MACEs. The following covariates were selected for the model based on clinical significance: age, gender, history of smoking, diabetes, hypertension, systolic blood pressure, total serum cholesterol, family history of coronary disease, long-term aspirin use before emergency department presentation, previous myocardial infarction or history of coronary artery disease, previous revascularization, ST-segment depression ≥1 mm on initial electrocardiogram, extracardiac arterial disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and pulmonary edema.

Results

During the study period, 6,801 residents of OC presented to an emergency department with a first episode of acute chest pain. Of these 2,271 (33.4%) met the criteria for angina and were followed as study subjects for a median of 7.3 years for MACEs. Of ineligible patients cardiac disease accounted for 6.7% of presenting syndromes including ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in 5.5%, stable angina pectoris in 1.0%, and aortic dissection in 0.2%. Noncardiac causes of chest pain accounted for 36.2% of ineligible patients, in 23.9% the cause of symptoms was not determined, 17.6% were nonresidents, and 15.6% refused to participate. After extending follow-up for collection of data on vital status, 2,234 study subjects were followed for a median of 16.6 years.

Mean age ± SD of the cohort on presentation was 63 ± 40 years, 57.5% were men, and 14.8% had diabetes ( Table 1 ). Based on Minnesota criteria, 91 subjects (4%) had RBBB, 102 (4.5%) had LBBB, and 2,078 had NBBB on initial electrocardiogram. Subjects with RBBB were older, more likely to have a history of coronary artery disease (including previous myocardial infarction or angina), and a diagnosis of hypertension compared to patients with NBBB. Patients with either BBB were typically older with a history of myocardial infarction, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or hypertension but less likely to have smoked tobacco. Women in this cohort were more likely to have LBBB at presentation than men. Patients with either BBB were more often admitted to hospital on presentation with chest pain.

| Characteristics | Total | RBBB | LBBB | NBBB | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 2,271) | (n = 91) | (n = 102) | (n = 2,078) | ||

| Age (years), mean (range) | 63 (21–101) | 72 (31–92) | 72 (44–96) | 62 (21–101) | <0.001 |

| Men | 1,306 (57.5%) | 66 (72.5%) | 43 (42.2%) | 1,197 (57.6%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 336 (14.8%) | 14 (15.4%) | 18 (17.6%) | 304 (14.6%) | 0.69 |

| Smoked at presentation | 490 (21.6%) | 11 (12.1%) | 15 (14.7%) | 464 (22.3%) | 0.015 |

| Chronic obstructive lung disease | 319 (14.1%) | 20 (28%) | 29 (22%) | 270 (13%) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension (>140/90 mm Hg) | 1,039 (45.8%) | 56 (61.5%) | 56 (54.9%) | 927 (44.6%) | 0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 794 (35.0%) | 35 (38.5%) | 38 (37.3%) | 721 (34.7%) | 0.67 |

| Previous aspirin use | 395 (17.4%) | 19 (20.9%) | 22 (21.6%) | 354 (17.0%) | 0.33 |

| Any electrocardiographic abnormality | 1,257 (55.4%) | 91 (100.0%) | 102 (100.0%) | 1,064 (51.2%) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure at index date (mm Hg), mean (range) | 153 (60–300) | 155 (65–240) | 149 (60–225) | 153 (68–300) | 0.40 |

| Diastolic blood pressure at index date (mm Hg), mean (range) | 87 (34–170) | 85 (50–130) | 85 (40–145) | 88 (34–170) | 0.054 |

During the first 30 days after presentation, 153 patients (6.7%) had ≥1 primary MACE ( Table 2 ), 11% in those with RBBB, 8.8% in the LBBB group, and 6.4% in those with NBBB (p = 0.17). Patients with either BBB had no greater increase of cardiac enzyme levels at presentation than patients without BBB (RBBB 19.8%, LBBB 20.6%, NBBB 18.0%, p = 0.74). Patients with LBBB were more likely to develop clinical heart failure, however, during the first 30 days than those with RBBB or NBBB (p = 0.002; Table 2 ).

| Variable | Aggregate | RBBB | LBBB | NBBB | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 2,271) | (n = 91) | (n = 102) | (n = 2,078) | ||

| Death | 57 (2.5%) | 4 (4.4%) | 5 (4.9%) | 48 (2.3%) | 0.13 |

| Cardiovascular death | 50 (2.2%) | 4 (4.4%) | 4 (3.9%) | 42 (2.0%) | 0.15 |

| Myocardial infarction | 47 (2.1%) | 3 (3.3%) | 5 (4.9%) | 39 (1.9%) | 0.078 |

| Stroke | 14 (0.6%) | 2 (2.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 12 (0.6%) | 0.11 |

| Revascularization | 59 (2.6%) | 2 (2.2%) | 1 (1.0%) | 56 (2.7%) | 0.55 |

| Heart failure | 93 (4.1%) | 5 (5.5%) | 11 (10.8%) | 77 (3.7%) | 0.002 |

⁎ Excludes deaths in emergency department during initial evaluation.

During the first phase of long-term follow-up (median 7.3 years), MACEs were recognized in 1,136 patients, of whom 709 died. Unadjusted Kaplan–Meier survival curves showed that patients with RBBB or LBBB on presenting electrocardiogram were more likely to develop MACEs ( Figure 1 ) than those without BBB. The prognosis with RBBB was no better than with LBBB with respect to MACEs during this period ( Table 3 ), but after multivariate adjustment for clinical risk factors, only LBBB was significantly associated (p = 0.004) with MACEs during follow-up ( Table 4 ). Patients with RBBB were more likely than those with LBBB or NBBB to undergo pacemaker implantation over the 7-year follow-up period (p <0.001; Table 3 ). Patients with BBB were more likely to have developed heart failure over the 7 years (p <0.001; Table 3 ).

| Variable | Aggregate | RBBB | LBBB | NBBB | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 2,271) | (n = 91) | (n = 102) | (n = 2,078) | ||

| Total death | 588 (29.8%) | 39 (46.0%) | 64 (65.8%) | 485 (27.2%) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular death | 298 (15.9%) | 23 (30.2%) | 44 (50.1%) | 231 (13.6%) | <0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 294 (15.9%) | 21 (35.3%) | 24 (31.9%) | 249 (14.5%) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 162 (9.9%) | 7 (13.6%) | 7 (9.9%) | 148 (9.7%) | 0.413 |

| Revascularization | 394 (21.4%) | 17 (25.9%) | 14 (19.3%) | 363 (21.3%) | 0.837 |

| Pacemaker implantation | 74 (4.2%) | 12 (19.2%) | 5 (5.7%) | 57 (3.5%) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 441 (23.0%) | 30 (41.0%) | 48 (59.4%) | 363 (20.6%) | <0.001 |

| Any event (excluding heart failure and pacemaker implantation) | 1,006 (49.2%) | 62 (72.6%) | 71 (71.2%) | 873 (46.9%) | <0.001 |

⁎ Excludes deaths in emergency department during initial evaluation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree