INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

One perspective on the question of “Indications” for an open segmental resection is when to choose open rather than VATS. A second perspective is when to select segmental resection compared to lobar resection or wedge resection. For the most part the first question, open versus VATS segmentectomy, is similar to the open versus VATS lobectomy question. VATS segmental resection is technically more challenging but is our preference whenever possible. Uncertainty of anatomic location of the lesion either before or during a VATS procedure is a common reason for deciding to perform an open procedure. Regarding the question of extent of resection, current evidence supports the use of lobectomy for most patients. When anatomically favorable, in patients with adequate lung function, we would preferentially choose segmental resection for solid tumors less than 1 cm, or for ground glass (GGO) lesions less than 2.5 cm. With GGO lesions, one must take extra care planning the line of resection, as the lesion may not be palpable to guide adequacy of surgical margin, even during open resection. When otherwise suitable for VATS resection, we have found the CT-guided placement of a wire coil for fluoroscopic assurance of resection margin to be helpful. For patients with compromised lung function, our preferred approach is to use VATS surgery to minimize short-term risk. The long-term benefits of segmental resection over lobectomy are less than one might expect, at least in terms of FEV1. An increasingly common indication for segmental resection is the patient with multiple lung tumors, either synchronous or metachronous. In this setting, it is wise to consider segmental resection if adequate margins (at least equivalent to the size of the tumor) can be obtained. A wedge resection, by comparison, for nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is inadequate as it carries a higher local recurrence rate, higher cancer-associated mortality, and worse overall survival.

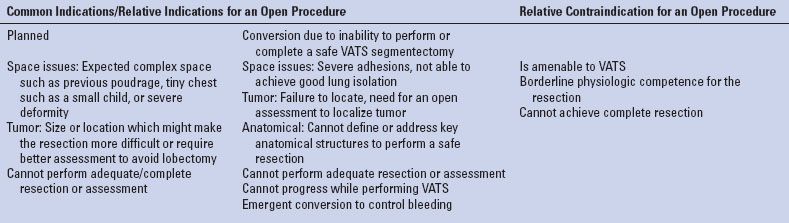

TABLE 25.1 Choosing an Open Approach—Common Indications and Contraindication

No randomized controlled trial demonstrated a benefit for metastasectomy, nevertheless the cumulative experience supports resection of oligometastatic disease. An open approach has been advocated in this specific setting to increase the yield of detecting additional small metastases. As imaging studies improve, the yield decreases and the significance of these additional tiny lesions is unknown. Thus our preference in this setting is VATS wedge resection where possible. However, for more centrally located metastases we favor segmental resection over lobectomy wherever possible in view of the possibility of future recurrence.

Other common indications for segmentectomy include congenital, infectious, and inflammatory disorders.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Diagnosis

It is recommended to strive for a tissue diagnosis before going ahead with a segmentectomy, as dissection of the vessels does carry some risk. When tissue diagnosis was not achieved in advance, in some cases it may be possible to perform wedge resection as diagnostic biopsy during the operation. But in some cases the better judgment is to simply proceed with segmental resection, as a preliminary wedge biopsy may cause significant distortion.

Staging

Preoperative staging should be undertaken for any resection for malignancy. Intraoperative staging should be especially thorough with a liberal use of intraoperative quick sections to determine if segmental resection is still an appropriate choice.

Is the Disease Technically Resectable by Segmentectomy and at What “Price”?

Prior to the procedure the imaging should be reviewed to assess the tumor, the anatomical structures, and their relations to each other. Special attention must be paid to the location of the lesion in the lung to assess whether segmentectomy can be performed with adequate margins and without compromising adjacent segments. An attempt to assess function of the segment to be removed should be made, with attention to features such as high diaphragm, regional emphysema or atelectasis, and correlation with V/Q scans.

Physiologic Competence

The inability to comfortably walk up a single flight of stairs is the point where one wonders if the patient can tolerate any more than segmentectomy from a respiratory point of view. Lung perfusion studies, formal pulmonary function tests, and extensive cardiopulmonary exercise testing can further assess marginal patients. The final assessment of ability to withstand limited lung resection is a nuanced decision with no absolute cutoffs. It should take into consideration the location of the tumor, the function of that segment and function of both lungs, and intangibles such as patient’s personality type. The potential need for an extended resection/possible lobectomy or pneumonectomy and the ability of the patient to tolerate it should be specifically evaluated. All other comorbidities should be assessed and optimized, such as a short course of steroids for COPD and smoking cessation. The need for an ICU bed and special postoperative issues such as mobility and social issues should be assessed in advance.

A thorough discussion with the patient/family detailing the risks and benefits of the proposed procedure should be held. The patient should be well educated about the procedure and perioperative period. There should be clear communication with anesthesia, ICU, nursing, and other support caregivers for best patient care.

SURGERY

SURGERY

Anatomical Considerations

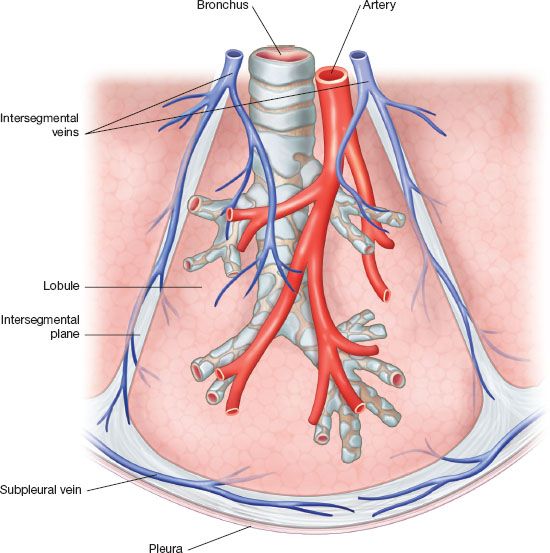

The relevant lobar anatomy is described in Chapter 15. Within the lobe, the anatomic unit of the lung is the bronchopulmonary segment (Fig. 25.1). Each possesses its own bronchus, pulmonary arterial, venous, and lymphatic system and as such it can be removed individually without disturbing the function of adjacent segments. The segments are constant in their topographic shape and each is pyramidal in shape with the apex toward the center and base toward the pleural surface. They are surrounded by the connective tissue septa, which are continuous with the pleural surface. At the center of the segment runs a segmental bronchus, which usually further divides distally. A corresponding segmental PA branches to accompany the segmental bronchus. One main segmental vein drains each segment but as opposed to the bronchus and artery the veins run in an intersegmental plane. Thus, the veins mark the boundaries of each segment. The drainage pathway of the lymphatic is from subpleural lymphatic to larger channel running along the segmental arteries and bronchi and then to subsegmental and segmental lymph nodes. The most reliable landmark of the segment is the bronchus; it is rarely anomalous.

Figure 25.1 Anatomy of the bronchopulmonary segment The bronchopulmonary segment is pyramidal in shape. The apex of the pyramid tip is oriented to the center of the lung. The bronchus runs at the center of the segment and is accompanied by a pulmonary artery segmental branch, which runs along its posterior surface. Each segment is drained by one major venous segmental branch. The segmental veins follow the intersegment plane, which marks the boundaries of each individual segment. An open fracture technique takes advantage of this nature to allow dissection along the intersegment plane. There is substantial collateral drainage for each segment allowing for an extended stapler-assisted segmentectomy.

Equipment

An open segmentectomy requires a standard surgical tray identical to a lobectomy tray. While performing a VATS segmentectomy adequate equipment for open thoracotomy should still be available in case of an emergency conversion. Due to the nature of operating in a deep cavity we cannot overemphasize the need for a good headlight. Using the thoracoscopic equipment in an open procedure can facilitate lighting of the surgical field and can enable viewing difficult areas such as the apex the of the chest wall. We never pass off the thoracoscopic equipment after conversion to open thoracotomy and respectively have available a separately wrapped flexible pleuroscope during open cases.

Anesthesia and Preparation for Surgery

A team briefing is performed with the patient awake to review side, planned surgery, and preoperative medications. Lung isolation is preferably achieved by a double-lumen tube, although a bronchial blocker is acceptable and easier to place in smaller patients. We prefer a left-sided double-lumen tube and verify its position by a pediatric bronchoscope after intubation and again after positioning the patient. The remainder of the preoperative preparation is similar to that for upper lobectomy (Chapter 15).

Positioning and Incision

Posterolateral thoracotomy is our standard approach. We strive to perform a “semimuscle-sparing thoracotomy” by dividing latissimus but mobilizing the serratus anterior muscle from the chest wall. Making an effort to preserve the muscle allows better chest wall integrity and early perioperative shoulder function and it may become beneficial if a muscle flap will be considered, however, the rate of seromas is reported to be increased. Depending on the magnitude of the operation, the latissimus can be retracted, divided, or mobilized for possible use as a major flap. The patient is positioned in the right lateral decubitus position, an axillary roll is placed just caudal to axilla to protect the brachial plexus, the table is flexed between the 12th rib and the upper pelvis and reverse Trendelenburg positioning is used to flatten the flank and open the intercostal spaces. The patient is stabilized by a bean bag covered superficially by a gel pad and stiffened by applying suction. It should be hugging the patient bilaterally, away from the axilla and support the pelvis as well. All pressure points should be well padded. The sterile field should include the lateral border of the spine up to level of the neck allowing the extension of the thoracotomy posteriorly if required. At the anterior border it should include the sternum. Care must be taken to ensure the epidural catheter is not directly caught by the sterile covers or it can be inadvertently removed at the end of the case.

The chest is entered at the level of the fifth intercostal space. This correlates with the oblique fissure. For a better exposure one can shingle a posterior segment of the rib or completely resect a rib using the subperiosteal plane. This can facilitate entering a complicated pleural space such as when the lung is severely adherent to the chest wall. Occasionally starting with an extrapleural dissection can further facilitate this. If the use of an intercostal muscle flap is to be expected than harvesting the muscle should be done at this stage allowing safe handling and protecting its blood supply.

After final positioning, verify that all lines, tubes, and devices are well placed and still working.

Intraoperative Assessment

Generally speaking, we approach most patients with either planned thoracotomy or planned VATS and a conversion rate, perhaps somewhat higher than for lobectomy (<5%). However, thoracoscopy can be performed before going ahead with a thoracotomy. It is less invasive and may reveal findings encouraging for proceeding with VATS or alternatively may clearly mandate the need for an open procedure. On rare occasions it unfortunately might reveal advanced disease where segmentectomy is not appropriate. Once thoracoscopy equipment is added, it can be helpful in an open approach for lighting and overcoming blind spots.

Full assessment is usually achieved after lung mobilization. The extent of the disease and location should be assessed visually, by palpation and with the use of quick section as needed. For curative intent NSCLC resection lobar, hilar, and mediastinal nodes should be addressed and sent intraoperatively for pathology if suspicious. It should be emphasized that intraoperative lymph nodes’ sampling is one of the advantages and benefits of a surgical approach as opposed to other local treatments such as external radiation. The intraoperative finding of lobar/N1 disease should strongly advocate for performing a lobectomy. However if the patient is unable to tolerate a lobectomy a less favorable alternative would be performing segmentectomy with radical lymphadenectomy and consideration of post-op adjuvant treatments. Another possible alternative would be to abort surgery and refer for chemo and possible radiation treatments. The intraoperative finding of N2 disease should either suggest lobectomy, lymphadenectomy, and adjuvant treatment or aborting and referring to chemo and possible radiation. For patients with metastatic disease the finding of positive mediastinal lymph nodes might exclude the patient from surgery.

Stapler-assisted Segmentectomy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree