21 Interventions for Failing Hemodialysis Access

Hemodialysis Access Anatomy

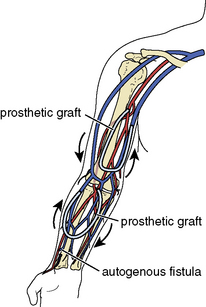

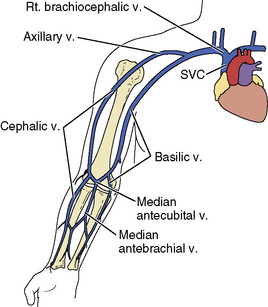

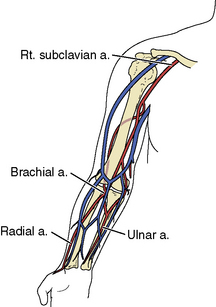

An autogenous arteriovenous access is surgically created by directly anastomosing a native outflow vein (Fig. 21-1) to a native inflow artery (Fig. 21-2), usually in the form of an end-to-side anastomosis. A prosthetic arteriovenous access is constructed by surgically interposing a segment of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) between a native artery and a native vein in either a straight or looped configuration. Common patterns include the brachial-cephalic configuration in the forearm or the brachial-basilic configuration in the upper arm (Fig. 21-3). For the purposes of this chapter, an autogenous arteriovenous access will be referred to as a fistula, a prosthetic arteriovenous access as a graft, and when mentioned together, both types will be referred to as accesses.

Figure 21-1 Venous anatomy of the upper extremity. Rt, right; SVC, superior vena cava; v, vein.

(Reprinted from Bittl JA. Catheter interventions for hemodialysis fistulas and grafts. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2010;3:1–11, with permission from Elsevier.)

Figure 21-2 Pertinent arterial anatomy of the upper extremity. a, artery; Rt., right.

(Reprinted from Bittl JA. Catheter interventions for hemodialysis fistulas and grafts. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2010;3:1–11, with permission from Elsevier.)

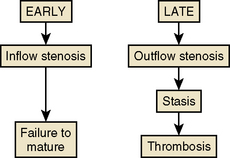

Mechanisms of Hemodialysis Access Failure

Two failure modes of fistulas and grafts are amenable to interventional treatment (Fig. 21-4). An inflow stenosis in newly placed fistulas may inhibit physiologic hypertrophy and maturation. An outflow stenosis in chronically used fistulas and grafts may cause high pressures and thrombosis. Although 50% of malfunctioning accesses ultimately undergo thrombosis, this is not the primary cause of failure. Instead, shear stress and fibromuscular hyperplasia of the outflow vein causes a progressively worsening stenosis, which then leads to stasis and eventual thrombosis (see Fig. 21-4).