This chapter reviews the pathophysiology and medical management in relation to the comprehensive physical therapy management of individuals with chronic primary cardiovascular and pulmonary pathology. Exercise testing and training are major components of the comprehensive physical therapy management of individuals with chronic primary cardiovascular and pulmonary conditions, and this topic is presented in detail in Chapter 24. Because the heart and lungs are interdependent and function as a single unit, primary lung or heart disease must be considered with respect to the other organ and in the context of oxygen transport overall.1,2 Despite a plethora of research and numerous official position statements and clinical practice guidelines, the definition and diagnoses of chronic heart disease and chronic lung disease and their management remain inconsistent in practice.3 Although there is consensus regarding the effectiveness of both cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation,4 this inconsistent practice is associated with the underuse, overuse, and misuse of therapies regardless of their established effectiveness. The principles of the physical therapy management of people with various chronic primary cardiovascular and pulmonary conditions are presented rather than treatment prescriptions, which cannot be discussed without consideration of a specific patient (see Case Study Guide to accompany the text on-line). In this context, the general goals of the long-term management of people with each condition are presented, followed by the essential monitoring required and the primary interventions for maximizing cardiovascular and pulmonary function and oxygen transport. The selection of interventions for any given patient is based on the physiological hierarchy. The most physiological interventions are exploited first, followed by less physiological interventions and those whose effectiveness is less well documented (see Chapter 17). A template of care is shown in Table 31-1. Although there are many commonalities of physical therapy management across patients, only a detailed knowledge of each specific patient, in terms of his or her underlying pathologies and other factors, will lead to the optimal management plan and treatment prescriptions. Table 31-1 Angina pectoris refers to pain resulting from reduced blood flow to the myocardium. Even though it is usually elicited during exercise, angina may be triggered by stress or in severe cases may occur at rest. Atherosclerosis of one or more of the coronary arteries is the principal cause. Coronary vasospasm is a less common cause of angina. The pathophysiology of angina is described in detail in Chapter 5. A history of angina necessitates further examination to establish the severity of the coronary artery occlusion. Individuals with manifestations of heart disease are categorized according to their limitation during physical activity based on the New York Heart Association (NYHA) Functional Classification (Table 31-2). Table 31-2 New York Heart Association Functional Classification If angina is severe and refractory to medical management, the patient is scheduled for coronary bypass surgery (Chapters 29 and 30) to restore normal coronary blood flow. The acute and long-term management of the surgical cardiac patient is presented in Chapter 30. In less severe cases, angina is managed conservatively with medications (e.g., sublingual nitroglycerin, nitroglycerin patch, education, and physical therapy). After the patient’s condition has stabilized, a graded exercise tolerance test may be conducted under supervision in a cardiac stress testing facility where 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring can be performed. The exercise intensity at which the patient exhibits angina (i.e., the anginal threshold) can be quantified and serve as the basis for the prescription of physical activity and exercise. The goals of long-term management of the patient with angina include the following: Patients with angina are at risk of having an infarction; therefore vigilance and stringent monitoring are necessary to detect angina or frank myocardial infarction. These patients are potentially hemodynamically unstable; thus their hemodynamic responses before, during, and after treatment, particularly aerobic and strengthening exercises, should be monitored and recorded. Minimally, heart rate, blood pressure, and rate-pressure product should be recorded, along with the patient’s subjective responses to treatment. Heavy lifting, static exercise, straining, the Valsalva maneuver, and heavy, repetitive upper-extremity work are avoided during physical activity and exercise. These activities are associated with a disproportionate hemodynamic response. Physical activity and aerobic exercise are prescribed at a target heart rate or perceived exertion ranges that are below the anginal threshold based on a graded exercise tolerance test (see Chapters 19 and 24). Peak exercise tests in patients with cardiac dysfunction that may elicit angina or ST-segment changes are performed in a cardiac stress testing laboratory, usually under the supervision of a cardiologist unless in a specialized facility where physical therapists perform such testing. The body position in which aerobic exercise is performed is important in patients with heart disease. Positions of recumbency increase the volume of fluid shifted from the periphery to the central circulation. This increases venous return and the work of the heart. Therefore upright body positions have long been known to minimize cardiac work during exercise in these patients and during rest after exercise.5,6 Sexual dysfunction is common in individuals with systemic atherosclerosis owing in part to underlying pathology (dyslipidemia, vascular insufficiency, and diabetes), medication, and the psychological impact of heart disease.7 In terms of energy demands, those of sexual activity are comparable to those of other daily activities (e.g., walking 1 mile on the level). Optimizing health in general with diet and exercise can contribute to regression of atherosclerosis and improved peripheral circulation. Breathing control, body positioning, and energy conservation strategies such as exercising at a high energy time of day may also help minimize symptoms. Also, patients should be advised to avoid sexual activity within an hour of eating, and even then not to consume a heavy meal. The patient’s ECG will be important for determining the parameters of exercise, the level of monitoring required, and education. Dysrhythmias are described in Chapter 4, and basic ECG reading is presented in Chapter 12. Ventricular dysrhythmias can be lethal. Occasional premature ventricular contractions must be monitored to ensure that their frequency remains low and that coupling does not occur. Atrial fibrillation is considered a relatively serious dysrhythmia. It is associated with a high incidence of coronary disease, stroke, and overall mortality.8 Medication or a pacemaker may be necessary. Central sleep-disordered breathing is highly prevalent in individuals with left ventricular dysfunction and is associated with abnormal cardiac autonomic control and increased dysrhythmias.9 Although sleep-disordered breathing may not be related to the severity of hemodynamic dysfunction, loss of recuperative sleep will affect functional capacity as well as capacity and motivation to participate in an exercise program and be physically active. Health-related quality of life reported by individuals with chronic heart failure is associated with function and exercise capacity, not with ejection fraction.10 Health-related quality of life should be an outcome measure for all individuals managed for heart failure because it provides important supplemental information that is independent of physiological indices of cardiac function and the NYHA classification of function (see Table 31-2). Nonpharmacological approaches to the management of individuals with heart failure are an essential component to the overall management of the condition.11 These measures are incorporated into an individualized program of health behavior change, and include the following: Risk factor modification is a major goal. A marker of inflammation such as C-reactive protein along with appropriate lipid testing findings may be a more discriminating risk factor than lipid profiling alone.12 Refining the risk factor definition on the basis of C-reactive protein level will help target management (e.g., indicate necessity for intensified exercise programs, weight loss, and smoking cessation). After discharge from the hospital, many patients who have had a myocardial infarction see a physical therapist either privately or through a cardiac rehabilitation program. Patients may remain on a supervised rehabilitation program, including an exercise program, for 6 to 12 months in a specialized center (see Chapter 24). Depression is a common symptom reported by individuals with coronary artery disease and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Individuals with depressive symptoms are more likely to exhibit myocardial ischemia during mental stress testing and during activities of daily living.13 Myocardial ischemia induced by mental stress may be a mechanism by which depression increases the risk of morbidity and mortality in individuals with coronary artery disease. Although aggressive type A individuals are thought to have an increased incidence of heart disease compared with passive type B personalities, anger and hostility have been identified as the toxic negative emotions most implicated in morbidity and mortality related to heart disease.14 A graded exercise tolerance test is conducted before the patient leaves the hospital or when he or she is enrolled in an exercise program. The time between the exercise test and the exercise prescription and implementation of the exercise program should be minimal. Peak (formerly referred to as maximal) exercise tests are conducted in the presence of a cardiologist (unless in a specialized facility where physical therapists may do such testing) and provide the optimal basis for an exercise prescription. Submaximal exercise tests can be conducted by the physical therapist and can provide the basis for an exercise program; however, the prescription should be conservative compared with the prescription based on the peak exercise test. The principles and practice of exercise testing are described in Chapters 19, 24, and 25. Such testing is both an art and an exacting science and should be carried out in a rigidly standardized manner to ensure the test results are maximally valid, reliable, and useful. The goals of long-term management of the patient with myocardial infarction include the following: Peak exercise tests in cardiac patients that may elicit angina or ST-segment changes are performed in a cardiac stress testing laboratory under the supervision of a cardiologist. The parameters of the exercise prescription are set based on a peak exercise test. Intensity is set within a heart rate, oxygen consumption, and exertion range (e.g., 70% to 85% of the anginal threshold) (see Chapter 19). As with patients with angina, the body position in which aerobic exercise is performed by patients with myocardial infarction is important. Positions of recumbency increase the volume of fluid shifted from the periphery to the central circulation. This increases venous return and the work of the heart. Therefore upright body positions are selected for these patients to minimize cardiac work during exercise and during rest after exercise.5,6,15 Clinically, patients with valve disease may demonstrate exertional dyspnea, excessive fatigue, palpitations, fluid retention, and orthopnea. These signs and symptoms are often relieved when exertion is discontinued. Aerobic exercise, however, has been shown to reduce the symptoms of prolapsed valve.16 Anxiety has been reported to decrease general well-being. If effectively managed, however, reduced anxiety can improve or reduce chest pain, fatigue, and dizziness. The goals of long-term management of the patient with valvular heart disease include the following: Physical therapists are involved in the management of patients with valve defects with regard to both the medical aspects, either as a primary or secondary problem, and surgical aspects. After surgery these patients progress well; the principles of their management are presented in Chapter 30. With respect to the medical management of valve defects, the goal is to optimize oxygen transport in the patient for whom surgery is not indicated either because the defect is not sufficiently severe or because the patient cannot or refuses to undergo surgery. Although the mechanical defect cannot be improved, oxygen transport may be improved in some patients with judicious exercise prescription. The parameters of the exercise prescription are usually moderate in that inappropriate exercise doses can further disrupt the inappropriate balance between oxygen demand and supply and thus further exacerbate symptoms. In addition, there is the potential for further valvular dysfunction if the myocardium is mechanically strained. 1. Does the defect preclude treatment? 2. Does the defect require that treatment be modified? If so, how? 3. What special precautions should be taken? 4. What signs and symptoms would indicate the patient is distressed? 5. What parameters should be monitored? 6. Is the patient taking medications as prescribed? How might these medications alter the patient’s response to treatment? 7. Is there any evidence of heart failure? If so, what will the effects of exercise be? 8. If there is no evidence of heart failure at rest, what is the chance that insufficiency will develop with exercise? The body position in which aerobic exercise is performed is important in patients with heart disease. Positions of recumbency increase the volume of fluid shifted from the periphery to the central circulation. This increases venous return and the work of the heart. Therefore upright body positions are selected for these patients to minimize cardiac work during exercise and during rest after exercise.5,6 Peripheral vascular disease refers to diseases of the arteries and the veins. Peripheral arterial disease results primarily from atherosclerosis and occlusion of the peripheral arteries (e.g., thoracic aorta, femoral artery, and popliteal artery).17 The diagnosis may be overlooked until serious limb ischemia is evident.18 Diabetes mellitus, which can result in microangiopathy and autonomic polyneuropathy, is another important cause of PVD in the lower extremities. Venous disease results in phlebitis, venous stasis, and thromboembolus and leads to valvular incompetence of the veins of the legs. Individuals with PVD secondary to diabetes mellitus have accelerated atherosclerosis compared with age-matched individuals without diabetes. Diabetes affects the macrocirculation and microcirculation; thus wounds must be prevented, particularly in the lower legs and feet, and managed aggressively should they occur. These individuals may be at risk for lower extremity lesions because of autonomic neuropathy and angiopathy. To restore insulin sensitivity and promote weight loss, activity levels must be significantly increased, and a formal exercise program instituted. Weight-bearing activities are safe for individuals with poor sensation in the feet and do not increase the risk of reulceration.19 It should be assumed that individuals with peripheral arterial disease have coronary and cerebral arterial disease necessitating aggressive risk factor management to reduce the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and death.20 Primary interventions include smoking cessation; treatment of hypertension, glucose intolerance, and diabetes; and management of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. The primary interventions for maximizing cardiovascular and pulmonary function and oxygen transport in patients with PVD secondary to atherosclerosis include some combination of education, aerobic exercises, strengthening exercises, relaxation, activity pacing, and energy conservation. Exercise, in particular walking, is an important component of management to ameliorate symptoms and improve functional capacity and quality of life.18,21 Pharmacotherapy may help relieve symptoms in the short term, whereas exercise benefits are likely to be long term in terms of addressing systemic atherosclerosis. An ergonomic assessment of both work and home environments may be indicated to minimize myocardial strain. Individuals with PVD may underestimate their increased risk of cardiovascular disease22

Individuals with Chronic Primary Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Dysfunction

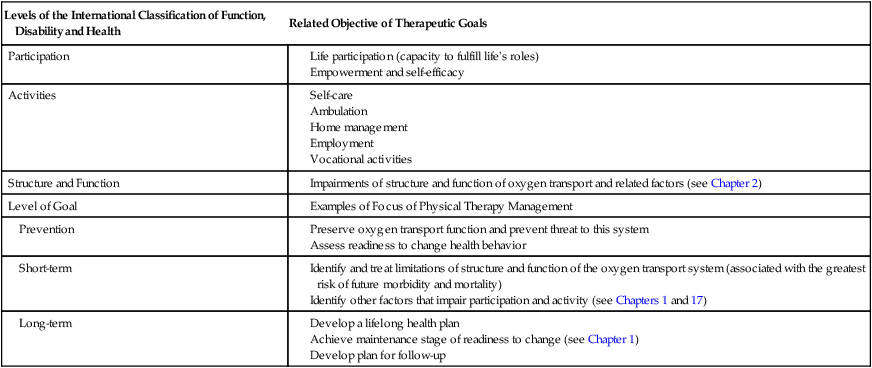

Levels of the International Classification of Function, Disability and Health

Related Objective of Therapeutic Goals

Participation

Activities

Structure and Function

Level of Goal

Prevention

Short-term

Long-term

Individuals with Primary Cardiovascular Disease

Angina

Pathophysiology and Medical Management

Classification

Characteristics

I

No symptoms and no limitation in ordinary physical activity.

II

Mild symptoms and slight limitation during ordinary physical activity.

III

Marked limitation in activity as a result of symptoms, even during less-than-ordinary activity. Comfortable only at rest.

IV

Severe limitations. Experiences symptoms even while at rest.

Principles of Physical Therapy Management

Maximize the patient’s quality of life, general health, and well-being through maximizing physiological reserve capacity

Maximize the patient’s quality of life, general health, and well-being through maximizing physiological reserve capacity

Educate regarding heart disease, self-management, nutrition, weight control, smoking reduction and cessation, anger and stress management, disease prevention, risk factors, medications and their use, physical activity, and exercise

Educate regarding heart disease, self-management, nutrition, weight control, smoking reduction and cessation, anger and stress management, disease prevention, risk factors, medications and their use, physical activity, and exercise

Maximize aerobic capacity and efficiency of oxygen transport of all steps in the pathway

Maximize aerobic capacity and efficiency of oxygen transport of all steps in the pathway

Optimize physical endurance and exercise capacity

Optimize physical endurance and exercise capacity

Optimize general muscle strength and thereby peripheral oxygen extraction

Optimize general muscle strength and thereby peripheral oxygen extraction

Design comprehensive lifelong health and rehabilitation programs with the patient

Design comprehensive lifelong health and rehabilitation programs with the patient

Myocardial Infarction

Pathophysiology and Medical Management

Promote adherence to the recommendations

Promote adherence to the recommendations

Avoid added sodium (salt and preservatives)

Avoid added sodium (salt and preservatives)

Maintain optimal blood cholesterol and triglyceride levels

Maintain optimal blood cholesterol and triglyceride levels

Maintain normal blood pressure

Maintain normal blood pressure

Restrict fluid in the presence of congestive heart failure

Restrict fluid in the presence of congestive heart failure

Restrict alcohol use to a moderate amount, if any

Restrict alcohol use to a moderate amount, if any

Principles of Physical Therapy Management

Maximize the patient’s quality of life, general health, capacity to return to work, and well-being through maximizing physiological reserve capacity

Maximize the patient’s quality of life, general health, capacity to return to work, and well-being through maximizing physiological reserve capacity

Educate regarding myocardial infarction, self-management, nutrition, weight control, smoking reduction and cessation, relaxation and stress management, risk factors, disease prevention, medications, lifestyle, activities of daily living, and avoidance of static exercise, straining, and the Valsalva maneuver

Educate regarding myocardial infarction, self-management, nutrition, weight control, smoking reduction and cessation, relaxation and stress management, risk factors, disease prevention, medications, lifestyle, activities of daily living, and avoidance of static exercise, straining, and the Valsalva maneuver

Maximize aerobic capacity and efficiency of oxygen transport

Maximize aerobic capacity and efficiency of oxygen transport

Optimize physical endurance and exercise capacity

Optimize physical endurance and exercise capacity

Optimize general muscle strength and thereby peripheral oxygen extraction

Optimize general muscle strength and thereby peripheral oxygen extraction

Design comprehensive lifelong health and rehabilitation programs with the patient

Design comprehensive lifelong health and rehabilitation programs with the patient

Valve Disease

Pathophysiology and Medical Management

Principles of Physical Therapy Management

Maximize the patient’s quality of life, general health, and well-being through maximizing physiological reserve capacity

Maximize the patient’s quality of life, general health, and well-being through maximizing physiological reserve capacity

Educate regarding cardiac valvular disease, self-management, nutrition, weight control, smoking reduction and cessation, relaxation and stress management, cardiac risk factors, disease prevention, medications, lifestyle, activities of daily living, and avoidance of static exercise, straining, and the Valsalva maneuver

Educate regarding cardiac valvular disease, self-management, nutrition, weight control, smoking reduction and cessation, relaxation and stress management, cardiac risk factors, disease prevention, medications, lifestyle, activities of daily living, and avoidance of static exercise, straining, and the Valsalva maneuver

Maximize aerobic capacity and efficiency of oxygen transport

Maximize aerobic capacity and efficiency of oxygen transport

Optimize physical endurance and exercise capacity

Optimize physical endurance and exercise capacity

Optimize general muscle strength and thereby peripheral oxygen extraction

Optimize general muscle strength and thereby peripheral oxygen extraction

Design comprehensive lifelong health and rehabilitation programs with the patient

Design comprehensive lifelong health and rehabilitation programs with the patient

Peripheral Vascular Disease

Pathophysiology and Medical Management

Principles of Physical Therapy Management

Maximize the patient’s quality of life, general health, and well-being through maximizing physiological reserve capacity

Maximize the patient’s quality of life, general health, and well-being through maximizing physiological reserve capacity

Educate regarding atherosclerosis, heart disease, and other sequelae, self-management, nutrition, weight control, smoking reduction and cessation, risk factors, disease prevention, medications, lifestyle, activities of daily living, and avoidance of static exercise, straining, and the Valsalva maneuver

Educate regarding atherosclerosis, heart disease, and other sequelae, self-management, nutrition, weight control, smoking reduction and cessation, risk factors, disease prevention, medications, lifestyle, activities of daily living, and avoidance of static exercise, straining, and the Valsalva maneuver

If impaired peripheral perfusion of the limbs is present, educate regarding self-assessment of the skin; sock type, care, and cleanliness; shoe fitting; and wound care if indicated

If impaired peripheral perfusion of the limbs is present, educate regarding self-assessment of the skin; sock type, care, and cleanliness; shoe fitting; and wound care if indicated

Maximize aerobic capacity and efficiency of oxygen transport

Maximize aerobic capacity and efficiency of oxygen transport

Optimize the work of the heart

Optimize the work of the heart

Optimize physical endurance and exercise capacity

Optimize physical endurance and exercise capacity

Optimize general muscle strength and thereby peripheral oxygen extraction

Optimize general muscle strength and thereby peripheral oxygen extraction

Design comprehensive lifelong health and rehabilitation programs with the patient

Design comprehensive lifelong health and rehabilitation programs with the patient

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Individuals with Chronic Primary Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Dysfunction