Inflammatory Disorders

ENDOCARDITIS

Endocarditis is an infection of the endocardium, heart valves, or cardiac prosthesis that results from bacterial or fungal invasion.

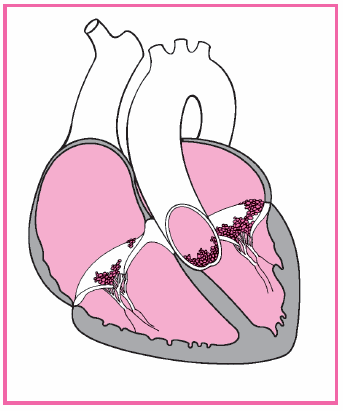

In patients with infective endocarditis, fibrin and platelets cluster on valve tissue and engulf circulating bacteria or fungi. This produces vegetation, which, in turn, may cover the valve surfaces, causing deformities and destruction of valvular tissue. It may also extend to the chordae tendineae, causing them to rupture, which leads to valvular insufficiency.

Sometimes vegetation forms on the endocardium, usually in areas altered by rheumatic, congenital, or syphilitic heart disease. It may also form on normal surfaces. Vegetative growth on the heart valves, endocardial lining of a heart chamber, or the endothelium of a blood vessel may embolize to the spleen, kidneys, central nervous system, and lungs.

Endocarditis can be classified as native valve endocarditis, endocarditis in I.V. drug users, or prosthetic valve endocarditis. It can be acute or subacute. Untreated, endocarditis is usually fatal. With proper treatment, however, about 70% of patients recover. The prognosis is worse when endocarditis causes severe valvular damage—leading to insufficiency and left-sided heart failure—or when it involves a prosthetic valve.

Pathophysiology

In endocarditis, bacteremia—even transient bacteremia after dental or urogenital procedures—introduces the pathogen into the bloodstream. This infection causes fibrin and platelets to aggregate on the valve tissue and engulf circulating bacteria or fungi that flourish and

form on fragile, wartlike vegetative growths on the heart valves, the endocardial lining of a heart chamber, or the epithelium of a blood vessel. (See Degenerative changes in endocarditis.) Such growths may cover the valve surfaces, causing ulceration and necrosis. They may also extend to the chordae tendineae, leading to rupture and subsequent valvular insufficiency. Ultimately, they may embolize to the spleen, kidneys, central nervous system, and lungs.

form on fragile, wartlike vegetative growths on the heart valves, the endocardial lining of a heart chamber, or the epithelium of a blood vessel. (See Degenerative changes in endocarditis.) Such growths may cover the valve surfaces, causing ulceration and necrosis. They may also extend to the chordae tendineae, leading to rupture and subsequent valvular insufficiency. Ultimately, they may embolize to the spleen, kidneys, central nervous system, and lungs.

Most cases of endocarditis occur in patients who:

are I.V. drug abusers

have mitral valve prolapse (especially with a systolic murmur)

have prosthetic heart valves

have rheumatic heart disease.

Other predisposing conditions include:

coarctation of the aorta

tetralogy of Fallot

subaortic and valvular aortic stenosis

ventricular septal defects

pulmonary stenosis

Marfan’s syndrome

degenerative heart disease, especially calcific aortic stenosis

rarely, a syphilitic aortic valve.

However, some patients with endocarditis have no underlying heart disease.

Infecting organisms differ among these groups. In patients with native valve endocarditis who aren’t I.V. drug abusers, causative organisms usually include (in order of frequency) streptococci, especially Streptococcus viridans, staphylococci, or enterococci. Although other bacteria occasionally cause the disorder, fungal causes are rare in this group. The mitral valve is the most common valve involved, followed by the aortic valve.

In patients who are I.V. drug abusers, Staphylococcus aureus is the most common infecting organism. Less common causes of the disorder are streptococci, enterococci, gram-negative bacilli, or fungi. The tricuspid valve is the most common valve involved, followed by the aortic valve and then the mitral valve.

In patients with prosthetic valve endocarditis, early cases (those that develop within 60 days of valve insertion) are usually caused by staphylococcal infection. However, gram-negative aerobic organisms, fungi, streptococci, enterococci, or diphtheroids may also cause the disorder. The course is usually sudden and severe and is associated with a high mortality rate. Late cases (occurring after 60 days) show signs and symptoms similar to native valve endocarditis.

Complications

Heart failure

Death

Aortic root abscess

Myocardial abscesses

Pericarditis

Cardiac arrhythmia

Meningitis

Cerebral emboli

Brain abscesses

Septic pulmonary infarcts

Arthritis

Glomerulonephritis

Acute renal failure

Assessment findings

The patient may report a predisposing condition and complain of nonspecific signs and symptoms, such as weakness, fatigue, weight

loss, anorexia, arthralgia, night sweats, and an intermittent fever that may recur for weeks.

Inspection may reveal petechiae of the skin (especially common on the upper anterior trunk) and the buccal, pharyngeal, or conjunctival mucosa, and splinter hemorrhages under the nails.

Rarely, you may see Osler’s nodes (tender, raised, subcutaneous lesions on the fingers or toes), Roth’s spots (hemorrhagic areas with white centers on the retina), and Janeway lesions (purplish macules on the palms or soles).

Clubbing of the fingers may be present in patients with longstanding disease.

Auscultation may reveal a murmur in most patients, except those with early acute endocarditis and I.V. drug abusers with tricuspid valve infection. The murmur is usually loud and regurgitant, which is typical of the underlying rheumatic or congenital heart disease. A murmur that changes suddenly or a new murmur that develops in the presence of fever is a classic sign of endocarditis.

Percussion and palpation may reveal splenomegaly in longstanding disease. In patients who have developed left-sided heart failure, your assessment may reveal dyspnea, tachycardia, and bibasilar crackles.

In 12% to 35% of patients with subacute endocarditis, embolization from vegetating lesions or diseased valve tissue may produce typical characteristics of splenic, renal, cerebral, or pulmonary infarction, or peripheral vascular occlusion:

– Splenic infarction causes pain in the left upper quadrant, radiating to the left shoulder, and abdominal rigidity.

– Renal infarction causes hematuria, pyuria, flank pain, and decreased urine output.

– Cerebral infarction causes hemiparesis, aphasia, and other neurologic deficits.

– Pulmonary infarction causes cough, pleuritic pain, pleural friction rub, dyspnea, and hemoptysis. These signs and symptoms are most common in patients with right-sided endocarditis, which typically occurs among I.V. drug abusers and after cardiac surgery.

– Peripheral vascular occlusion causes numbness and tingling in an arm, leg, finger, or toe, or signs of impending peripheral gangrene.

Diagnostic test results

Three or more blood cultures during a 24- to 48-hour period identify the causative organism in up to 90% of patients. The remaining

10% may have negative blood cultures, possibly suggesting fungal or difficult-to-diagnose infections such as Haemophilus parainfluenzae.

Other abnormal but nonspecific laboratory results include:

– normal or elevated white blood cell count and differential

– abnormal histiocytes (macrophages)

– normocytic, normochromic anemia (in patients with subacute infective endocarditis)

– elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and serum creatinine level

– positive serum rheumatoid factor in about half of patients with endocarditis after the disease is present for 6 weeks

– proteinuria and microscopic hematuria.

Echocardiography may identify valvular damage in most patients with native valve disease.

An electrocardiogram reading may show atrial fibrillation and other arrhythmias that accompany valvular disease.

Treatment

The goal of treatment is to eradicate all infecting organisms from the vegetation. Therapy should start promptly and continue over 4 to 6 weeks. Selection of an anti-infective drug is based on the infecting organism and sensitivity studies. Although blood cultures are negative in 10% to 20% of the subacute cases, the practitioner may want to determine the probable infecting organism.

Supportive treatment includes bed rest, aspirin for fever and aches, and sufficient fluid intake. Severe valvular damage, especially aortic insufficiency or infection of a cardiac prosthesis, may require corrective surgery if refractory heart failure develops or if an infected prosthetic valve must be replaced.

Nursing interventions

Stress the importance of bed rest. Assist the patient with bathing if necessary. Provide a bedside commode because using a commode puts less stress on the heart than using a bedpan. Offer the patient diversionary, physically undemanding activities.

To reduce anxiety, allow the patient to express his concerns about the effects of activity restrictions on his responsibilities and routines. Reassure him that the restrictions are temporary.

Before giving an antibiotic, obtain a patient history of allergies. Administer the prescribed antibiotic on time to maintain a consistent drug level in the blood.

Observe the venipuncture site for signs of infiltration or inflammation, a complication of long-term I.V. administration. To reduce the risk of this complication, rotate venous access sites.

Assess cardiovascular status frequently, and watch for signs and symptoms of left-sided heart failure, such as dyspnea, hypotension, tachycardia, tachypnea, crackles, and weight gain. Check for changes in cardiac rhythm or conduction.

Administer oxygen and evaluate arterial blood gas levels, as needed, to ensure adequate oxygenation.

Monitor the patient’s renal status (including blood urea nitrogen levels, creatinine clearance, and urine output) to check for signs of renal emboli and drug toxicity.

Make sure the susceptible patient understands the need for a prophylactic antibiotic before, during, and after dental work, childbirth, and genitourinary, GI, or gynecologic procedures. (See Teaching the patient with endocarditis.)

DISCHARGE TEACHING

TEACHING THE PATIENT WITH ENDOCARDITIS

TEACHING THE PATIENT WITH ENDOCARDITIS

Teach the patient about the anti-infective medication that he’ll continue to take. Stress the importance of taking the medication and restricting activity for as long as recommended.

Tell the patient to watch for and report signs of embolization and to watch closely for fever, anorexia, and other signs of relapse that could occur about 2 weeks after treatment stops.

Discuss the importance of completing the full course of antibiotics, even if he’s feeling better. Make sure susceptible patients understand the need for prophylactic antibiotics before, during, and after dental work, childbirth, and genitourinary, GI, or gynecologic procedures.

Teach the patient to brush his teeth with a soft toothbrush and rinse his mouth thoroughly. Tell him to avoid flossing his teeth and using irrigation devices.

Teach the patient how to recognize symptoms of endocarditis. Tell him to notify the practitioner immediately if such symptoms occur.

RED FLAG

RED FLAGWatch for signs and symptoms of embolization (hematuria, pleuritic chest pain, left upper quadrant pain, or paresis), a common occurrence during the first 3 months of treatment. Tell the patient to watch for and report these signs and symptoms, which may indicate impending peripheral vascular occlusion or splenic, renal, cerebral, or pulmonary infarction.

MYOCARDITIS

Myocarditis—a focal or diffuse inflammation of the myocardium—is typically uncomplicated and self-limiting. It may be acute or chronic and can occur at any age. In many patients, myocarditis fails to produce specific cardiovascular symptoms or electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormalities. Recovery usually is spontaneous and without residual defects.

Occasionally, myocarditis becomes serious and induces myofibril degeneration, right- and left-sided heart failure with cardiomegaly, and arrhythmias.

Pathophysiology

Damage to the myocardium occurs when an infectious organism triggers an autoimmune, cellular, and humoral reaction. The resulting inflammation may lead to hypertrophy, fibrosis, and inflammatory changes of the myocardium and conduction system. The heart muscle weakens and contractility is reduced. The heart muscle becomes flabby and dilated, and pinpoint hemorrhages may develop.

Causes of myocarditis include:

bacterial infections, such as diphtheria, tuberculosis, typhoid fever, tetanus, and staphylococcal, pneumococcal, and gonococcal infections

fungal infections, including candidiasis and aspergillosis

helminthic infections such as trichinosis

hypersensitive immune reactions, including acute rheumatic fever and postcardiotomy syndrome

parasitic infections, especially South American trypanosomiasis (Chagas’ disease) in infants and immunosuppressed adults; also toxoplasmosis

radiation therapy; large doses of radiation to the chest in treating lung or breast cancer

toxins, such as lead, chemicals, and cocaine, and alcoholism

viral infections (most common cause in the United States and western Europe), such as coxsackievirus A and B strains and, possibly, poliomyelitis, influenza, Epstein-Barr virus, human immunodeficiency virus, cytomegalovirus, measles, mumps, rubeola, rubella, and adenoviruses and echoviruses.

Complications

Assessment findings

The history commonly reveals a recent upper respiratory tract infection with fever, viral pharyngitis, or tonsillitis.

The patient may complain of nonspecific signs and symptoms, such as fatigue, dyspnea, palpitations, persistent tachycardia, and persistent fever, all of which reflect the accompanying systemic infection.

Occasionally, the patient may complain of a mild, continuous pressure or soreness in the chest. This pain is unlike the recurring, stress-related pain of angina pectoris.

Auscultation usually reveals S3 and S4 gallops, a muffled S1, possibly a murmur of mitral insufficiency (from papillary muscle dysfunction) and, if the patient has pericarditis, a pericardial friction rub.

If the patient has left-sided heart failure, you may notice pulmonary congestion, dyspnea, and resting or exertional tachycardia disproportionate to the degree of fever.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree