DEFINITION

Infectious endocarditis (IE) is defined as infection of the vascular endocardium typically involving heart valves and congenital heart defects. Other arterial vascular beds may also be involved. The hallmark of the infection is known as vegetation, which may vary in size ranging from millimeter to centimeters, consisting mainly of a fibrin-platelet matrix infiltrated by abundant microorganisms. The disease may occur in an acute or fulminating form or in a chronic insidious form known as subacute bacterial endocarditis.

Acute IE is associated with a severe rapid and destructive process often caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Both normal and damaged valves may be affected by the organism. In the subacute form, viridian streptococcus is often the cause of the endocarditis. It usually affects previously damaged heart valves and certain congenital defects.

It is estimated that nearly 10,000 to 15,000 new cases of IE are diagnosed yearly in the United States (

1). This number continues to increase. Men appear to be more prone than women to develop IE (

2). The incidence of IE is greater in urban areas (11.6 cases vs. five cases per 100,000 person years in semiurban regions) (

3,

4). A follow-up study from the same semiurban region spanning three decades showed that the incidence has remained remarkably unchanged (

5). Older individuals (older than 60 years) seem to be more susceptible to the disease (

6).

A normal cardiac valve is usually resistant to endocarditis. However, under certain circumstances, such as when a virulent organism is involved or when the host is immunocompromised, as in an injection drug user, a normal valve may become infected. In most cases of IE, underlying valvular or congenital heart defects are present. Blood-flow turbulence induced by lesions such as valvular insufficiency causes further trauma to the endothelial surface, promoting the aggregation and deposition of platelet-fibrin matrix over the damaged surface. These aggregates can become secondarily infected via bacteremia originating from various sources, resulting in typical vegetations containing abundant microorganisms.

USUAL CAUSES

Nearly 50% of individuals who develop native valve endocarditis (NVE) appear to have some predisposing structural cardiac abnormalities. These include rheumatic heart disease, mainly mitral valve involvement, congenital defects, mainly ventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus, bicuspid aortic valve, and coarctation of the aorta. Other conditions, such as mitral valve prolapse with mitral regurgitation, degenerative valvular disease, and hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, are also considered risk factors for IE. Patients with prior prosthetic cardiac valves are considered at high risk for IE (PVE). Injection drug users are particularly susceptible to both right- and left-sided endocarditis. Nosocomial sources of infection from medical intervention, such as the use of intravenous catheters, pacemakers, dialysis shunts, and prosthetic vascular grafts, should not be overlooked as contributors to risk of IE in susceptible individuals. Subjects with prior risk of IE are

considered to be at increased risk of recurrence of the infection.

Almost any microorganism can cause IE, but the three most common bacteria incriminated include Streptococcus viridans, Staphylococcus aureus, and Enterococcus faecalis. S. viridans, an α-hemolytic streptococcus, is responsible for about half the cases. These bacteria are normal commensals of the pharynx and upper respiratory tract. Dental procedures such as cleaning or extraction, bronchoscopy, or tonsillectomy result in infection in susceptible individuals.

S. aureus can cause both acute and subacute endocarditis. It is the commonest offending microorganism among injection drug users (IDUs). Based on the International Collaboration on Endocarditis-Prospective Cohort Study, variations appear to be present in the risk characteristics of patients in whom

S. aureus endocarditis developed in the different countries (

7). Thus cases in the United States were more likely to be hemodialysis dependent, diabetic, and likely to have intravascular devices, pacemakers, or central venous catheters. A nosocomial mode of infection seemed more likely than the community-acquired source.

Coagulase-negative staphylococci (S. epidermidis), fungi (Histoplasma, Candida, Aspergillus), and Brucella species are organisms that commonly cause infection in patients with prosthetic valves, IDUs, and alcoholic persons. Because E. faecalis is found in the perineal region and feces, genitourinary procedures, pelvic surgery, pelvic infections, and prostatic disease in older men are predisposing factors for this infection.

Streptococcus bovis in the bowel often causes IE in the elderly. A striking relationship has been noted between this organism and colonic abnormalities, including adenoma and carcinoma.

Coxiella burnetii is a rickettsia that is widespread in both domestic and farm animals. It spreads to humans through aerosols, dust, and unpasteurized milk. HACEK an acronym for a group of fastidious organisms [Haemophilus parainfluenzae, Haemophilus aphrophilus, Actinobacillus (Haemophilus) actinomycetemcomitans, Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella species, and Kingella species may account for 5% to 10% of cases of IE].

Other causative bacteria include

Streptococcus pyogenes, Neisseria, and

Pseudomonas. The blood culture may occasionally be negative even after 7 days, usually termed culture-negative endocarditis. Prior antibiotic use or involvement of fastidious bacteria or fungi may account for this phenomenon (

Table 20.1).

Acute Endocarditis

The onset usually dates to a preceding suppurative infection or to intravenous drug abuse. Persistent fever, new heart murmurs, vasculitis, hemorrhagic petechiae, embolic phenomena, metastatic abscesses, and development of heart failure are suggestive of acute endocarditis. S. aureus is usually implicated in acute endocarditis.

Subacute Endocarditis

The onset of illness is insidious, and the date of onset is usually unclear. Patients are initially seen with systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, anorexia, weight loss, rigors, arthralgia, symptoms of heart failure, or embolism. Heart failure results from destruction of valves or rupture of chordae, and in these cases, the onset may be more fulminant. Embolic phenomena include stroke, pulseless limbs, pulmonary infarctions, or renal infarctions. Thus a combination of heart murmur, anemia, hematuria, and renal failure should raise the suspicion of subacute endocarditis.

Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis

Two modes of onset occur in PVE. The first has an early onset, developing soon after surgery, and is caused by bacterial contamination of the prosthesis at the time of surgery or during the perioperative period due to septicemia. The second has a late onset and is caused by infection of the valve as a result of persistent bacteremia. Infection of the valve ring occurs in both types; vegetations can interfere with valve function, and myocardial abscesses can interfere with the cardiac conduction system.

Clinical Features of Infectious Endocarditis

Symptoms

The symptoms and signs and their frequencies are shown in

Table 20.2. Nonspecific symptoms of inflammation, including intermittent fever, malaise, anorexia, weight loss, and rigors, may occur. Fever may be absent in moribund or immunocompromised individuals. Some patients also complain of myalgia and arthralgia. Endocarditis must always be suspected in a patient with a heart murmur and fever. Progressive cardiac failure is another presenting feature, and the onset of heart failure can be dramatic when destruction of a valve occurs. Emboli from vegetations can result in a pulseless limb, stroke, renal infarction, or pulmonary infarction. Loin pain and arthralgia may occur because of immune complex deposition. Low lumbar back pain is a fairly typical complaint, although this must be elicited by gentle pressure on the lower back. The cause of the pain is unclear.

Signs

Cardiac: a change in the character of an existing murmur or the development of a new systolic murmur must raise the suspicion of infective endocarditis. In some instances, the only finding may be a “trivial” aortic regurgitation. In right-sided endocarditis, murmurs are not usually present.

Vascular lesions: Such lesions include petechiae, Roth spots, Janeway lesions, subungual splinter hemorrhages, and Osler nodes (

Fig. 20.1). Petechial or mucosal hemorrhages are caused by vasculitis and are typically small and red with a pale center. They are seen on the conjunctiva or pharyngeal mucosa. Those seen on the retina are called Roth spots. Janeway lesions are flat, small, erythematous macules that are not tender and are seen mainly on the hypothenar and thenar eminences. These lesions blanch with pressure. Osler nodes are painful, tender, hard, subcutaneous swellings that occur in the palms, soles, toes, and fingers.

Clubbing of fingers: Clubbing of fingers typically occurs in persons with subacute bacterial endocarditis. This is, however, a late manifestation and is rarely seen nowadays.

Splenomegaly: Splenomegaly is a feature of subacute endocarditis, and usually the spleen is mildly enlarged.

Renal manifestations: Microscopic hematuria is almost always present. Frank hematuria is suggestive of renal infarction caused by emboli. Acute glomerulonephritis and renal abscesses are other manifestations.

Arthritis: Arthritis of major joints has been reported frequently.

Embolic phenomena: Stroke can be caused by emboli to the middle cerebral artery and its branches. Vegetations can embolize and result in infarction of a limb, lungs, or myocardium.

Mycotic aneurysms: These can occur anywhere on the vascular tree; when cerebral vessels are affected, cerebral hemorrhage may be found.

Extracranial mycotic aneurysms: These are usually asymptomatic until they rupture or leak. These can also occur in intrathoracic or intraabdominal vessels.

HELPFUL TESTS

Laboratory tests: Typically, affected patients have normocytic normochromic anemia. Usually, an increase in neutrophils with mild thrombocytopenia is found. Markers of inflammation, including the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, are increased, and hemolysis due to paraprosthetic leaks may occur.

Liver-function tests: Mild derangement of liver-function test results may be found, particularly an increased alkaline phosphatase level.

Immunoglobulin: An increase in serum immunoglobulin levels is often present.

Complement: Both total complement and C3 complement levels are decreased as a result of immune complex formation.

Urine: Microscopic hematuria is an almost constant phenomenon, and proteinuria may occur.

Blood cultures: Blood cultures are positive in about 90% of cases, permitting

identification of the suspected pathogen and determination of susceptibility of the organism to antimicrobial agents. At least three separate sets of cultures, 1 hour apart from separate venipuncture samplings, should be taken. Each set equals one aerobic bottle and one anaerobic bottle. Special cultures may be required for HACEK organisms and

Bartonella,

Legionella,

Brucella, and

Histoplasma species. The administration of antibiotics before obtaining blood cultures may reduce the yield of isolated pathogens by 35% or 40%. Polymerase chain reaction testing on blood is useful when the suspected pathogens are

Tropheryma whippleii or

Bartonella species.

Serologic tests: serologic tests may be required when uncommon organisms,

including

Coxiella, Chlamydia, Candida,

Bartonella, and

Brucella species, are suspected.

Chest radiograph: Chest radiography is useful for documenting pulmonary septic emboli in right-sided endocarditis or for confirming evidence of cardiac failure.

Electrocardiogram: Electrocardiography may show defects in cardiac conduction or, in rare cases, myocardial infarction caused by emboli.

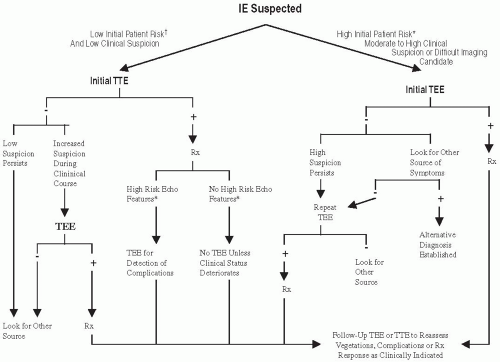

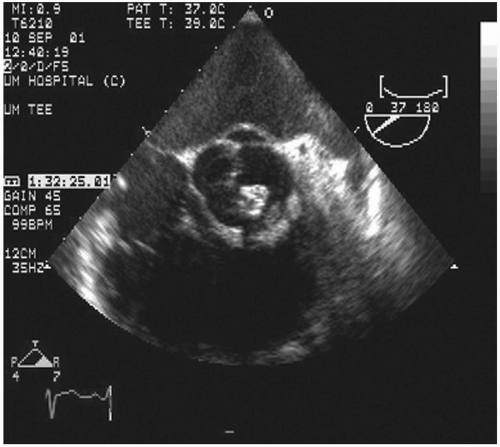

Echocardiography:

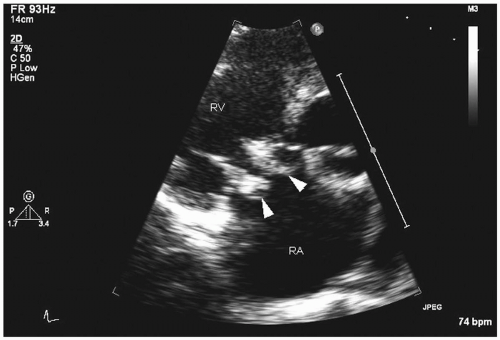

Fig. 20.2 and

Table 20.3A show the recommendations for the use of echocardiography in the diagnosis of IE.

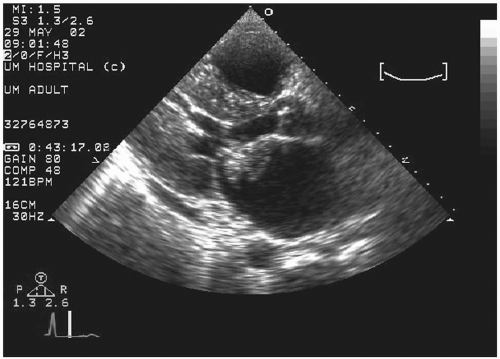

Transthoracic echocardiography: four major echocardiographic features of infective endocarditis are typical: vegetations, abscesses, new prosthetic valve dehiscence, or new regurgitation, which must be interpreted in combination with other clinical features (

8) (

Fig. 20.3). Transthoracic echocardiography cannot exclude the diagnosis of infective endocarditis, and in a fifth of the cases, vegetations may not be detected because of obesity, chest-wall abnormalities, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. For vegetations, this procedure has good specificity (98%), but sensitivity is only 60%

(

9,

10,

11). The procedure is useful in detecting vegetations larger than 2 mm in diameter, particularly on right-sided valves that are close to the anterior portion of the chest. (

Fig. 20.4) (

12). It is not useful in excluding prosthetic valve endocarditis, perforation of leaflets, fistulae, or periannular abscess (

11,

13); therefore a negative study result in a suspected case does not rule out endocarditis. The other limitation is that a positive study result does not rule out major complications.

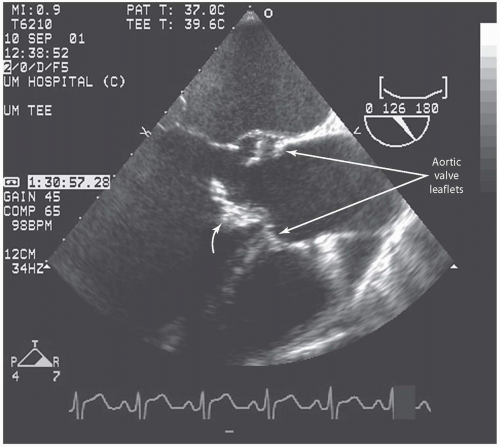

Transesophageal echocardiography: This procedure is the investigation of choice and more accurately identifies infective endocarditis (

Figs. 20.5 and

20.6). Transesophageal echocardiography is particularly suitable for investigating PVE. The sensitivity is 86% to 94%, and specificity is 88% to 100%. Abscesses of the aortic root, a serious complication, are reliably excluded only by this procedure. It has a specificity of 94%, and sensitivity varies from 76% to 100% for perivalvular infection because the esophageal transducer allows examination of the root of the aorta and basal part of the

ventricular septum, where most such complications occur. However, the technique is not 100% sensitive for other infection, and in such situations, the diagnosis may have to be made on clinical grounds. False-negative findings result from prior embolization of vegetations, small size of vegetations, or inadequate views to detect small abscesses.

Another limitation is that prosthetic valve shadows may not allow complete visualization; therefore multiple views and planes must be studied to decrease the number of false-negative findings. Also, a combination of transthoracic and transesophageal techniques may have to be used to obtain accurate images; when both studies yield negative results, the negative predictive value approaches 95% The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) committee recommends (

14) that when clinical suspicion of infective endocarditis is high and the transesophageal study result is negative, a repeated study should be considered within 7 to 10 days to demonstrate previously undetected vegetations or abscesses. After a course of therapy, vegetations may

persist in nearly 60% of the patients, and this does not correlate with subsequent complications; however, any increase in the size of the vegetations with therapy heralds late complications, despite absence of persistent bacteremia or clinical features of ongoing infection (

15,

16).