IVC Filter Placement

ELIZABETH ANDRASKA, PETER K. HENKE, and JOHN RECTENWALD

Presentation

A 65-year-old woman presents to the ED with pain and swelling in her left leg. This patient has a medical history significant for left femur fracture, which was repaired 2 months ago. She also has a history of left leg tibial vein deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and had been taking chronic warfarin. However, she suffered a recent 4U gastrointestinal bleed and now cannot take anticoagulation for at least 6 weeks. She has no family history of DVT.

On physical exam, the left leg is noted to be warm and swollen. The patient reports acute pain and tenderness when asked to walk across the examination room. She undergoes a duplex ultrasound scan of each lower extremity. She is discovered to have a new acute, occluding DVT in her left external iliac vein.

Differential Diagnosis

In a patient with such a classic presentation, a DVT workup and immediate ultrasonography is imperative. In addition to DVT, a possible pulmonary embolism (PE) must be considered in the differential diagnosis. However, most patients who present with such symptoms will not have a DVT. A differential diagnosis for lower extremity pain and swelling includes a muscle or orthopedic injury, lymphatic obstruction, venous insufficiency, cellulitis, or Baker’s cyst. Patients who present with bilateral leg swelling may need to be evaluated for potential systemic causes of leg swelling such as cirrhosis, congestive heart failure, or nephrotic syndrome.

Workup

DVT and PE, collectively referred to as venous thromboembolism (VTE), is a common clinical problem. Timely diagnosis and therapy is necessary to avoid embolism and potentially death. Many tests can be done to assess VTE risk; however, a D-Dimer test in conjunction with a Well’s score can reliably determine pretest probability of VTE. Additionally, duplex ultrasonography with gray-scale imaging to detect luminal thrombus and Doppler flow to assess the flow within the vessel should be performed on each extremity to assess the presence and extent of possible DVT. If suspicion for PE remains high, computed tomography angiography has replaced pulmonary angiogram and is now the gold standard for diagnosis of PE.

This patient was found to have an elevated D-Dimer of 4.5 (normal 0.4 to 2.5) and a Well’s score criteria of 3 due to recent trauma and medical history significant for DVT. As stated, the duplex ultrasound study showed a DVT in the left external iliac vein.

Diagnosis and Treatment

The gold standard for treatment of VTE is anticoagulation therapy. However, in certain patient populations, anticoagulation therapy is contraindicated. Contraindications to anticoagulation include patients who cannot be safely anticoagulated such as those with brain metastasis, severe thrombocytopenia, or active bleeding at the time of diagnosis. Patients who have failed or have poorly controlled anticoagulation therapy or those who develop a complication due to anticoagulation therapy are also candidates for placement of an IVC filter. Less strong indications include those at high risk for bleeding or falls while on anticoagulants. In these patients, an inferior vena cava filter should be considered to prevent a fatal PE. Patients who are at high risk for bleeding may also be contraindicated for anticoagulation therapy. Risk factors for bleeding include age greater than 65, previous bleeding, thrombocytopenia, antiplatelet therapy, recent surgery, previous stroke, diabetes, anemia, cancer, renal failure, and liver failure. Both permanent and retrievable optional filters are available. In patients with acute, short-term contraindication for anticoagulation, a retrievable filter is a reasonable choice.

Although controversial, IVC filters are used as prophylaxis in high-risk individuals. In one large review, IVC filters were indicated both as prophylaxis in high-risk individuals (58%) and therapeutically in patients with a diagnosed acute proximal venous thrombus or VTE and contraindicated for anticoagulation therapy (42%). Individuals that may benefit from IVC filter prophylaxis include high-risk trauma patients, orthopedic and neurosurgical patients, and cancer patients. However, strong evidence for prophylactic filters is lacking.

This patient’s indication for a filter is an anticoagulation complication as well as need for PE protection for at least 1 to 3 more months. Given the limited time frame required for an IVC filter, a retrievable IVC filter would be indicated for this patient.

Surgical Approach

There are many types of IVC filters. When deciding on which one to place, one should consider its ability to trap clot without compromising venous return within the cava and the ease of placement and removal. With this patient, a Denali vena cava filter (Bard, Tempe, AZ) was chosen due to a reasonable efficacy and safety profile. This particular filter should only be used in IVCs less than 30 mm.

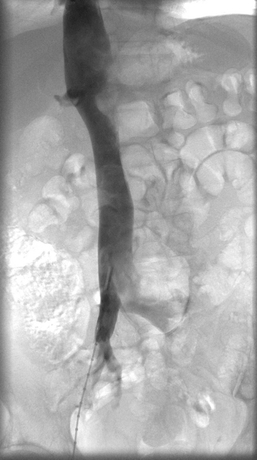

A venogram is performed first. The IVC can be accessed from either femoral vein or jugular vein. The right femoral vein is most often used to access the site because it provides direct access to the IVC and a straighter lie for filter, minimizing filter tilting. In patients that are hypercoagulable, have iliac vein thrombi, or are obese, the right internal jugular vein may be a less complicated access site. The procedure should be done under fluoroscopic guidance. To access the femoral vein, puncture the vein using the Seldinger technique. Next, a guidewire is advanced into the vein. The coaxial introducer sheath is introduced over the guidewire. Once in the common iliac vein, a vena cavagram is performed. It is important to assess for the presence of a duplicated cava, patency of the vessels, and any caval thrombus near the planned filter site as well as the landmarks for the renal veins (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1 Contrast venocavagram showing the iliac bifurcation and the renal veins; important landmarks for filter placement.