Intestinal Ischemia after AAA Repair

ENJAE JUNG and PATRICK J. GERAGHTY

Presentation

A 78-year-old man with history of diabetes, hypertension, and significant tobacco use is transferred from an outside hospital with a computed tomography (CT) confirming a diagnosis of a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). On initial presentation to the outside hospital, he was hypotensive with systolic blood pressure of 55 mm Hg. He is transfused two units of packed red blood cells and transferred to your institution. On arrival to the emergency department, his vital signs are as follows: temperature 37.1°C, heart rate 110 bpm, and blood pressure 73/39 mm Hg. He is awake and alert and complains of back pain. Review of his CT again confirms a contained ruptured infrarenal AAA with a moderate-sized left retroperitoneal hematoma. His aneurysm anatomy is suitable for an endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR), and he is taken emergently to the operating room. He undergoes an uncomplicated EVAR under local anesthetics with a modular, bifurcated graft from his infrarenal aorta to the iliac artery bifurcation. Both of his internal iliac arteries are diseased but patent and preserved. Postoperatively, he is taken to the surgical intensive care unit, where he remains hemodynamically stable. However, several hours later, you receive a call from his nurse that his urine output has decreased. He is also complaining of acute abdominal pain and a distended abdomen.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for decreased urine output in a postoperative patient is broad and includes bleeding, hypovolemia, cardiogenic shock, and sepsis. However, in the immediate postoperative period following an AAA repair, intestinal ischemia should be high on the differential. In addition, since this patient presented with a ruptured aneurysm, abdominal compartment syndrome from the hematoma and resuscitation should also be considered.

Workup

You go to examine the patient. He remains afebrile, and his vital signs are stable. He has a mildly distended abdomen that is tender to palpation especially in the left lower quadrant with voluntary guarding, but his abdomen is soft, and his bladder pressure is 8 mm Hg. Rectal exam is negative for gross blood, but a stool sample is guaiac positive. Laboratory testing is significant for a serum lactate level of 3.1 mmol/L and a leukocytosis of 16,000 cells/mL.

Discussion

No laboratory tests are pathognomonic of intestinal ischemia, and a high index of suspicion is essential. Findings potentially suggestive of ischemic colitis include persistent acidosis, leukocytosis, elevated lactate levels, and fluid sequestration. Patients may also have diarrhea or bloody bowel movement, but the classic finding of bloody diarrhea in the early postoperative period occurs in only about 30% of cases. Early identification is essential because progression to full-thickness necrosis is associated with a high mortality rate.

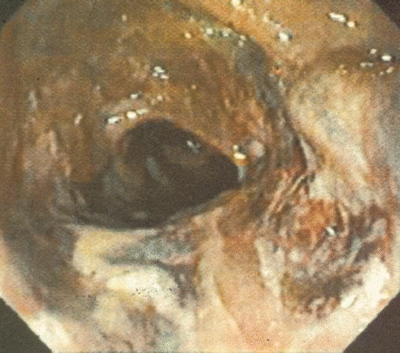

Fiberoptic colonoscopy is the diagnostic modality of choice to confirm the diagnosis and is important in guiding subsequent treatment since the severity of the ischemic insult widely varies. The mildest form of ischemic colitis results in ischemia limited to the colonic mucosa and submucosa. Patients may have symptoms of abdominal pain, ileus, distention, or bloody diarrhea and on endoscopy display patchy mucosal erythema, pallor, or ecchymosis. This is the most common form, and the disease resolves with adequate resuscitation and bowel rest alone. Extensive changes of mucosa with large confluent areas of involvement may indicate a more moderate form of ischemia. This involves ischemia of the muscularis and may eventually result in ischemic stricture formation. The most severe form of colonic ischemia involves transmural ischemia and colonic infarction. Fortunately, this is the least common form of colonic ischemia. Endoscopic changes include a flaccid or rigid colonic segment with mucosal friability, ulceration, and fissures (Fig. 1). Severe ischemic colitis requires resection of the infarcted bowel.

FIGURE 1 Endoscopic changes of severe ischemic colitis with evidence of mucosal friability and ulceration as well as patchy areas of necrosis.

Diagnosis and Treatment

The patient undergoes a bedside flexible sigmoidoscopy that shows boggy, erythematous mucosa with dusky patches circumferentially throughout the sigmoid colon, and rectum suggestive of mild to moderate ischemic colitis.

In elective open aortic reconstructions, clinically evident ischemic colitis develops in 1% to 3% of patients. Clinically insignificant colonic ischemia occurs more frequently. Routine endoscopic surveillance studies have reported an incidence of 4.5% to 11.4% in patients after elective AAA repair, whereas biopsy of the mucosa has identified ischemic changes in 30% of patients after aortic surgery, with half the patients having no macroscopically apparent ischemic changes. Fortunately, severe colon ischemia is rare after AAA repair, occurring less than 1% of the time, but it carries a high degree of morbidity and a significant mortality rate. Aneurysm rupture significantly increases the incidence of this complication, with as many as 60% of survivors demonstrating endoscopic evidence of colonic ischemia. Other risk factors for development of colonic ischemia after open aneurysm repair include hypotension, hypoxemia, prolonged aortic cross-clamp time, and operative trauma to the colon. Unlike open repair in which the onset is thought to occur from a global physiologic insult, the pathogenesis of colonic ischemia after endovascular repair is thought to be due to atheromatous embolization to the mesenteric microvasculature. Bilateral internal iliac artery occlusion and other factors, such as intraoperative hypotension, may have a possible secondary role.

In all forms of colonic ischemia, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy is routinely initiated. Mild ischemic injury isolated to the mucosa can initially be treated nonoperatively with bowel rest, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and fluid resuscitation, but close observation is warranted. Development of transmural ischemia, worsening sepsis, or peritoneal signs all require prompt surgical intervention (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Colon Ischemia after AAA Repair