Inflammatory Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

RODNEY P. BENSLEY Jr and MARC L. SCHERMERHORN

Presentation

A 67-year-old man presents to the emergency department with complaints of abdominal pain. He reports intermittent sharp pain over the past several months that has become increasingly more intense in character over the past several days. The pain is centrally located with radiation to his midback. He denies alleviating or exacerbating characteristics. He also reports occasional low-grade fevers and a 10-pound weight loss over the past few months. He smokes heavily and has marginally controlled hypertension. He does have a family history of abdominal aortic aneurysms in his mother. On physical examination, he is afebrile, hemodynamically stable, and in moderate discomfort. His blood pressure is equal bilaterally, and pulses are fully palpable in all extremities. His abdomen is moderately tender in the periumbilical region without peritoneal signs. He has mild costovertebral angle tenderness.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for this clinical presentation is broad. The initial focus should be on potentially life-threatening conditions. In addition to the obvious vascular conditions, such as a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) or acute aortic dissection, other intra-abdominal conditions, such as mesenteric ischemia, intestinal volvulus, or a perforated viscus, need to be considered. Other conditions that are not immediately life threatening include neoplastic causes, pyelonephritis, nephrolithiasis, and ureterolithiasis. An inflammatory AAA is realistically very low on the differential. Inflammatory AAAs constitute 3% to 10% of all AAAs.

Discussion

This patient’s presentation requires a high index of suspicion and an aggressive diagnostic workup to rule out a potentially life-threatening diagnosis. In addition to timely laboratory studies, the current speed and detail of spiral computed tomography (CT) scanners make an intravenous contrast scan the imaging modality of choice. An intravenous CT scan can rule out an immediately life-threatening aortic condition. In addition to evaluating the vasculature, the CT scan can reveal any other intra-abdominal pathology that may be causing this patient’s symptoms. Magnetic resonance arteriography (MRA) is superior in diagnosing periaortic inflammation; however, its availability and the time required to obtain the images favor obtaining a CT scan at most institutions.

Workup

Laboratory Tests

Laboratory testing should be broad and include a complete blood count (CBC), basic metabolic panel, and liver function tests. Other tests that may be helpful include a coagulation profile, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein, and a urinalysis. This patient’s CBC is normal. His blood urea nitrogen is 34 mg/dL and creatinine is 1.2 mg/dL. His ESR is elevated at 101 seconds.

CT Scan

This patient’s CT scan demonstrates a 4.8 × 4.2-cm infrarenal AAA with significant fat stranding and wall thickening of the anterior and lateral aortic wall at the inferior portion of the AAA. The posterior wall of the aorta is relatively spared. There is mural thrombus but no evidence of aortic sac hemorrhage or extravasation. The ureters were of normal caliber and uninvolved. There were no other intra-abdominal abnormalities (Fig. 1). Note the inflammatory rind involving the anterior and lateral wall of the AAA. The posterior wall is spared.

FIGURE 1 CT scan demonstrating an infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm with an inflammatory rind involving the anterior and lateral walls of the aneurysm. Note that the posterior wall is spared.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Diagnosis

Inflammatory Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

The leading diagnosis in this patient is an inflammatory AAA. Patients with inflammatory AAAs frequently present with abdominal and back pain, an elevated ESR denoting a generalized inflammatory state, and imaging revealing a thickened aortic wall with inflammation of surrounding structures, such as the retroperitoneum, kidney and ureter, inferior vena cava, and duodenum. The ureters are involved in approximately 25% of cases. Weight loss is often present as well. Aneurysm development is multifactorial in nature with both a genetic predisposition and environmental factors contributing to aneurysmal degeneration of the aorta.

Inflammatory AAAs were first described in 1972. At the time, they were thought to be an entirely separate entity from noninflammatory AAAs; however, current understanding favors an inflammatory process similar to typical aneurysms, but with an advanced degree of inflammation.

Treatment

The decision to treat inflammatory AAAs should be based on the same criteria used to treat patients with degenerative-type aneurysms. The estimated rupture risk, operative risk, and life expectancy will all influence the decision to intervene. Concerning aortic characteristics, such as periaortic edema, pain, and involvement of surrounding structures, may prompt a more aggressive management strategy. Many inflammatory aneurysms are repaired urgently or emergently due to the inability to rule out acute expansion and imminent rupture.

This patient’s CT scan and laboratory values indicate the presence of an inflammatory aneurysm without involvement of the ureters and secondary hydronephrosis. Although the aneurysm does not appear to be leaking at this time, the progressive nature of his abdominal pain is of concern. If all other potential sources of his pain can be ruled out, it is reasonable to recommend an urgent repair of his inflammatory aneurysm. The operative approach to patients with inflammatory AAAs should have two primary objectives: (1) to effectively replace the aneurysm with a prosthetic conduit and (2) to manage the secondary fibrotic complications if present. In this patient, there are no fibrotic complications present.

Surgical Approach

Prior to the introduction of endovascular AAA repair, open AAA repair was the only feasible approach to aneurysm replacement. Open repair of inflammatory AAAs is technically demanding. Repair of inflammatory AAAs has been shown to have significantly increased operating room time and requirement of blood product transfusion as compared to open repair of noninflammatory AAAs. A retroperitoneal approach is recommended due to the extensive inflammation that often affects the anterior and lateral surfaces of the aorta. This approach attempts to minimize dissection through the surrounding dense fibrotic tissue. The limitations of this approach include the limited accessibility of the right ureter, right iliac artery, and duodenum. The dense fibrotic tissue may provide a good substance to the aortic wall to hold sutures; however, dehiscence of the anastomosis is a concern, and reinforcement of the anastomosis with Teflon pledgets or polytetrafluoroethylene strips can be performed. Early reports of open repair of inflammatory AAAs showed increased perioperative mortality and complications, but more contemporary series have demonstrated that the perioperative mortality and complications are comparable to open repair of noninflammatory AAAs. In situations where acute expansion or impending rupture is suspected, an anterior approach may also be employed, but the retroperitoneal approach is quite feasible for urgent AAA repair as well.

The endovascular approach to inflammatory AAAs is appealing as it obviates the need for difficult dissection through fibrotic tissue and the pitfalls of performing a hand-sewn anastomosis to tissues of questionable quality. There have been numerous reports in the literature describing successful endovascular approaches to these aneurysms. As mentioned, it obviates the need for difficult dissection through fibrotic tissue and its accompanying risk of injury to surrounding structures. There have been reports that the endovascular approach is not associated with the degree of resolution of the inflammation that is seen with open repair. In a study by Stone et al., there was a decrease in the inflammatory rind by 51% after endovascular repair of inflammatory AAAs.

Ureteral obstruction is seen in approximately 25% of these patients and is due to the periaortic and retroperitoneal fibrosis. If there is significant hydronephrosis and deterioration of renal function, ureteral stents can be placed perioperatively to relieve the acute obstruction and to act as a guide to identifying the ureters intraoperatively. After repair of the inflammatory AAA, the fibrosis usually resolves along with the ureteral obstruction. If symptoms of obstruction persist, additional intervention may be necessary, such as ureterolysis, ureteral stent placement, or lysis of intra-abdominal adhesions. Appropriate follow-up is necessary to prevent long-term complications of end-organ damage, such as renal atrophy from chronic ureteral obstruction.

This patient was not a candidate for an endovascular approach secondary to anatomic considerations nor did he have any ureteral involvement based on CT scan or deterioration of renal function based on laboratory values, so ureteral stents were not placed. Therefore, a left retroperitoneal approach was utilized to expose the aneurysm. Minimal dissection was needed around the ureters and duodenum. Proximal and distal control were obtained, and an infrarenal cross-clamp was applied. Healthy aortic tissue was isolated to perform the anastomosis. Teflon pledgets were used to reinforce the anastomosis. The remainder of the procedure followed standard aortic surgery techniques.

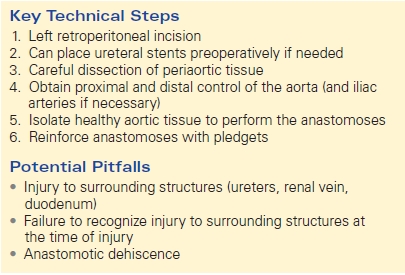

Pitfalls of open repair of inflammatory AAAs included injury to surrounding structures such as the ureter, kidney, and duodenum. The dense fibrotic tissue that is often present makes dissection difficult and challenging. The aortic tissue used in the anastomosis can be of questionable quality so reinforcement with pledgets can be performed to decrease the risk of dehiscence. Persistent ureteral obstruction and periureteral inflammation can increase the likelihood of injury to the ureter during dissection. Placement of ureteral stents can serve as a guide in identifying the ureter during dissection (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Open Repair of Inflammatory AAA