INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Because none of the available treatments can correct the underlying disease in patients with achalasia, the foundation of therapy is palliative and centers on relieving esophageal outlet obstruction while minimizing postmyotomy gastroesophageal reflux. Pneumatic dilation and surgical myotomy are the procedures most commonly performed for achalasia. In current practice, pharmacologic therapies, such as botulinum toxin and smooth muscle relaxants, while minimizing the side effects of surgery, are reserved for patients who are unable or unwilling to undergo surgical treatment or pneumatic dilation. A recent meta-analysis suggested that surgical myotomy is superior to pneumatic dilation in achieving long-term therapeutic success, although the included studies were inadequately powered and exhibited a large degree of heterogeneity in study design and likely in surgical techniques. The most recent European multicenter, randomized controlled study to compare pneumatic dilation with laparoscopic myotomy demonstrated that the short-term therapeutic success rate (up to 2 years) was equivalent between the groups. In this study, the dilation was initially performed using a 35-mm balloon and esophageal perforation occurred in 30% of patients. Subsequently, the protocol was modified and the primary dilation was performed using a 30-mm balloon. The esophageal perforation rate in the dilation group was 4% compared with 12% in the myotomy group. Due to recurrent symptoms, 24% of the dilation group required additional dilations or surgical myotomy, whereas only 14% of the myotomy group required dilation. Up to 20% of the myotomy group had evidence of postmyotomy gastroesophageal reflux. These findings suggest that the treatment algorithm for achalasia requires further modification and individualization in order to improve the outcomes, regardless of which procedure is employed. Although pneumatic dilation is the most effective nonsurgical option to treat achalasia, it is a process requiring several interventions that result in submucosal microhemorrhage and fibrosis, and in our most recent review, we noted an increased risk of mucosal perforation during surgical myotomy. In addition, younger patients (<40 years) tend to require more dilations for recurrent symptoms, thus we prefer to manage younger patients preferentially with surgical myotomy.

The Heller myotomy was first described as two parallel myotomies in 1913 and was subsequently revised to a single anterior myotomy in 1923. With the advancement of minimally invasive surgical techniques over the last two decades, laparoscopic myotomy has become the first-line treatment option at most centers in the United States. Prior interventions (such as dilation or botulinum toxin injections), the presence of a sigmoid esophagus, long duration of symptoms, and a low resting LES pressure may be associated with an increased risk of failure with laparoscopic myotomy. In addition, preexisting daily chest pain is a predictor of therapeutic failure and likely indicates vigorous achalasia with simultaneous esophageal contractions as a cause contributing to the symptom complex.

Since Richards et al. demonstrated a significant benefit with the addition of a partial fundoplication to reduce postmyotomy gastroesophageal reflux symptoms, the majority of surgeons have incorporated a Dor or a Toupet partial fundoplication as an integral component of the procedure. In this chapter, the technique of the laparoscopic Heller myotomy combined with laparoscopic partial fundoplication (Dor or Toupet) is described.

Sigmoid Esophagus

Sigmoid esophagus is a dramatically dilated and tortuous thoracic esophagus that reflects long-standing achalasia and chronic obstruction. Although somewhat controversial, several authors have demonstrated good outcomes in patients with achalasia and a sigmoid esophagus who had undergone myotomy and a partial fundoplication. Others recommend esophagectomy for these patients.

DIAGNOSIS AND PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

DIAGNOSIS AND PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Achalasia should be suspected for any patient with dysphagia and regurgitation of undigested food and saliva. The diagnosis is based on clinical symptoms, barium esophagram, and esophageal manometry. During the workup, it is crucial to exclude any organic lesions, such as esophageal cancer, that may cause pseudoachalasia. Patients with pseudoachalasia may be older and have a quickly progressing dysphagia and remarkable weight loss. If pseudoachalasia is still suspected after a meticulous workup, endoscopic ultrasound and/or CT scan should be performed to rule out external compression or an intramural neoplastic process. It should be noted that pseudoachalasia can follow long-standing dysphagia from an excessively tight anti-reflux wrap or can occur as a component of a paraneoplastic syndrome, and the treatment of the primary tumor (i.e., colon cancer) can improve the symptoms of achalasia.

In patients with achalasia, a barium esophagram typically demonstrates a dilated esophagus with a smooth distal tapering, and this finding is frequently described as a “bird’s beak” narrowing at the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ). It should be noted that esophageal dilation may not be present in the early stages of achalasia. Upper endoscopy may show a dilated esophagus with undigested, retained food. A feeling of a “pop” will often be experienced by the endoscopist when traversing the GEJ with the endoscope, which further supports the diagnosis. Endoscopy is also important to rule out the presence of esophageal malignancy and/or Barrett’s esophagus and to remove the retained fluid and the debris from the esophagus prior to surgery.

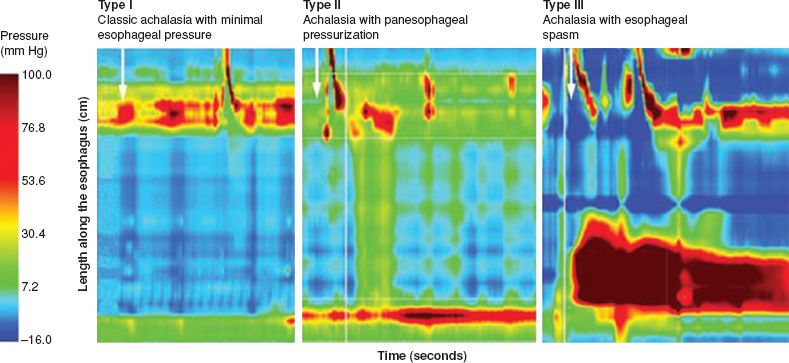

Esophageal manometry is the gold standard in making the diagnosis of achalasia, typically demonstrating absent or incomplete relaxation of LES and an aperistaltic esophageal body. The LES resting pressure is often elevated from baseline; however, many patients have relatively normal LES resting pressure but do not demonstrate complete relaxation upon deglutition. The aperistalsis may be characterized by low-amplitude (<30 mm Hg), simultaneous mirror image (isobaric) waves due to a common cavity phenomenon. Vigorous achalasia is a rare variant of achalasia, which is characterized by repetitive simultaneous contractions with no relaxation of the LES and can be associated with chest pain. Because the interpretation of manometry is sometimes difficult in patients with a dilated or a food-filled esophagus, the data should be interpreted as a component of the entire clinical picture. Recently, Pandolfino et al. categorized patients with achalasia into three groups based on the findings exhibited on high-resolution manometry (HRM): Achalasia without esophageal pressurization (type I, classic), achalasia with esophageal compression or compartmentalization in the distal esophagus >30 mm Hg (type II), and achalasia with spastic contractions (type III) (Fig. 14.1). Logistic regression analysis demonstrated that a type II pattern on HRM is a predictor of positive treatment response, whereas type III is associated with negative treatment response, suggesting that this classification system may be useful in predicting the outcomes and tailoring therapeutic options.

Figure 14.1 Subclassification of achalasia based on high-resolution manometry. Type I: Classic achalasia with minimal to no esophageal pressurization; Type II: Achalasia with panesophageal compression or compartmentalization in the distal esophagus >30 mm Hg; Type III: Achalasia with spastic contractions. (Reproduced from: Eckardt AJ, Eckardt VF. Treatment and surveillance strategies in achalasia: An update. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol

Prior to surgery, the possibility of the need for subsequent interventions due to primary treatment failure should be explained, especially in patients with preexisting chest pain, prior dilations or botulinum toxin injections, a sigmoid esophagus, and long duration of symptoms. Preoperatively, the patient should be maintained on a liquid diet for 3 days to reduce the amount of undigested food in the esophagus. Rapid sequence intubation with cricoid pressure (Sellick’s maneuver) should be uniformly employed to minimize the risk of aspiration.

SURGERY

SURGERY

Positioning

The operation is performed under a general anesthesia in a split-legged position. Sequential compression devices are routinely applied to prevent deep venous thrombosis. The patient’s knees are supported and a footboard is placed to prevent patient sliding when the table is placed in a steep reverse Trendelenburg position. The surgeon stands in between the patient’s legs, and the assistant stands on the left side. Alternatively, the surgery can be performed with the patient in a supine position and the surgeon standing on the right side of the table.

The operation is performed under a general anesthesia in a split-legged position. Sequential compression devices are routinely applied to prevent deep venous thrombosis. The patient’s knees are supported and a footboard is placed to prevent patient sliding when the table is placed in a steep reverse Trendelenburg position. The surgeon stands in between the patient’s legs, and the assistant stands on the left side. Alternatively, the surgery can be performed with the patient in a supine position and the surgeon standing on the right side of the table.

Upper endoscopy is performed. Care is taken not to insufflate too much air and to decompress the stomach thoroughly after the endoscopic examination. The endoscope can be maintained in the proximal esophagus for evaluation following myotomy.

Upper endoscopy is performed. Care is taken not to insufflate too much air and to decompress the stomach thoroughly after the endoscopic examination. The endoscope can be maintained in the proximal esophagus for evaluation following myotomy.

Port Placement

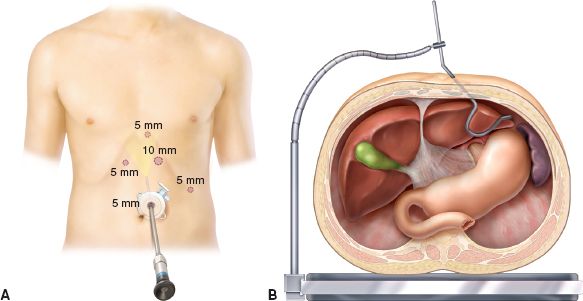

We first create pneumoperitoneum by inserting a blunt port using a cut-down technique; others describe inserting a Veress needle in the left upper abdomen close to the costal margin. A 5-mm port is subsequently placed in the left paramedian location 3 to 5 cm above the umbilicus and the pneumoperitoneum is maintained at 15 mm Hg. This 5-mm port is used for the camera which is controlled by the assistant’s left hand. A 5-mm 30-degree laparoscope is introduced through this port, and exploratory laparoscopy is performed (Fig. 14.2A). We use VersaStep bladeless trocars for all ports (Covidien Surgical, Mansfield, MA).

We first create pneumoperitoneum by inserting a blunt port using a cut-down technique; others describe inserting a Veress needle in the left upper abdomen close to the costal margin. A 5-mm port is subsequently placed in the left paramedian location 3 to 5 cm above the umbilicus and the pneumoperitoneum is maintained at 15 mm Hg. This 5-mm port is used for the camera which is controlled by the assistant’s left hand. A 5-mm 30-degree laparoscope is introduced through this port, and exploratory laparoscopy is performed (Fig. 14.2A). We use VersaStep bladeless trocars for all ports (Covidien Surgical, Mansfield, MA).

The second port (10 mm) is placed in the left midclavicular line, 2 cm below the left costal margin under direct visualization. This access is used for the surgeon’s right hand. The third port (5 mm) is then placed within the left anterior axillary line along the left costal margin and is used for the assistant’s right hand. The fourth port (5 mm) is placed immediately to the left of the xiphoid process. A Nathanson liver retractor (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN) is inserted through this port and secured with a table-mounted holder to retract the left lateral segment of liver superiorly, exposing the diaphragmatic hiatus (Fig. 14.2B). The last port (5 mm) is placed 2 to 3 cm below the right costal margin, immediately to the anatomic right position of the falciform ligament and is used for the surgeon’s left hand.

The second port (10 mm) is placed in the left midclavicular line, 2 cm below the left costal margin under direct visualization. This access is used for the surgeon’s right hand. The third port (5 mm) is then placed within the left anterior axillary line along the left costal margin and is used for the assistant’s right hand. The fourth port (5 mm) is placed immediately to the left of the xiphoid process. A Nathanson liver retractor (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN) is inserted through this port and secured with a table-mounted holder to retract the left lateral segment of liver superiorly, exposing the diaphragmatic hiatus (Fig. 14.2B). The last port (5 mm) is placed 2 to 3 cm below the right costal margin, immediately to the anatomic right position of the falciform ligament and is used for the surgeon’s left hand.

Figure 14.2 A: Port placement. Five-port technique is used. B: Placement of Nathanson liver retractor. The left lateral segment of liver is retracted superiorly to expose the diaphragmatic hiatus.