Infected Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

MARTYN KNOWLES and J. GREGORY MODRALL

Presentation

A 76-year-old male cattle farmer with a history of hypertension, diabetes, and coronary artery disease presented to the emergency room with a 12-day history of abdominal pain, malaise, recurrent fevers to 102°F, and chills. Vital signs included a temperature of 101.3°F, heart rate of 107 bpm, and blood pressure of 138/78 mm Hg. He is tender to palpation in the epigastrium, and has palpable pedal pulses bilaterally. Laboratory studies revealed a white blood cell count of 17 × 109/L and a serum creatinine of 1.57 mg/dL. A noncontrast computed tomogram of the abdomen was obtained (Fig. 1).

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) with constitutional symptoms includes an infected AAA, aortic pseudoaneurysm (noninfected), penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer, aortic dissection, and noninfected degenerative AAA. Particular attention should be paid to an AAA that develops or changes quickly, exhibits saccular morphology, produces constitutional symptoms, or exhibits stranding around the aneurysm on computed tomography (CT) scan. Any aneurysm associated with these findings on history or CT scan should be assumed to be infected.

Workup

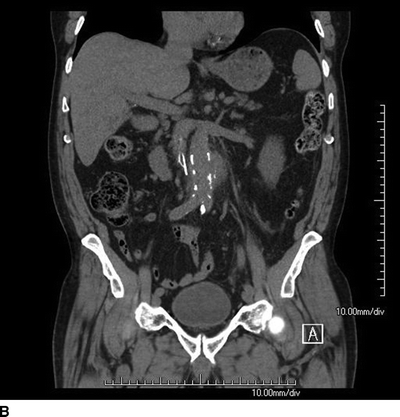

Appropriate imaging should include a CT angiogram with appropriate thin cuts (<3 mm), but a noncontrast CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained in this case due to the elevated serum creatinine. The CT scan revealed a 5-cm saccular infrarenal AAA near the inferior mesenteric artery with periaortic stranding (Fig. 1). Even without contrast, one can make out the calcification of the aortic wall with the presence of loss of distinct margins of the aorta, periaortic thickening, and stranding. Laboratory evaluation with blood cultures demonstrated Salmonella growth in the blood.

FIGURE 1 Axial (A) and coronal (B) cut of a CT scan showing a saccular infrarenal AAA with periaortic stranding.

Discussion

Infected AAA refers to several pathologic conditions that lead to the presence of infection in an AAA. Examples of infected AAAs include mycotic aneurysms due to endocarditis, microbial arteritis (from bacteremia) with aneurysm formation, infection of a preexisting AAA, and posttraumatic infected false aneurysms of the aorta. In most infected AAAs, the infection causes degeneration of the aorta to produce an aneurysm. Fewer than 5% of infected AAAs result from infection of a preexisting AAA. The most common site for an infected AAA is the infrarenal aorta (70%), but infected AAAs occasionally occur in the suprarenal or thoracic aorta.

Diagnosis of an infected AAA usually involves a high index of suspicion and imaging studies suggestive of the diagnosis. Clinical scenarios that should arouse suspicion for an infected AAA include the presence of positive blood cultures in a patient with a known AAA, identification of a new AAA after a septic episode, and concurrent AAA and lumbar vertebral erosions. An antecedent history of a septic episode may be identified in approximately 61% of cases but is not a requirement for the diagnosis. The most common presenting symptoms of an infected AAA are abdominal pain (92%), fever (77%), leukocytosis (69%), positive blood cultures (69%), palpable abdominal mass (46%), and rupture (31%).

Radiographic imaging should include both a contrast-enhanced CT scan and an arteriogram. CT findings suggestive of an infected AAA include the presence of a saccular aneurysm, evidence of partial aortic disruption or frank rupture, contiguous inflammatory changes, fluid collections, or air adjacent to an AAA. The vast majority of infected AAAs are saccular aneurysms, although infection of an existing aneurysm typically occurs in a fusiform aneurysm because most AAAs have a fusiform morphology. Arteriography often aids in the diagnosis by demonstrating saccular aneurysm morphology and facilitates operative planning. A high-quality CT arteriogram (CTA) with three-dimensional reconstruction may obviate the need for arteriography.

Treatment

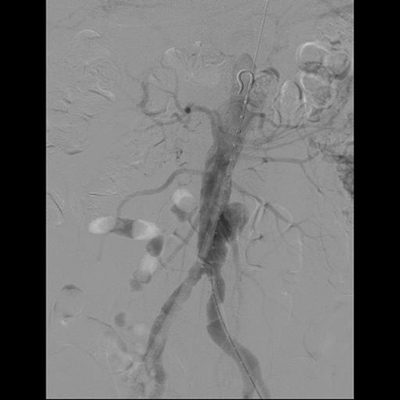

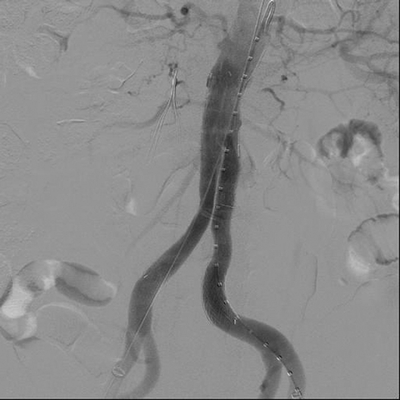

The presence of an infected AAA obligates urgent repair. The risk of rupture is greater with the findings of symptoms, CT evidence of surrounding stranding, saccular nature of the AAA, or rapid growth. In addition to systemic antibiotics, the mainstay of treatment is aneurysm resection and debridement of the retroperitoneum. The options for aortic reconstruction include aortic ligation with extra-anatomic bypass, in situ placement of rifampin-soaked Dacron graft, cryopreserved arterial allograft, or femoropopliteal vein (FPV). In the case above, the patient developed chest pain at admission and was found to have an ST elevation inferior wall myocardial infarction and was taken urgently for percutaneous coronary intervention. The patient was taken subsequently for an aortogram (Fig. 2) and temporary repair with endovascular aortic aneurysm repair (EVAR) (Fig. 3) under local anesthesia to mitigate the risk of AAA rupture. The patient was then placed on culture-directed antibiotic coverage.

FIGURE 2 Aortogram showing a saccular infrarenal aneurysm.

FIGURE 3 Infected AAA treated with temporary exclusion using a Gore Excluder endograft (W.L. Gore and associates, Flagstaff, AZ).

Options for Surgical Repair

The mainstay of treatment of infected AAAs is excision of all grossly infected aortic and retroperitoneal tissue. It is not necessary to debride to microscopically uninfected tissue, but generous debridement is thought to decrease the risk of recurrent infection of the aorta or aortic reconstruction. Reconstruction of the aorta may be accomplished with either extra-anatomic bypass or in situ interposition grafting. The clinical outcomes for each of these options are summarized in the Table 1 below. Extra-anatomic bypass with an axillobifemoral bypass, followed by removal of the infected aneurysm and aortic stump ligation, is the most commonly performed reconstruction. However, this option carries a significant risk of stump blowout (approximately 20%), reinfection of the graft in 3% to 15%, and a mortality rate between 10% and 25%. This option is most appropriate for patients who are deemed high risk for in situ reconstruction. Unfortunately, the patency of these extra-anatomic repairs is relatively poor (as low as 45% at 3 years).

TABLE 1. Infected Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm