Chapter 27 Liver Transplantation

History

The kidney was the first organ in which transplantation was attempted. Lack of dialysis provided the need and the production of urine was an immediate visible marker of transplantation success. Work was undertaken for the other solid organs, but the technical aspects were more challenging than for kidney transplantation. Early progress in kidney transplantation was related to the technical ease of the kidney transplantation surgery compared with that of others; the immunologic problems hampered progress until the development of the immunosuppressive agent azathioprine. The first successful human kidney transplantation was in 1954.1 It avoided the need for immunosuppression because it was a live donor kidney transplant exchanged between identical twins; this case was proof of concept that solid organ transplantation could successfully be achieved. The field of kidney transplantation was further fueled by the U.S. government underwriting the support of patients with end-stage renal disease, which fostered advances in kidney transplantation and hemodialysis. The parallel development of the concept of brain death2 resulted in a potential source of donor organs for the nascent field of transplantation.

The first human liver transplantation was performed in 1963 by Dr. Thomas Starzl. The patient suffered from biliary atresia, had coagulopathy, and did not survive the surgery.3 Additional attempts in Berlin, Boston, and Paris were also unsuccessful. Subsequent initial successes in orthotopic liver transplantation were in patients with liver cancer. These patients had less portal hypertension and relatively straightforward surgery but were not long-term survivors secondary to recurrent disease, technical problems, and lack of adequate immunosuppression.

In the early 1980s, liver transplantation in the United States was limited to a handful of programs; initial results were poor, with less than 30% 1-year survival. A major advance came with the clinical introduction of cyclosporine for immunosuppression in solid organ transplantation.4 Its use in liver transplant recipients allowed for further developments in this field.

As success in liver transplantation increased, more centers initiated programs and increasing numbers of patients availed themselves of this therapy. In attempts to provide timely transplantation to patients with the greatest need, local regional and national distribution schemes were developed and allocation to patients on the waiting list became based on need rather than on time on the list (see later, “Organ Shortage, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease, and Liver Distribution”).

Indications and Contraindications

Indications

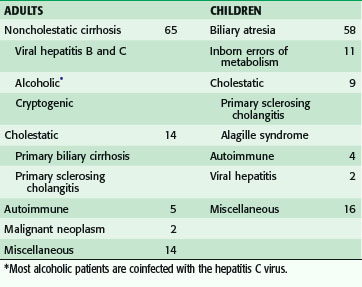

As the outcome of liver transplantation has improved, the indications have expanded to include any patient with compromise of life from chronic liver insufficiency, chronic liver disease with acute decompensation, acute liver failure, and enzyme deficiencies (Table 27-1). Liver transplantation is also indicated to a limited degree for patients with primary liver tumors.

The first issue regarding candidacy for transplantation is whether a given patient would benefit from liver replacement. The second issue that must be addressed is whether the patient can withstand the challenge of a liver transplantation surgery. Compromise in cardiac or pulmonary function may prohibit the patient as a candidate. In some cases, failure of an additional organ system may dictate combination transplantations. Although kidney-liver transplantations are relatively common, heart-liver and lung-liver transplantations are rarely performed.5

Fulminant Hepatic Failure

In addition to encephalopathy, the disease is characterized by jaundice, coagulopathy, metabolic acidosis, and renal insufficiency. Encephalopathy may progress to coma. Once a patient reaches stage 4 encephalopathy, the rate of successful treatment without transplantation ranges from 5% to 20%, depending on the cause.6 Its most common cause in the United States and England is acetaminophen overdose,7 either accidental or intentional. In Asia, acute hepatitis from hepatitis B viral infection is the most common cause.8 In a significant number of cases the specific cause is unknown. Acetaminophen overdose carries a relatively good prognosis without transplantation if the metabolic functions related to the liver are maintained.

Hepatitis C and Liver Transplantation

Hepatitis C infection recurs after transplantation because the virus resides in tissues other than the liver. The aggressiveness of the recurrent hepatitis C after liver transplantation cannot be predicted; risk factors include donor age, treatment for acute rejection, and level of hepatitis C viremia at the time of transplantation.9 Another factor that predicts hepatitis C reinfection severity after transplantation is the treatment for rejection after transplantation (with additional steroids or antilymphocyte preparations).10 Transplantation of a liver from a donor older than 40 years is associated with a greater risk of recurrent cirrhosis than from a younger donor. Hepatitis C treatment with interferon and ribavirin is effective in approximately 50% of patients prior to transplantation and in 30% to 40% of patients post-transplantation.11 It has been suggested that pretransplantation treatment of patients for whom a live donor has been identified can be followed by planned transplantation as a rescue therapy. The success of pretransplantation treatment of hepatitis C depends on the level of viremia in the recipient. The limitations to treatment with interferon and ribavirin are bone marrow suppression and the systemic inflammatory response associated with their administration. In cirrhotic patients, splenic sequestration of platelets and neutrophils limit preoperative therapy with interferon and ribavirin.

Chronic hepatitis C infection is also an important risk factor for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). It has been estimated that the current rise in the incidence of HCC reflects the United States hepatitis C epidemic of the 1960s through 1970s.12

Hepatitis B

Chronic hepatitis B infection is the most common cause of chronic liver disease in endemic regions of Asia and Africa, and the most common cause of death from hepatitis worldwide.13

Primary Biliary Cirrhosis

Primary biliary cirrhosis is a form of autoimmune cholestatic liver disease, with inflammatory injury to the bile ducts. It is a chronic cause of hepatic insufficiency and is characterized by autoimmune markers and some response to immunosuppressants.14 This disease is more common in females. The disease may recur years after transplantation but its recurrence is unlikely to progress to the need for retransplantation.

Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis

This is an autoimmune disease that is more frequent in males. It progresses over the years to a cholestatic picture associated with scarring of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts. The disease is associated with ulcerative colitis in approximately 90% of patients. In a small number of patients (<10%), the process is associated with cholangiocarcinoma.15 The bile duct involvement in primary sclerosing cholangitis dictates the use of choledochojejunostomy in patients undergoing liver transplantation. Primary sclerosing cholangitis may also recur after transplantation, although its recurrence is rare.

Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis16 reflects a pending epidemic of liver disease associated with the epidemic of obesity and metabolic syndrome in the United States. Fatty infiltration of the liver, with inflammation and subsequent injury and fibrosis, are the histologic features. The associated metabolic syndrome and diabetes dictate evaluation of the coronary arteries of these potential recipients. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis may recur after transplantation.

Contraindications

Systemic infections are considered contraindications to transplantation and uncontrolled bacterial and fungal infections are absolute contraindications to transplantation. Infections in the liver, such as cholangitis, may be an exception to this rule. HIV infection is considered by some groups to be a contraindication but several studies have shown outcomes comparable to those of matched control patients if the virus is controlled.17

Failure of another organ may be a contraindication to transplantation if that organ cannot be replaced or expected to recover. Kidney transplantation accompanies liver transplantation in 5% of cases. On occasion, liver-heart transplantation is performed for diseases such as amyloidosis; combined liver-lung transplantation for diseases such as cystic fibrosis has been performed in rare circumstances.5

Patients with chronic liver disease can develop pulmonary manifestations of their liver disease. Portopulmonary hypertension is considered a contraindication with persistent pulmonary artery pressures higher than 50 mm Hg in the presence of elevated pulmonary vascular resistance.18 Hepatopulmonary syndrome becomes a contraindication to transplantation when the PaO2 does not demonstrate marked improvement with the administration of 100% oxygen.19

Inability to care for the transplanted organ adequately because of continued drug or alcohol abuse or lack of commitment to immunosuppressive drugs is considered a contraindication to transplant. Continued commitment to immunosuppressive drugs is difficult to assess pretransplantation; in some series, noncompliance has been reported to be up to 35%.20

Metastatic HCC is considered an absolute contraindication to transplantation, related to poor outcome from metastatic disease. The risk of metastatic disease after liver transplantation is dependent on the size and number of HCC(s) in the liver. The Milan criteria for liver transplantation for HCC (single nodule <5 cm, or less than three nodules, the largest of which is <3 cm) are used to predict the risk of recurrent disease after transplantation. Patients who meet these criteria have a risk of recurrence that is less than 20% whereas patients outside the criteria have a recurrence rate of approximately 60%.21 The Milan criteria are currently used to define acceptable candidates for transplantation in the United States; patients who meet Milan criteria are given extra priority for transplantation. There is a controversy regarding transplantation for patients outside the Milan criteria and there is an interest in finding other methods of identifying those patients who have a low recurrence risk after transplantation. In the future, molecular biomarkers may prove reliable for selecting patients who will benefit from transplantation.

Organ Shortage, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease, and Liver Distribution

The decision of whether a patient is a candidate for transplantation and what priority a given patient should have is dictated in part by the relative shortage of deceased donor donors. Despite substantial governmental and community efforts, the needs of the 15,000 patients awaiting transplantation are not met by the approximately 5000 or so donors.22

The current system of liver distribution in the United States depends first on the level of the local organ procurement organization, then to the 11 United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) regions, and then shared on a national basis. A patient’s priority on the waiting list is based on his or her medical status as determined by the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score, which reflects the likelihood of death within 3 months. The MELD score assigns points that reflect the severity of liver disease. The score is based on a formula that considers bilirubin and creatinine levels and the international normalized ratio (INR).23

Model for End-Stage Liver Disease Formula

The components of the MELD score were chosen because they represent objective criteria that can be reviewed and verified as compared with ascites and encephalopathy, which were used previously (as part of the Childs-Pugh score) but are subjective and cannot be readily verified. The use of the MELD score to determine liver distribution has led to a significant decrease in the rate of death of potential recipients on the waiting list because it allows livers to be directed to the sickest patients. Patients with a high MELD score at the time of transplantation have slightly poorer survival following transplantation (Table 27-2).

Table 27-2 Concordance With 3-Month Mortality

| SCORE | CONCORDANCE (%) | 95% CONFIDENCE INTERVAL (%) |

|---|---|---|

| MELD | 0.88 | 0.85, 0.90 |

| Childs-Turcote-Pugh (CTP) | 0.79 | 0.75, 0.83 |

For patients with low MELD scores, less than 15, the risk of death while waiting for transplantation is less than the risk of death after transplantation.24 The current allocation system therefore discourages transplantation of patients with MELD scores less than 15 by allocating a liver to all the higher MELD score patients in the region before allowing local use in patients with scores less than 15. These last two concepts, that sicker patients have a greater risk of poor outcome after liver transplantation and that relatively healthy patients, whose outcomes are worse with transplantation than if they remained on the waiting list, suggest that both pretransplantation and posttransplantation outcomes should be considered in the allocation of livers. Currently, the use of the MELD score only weighs the pretransplantation outcomes, and death on the waiting list has been reduced since the initiation of MELD. It has been proposed that the MELD score be replaced as a means to distribute organs with a system that determines potential survival benefit after transplantation, or a combination of survival benefit prior to and after transplantation for patients with chronic liver disease.25

For some patients, the risk of death or dropout from the list may not be reflected in the laboratory values in the MELD score. For example, patients with HCC benefit from transplantation, even when their laboratory test results are normal. To allow transplantation, an exception is made and additional MELD points are assigned to these patients.26 This approach is used to transplant these patients prior to their tumors becoming so extensive that patients fall outside the limits of criteria for liver transplantation. It is also used for diseases such as amyloidosis.

Pediatric donors are distributed to pediatric patients preferentially. The scoring used in pediatric patients is referred to as the pediatric end-stage liver disease (PELD) score.27

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree