1 Individualized Assessment for Percutaneous or Surgical Revascularization

Introduction

Introduction

The revascularization of patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) has progressed exponentially since Andreas Grüntzig performed the first balloon angioplasty in 1977.1 These developments, which have been fueled by new technology, have blurred the boundary between what is considered exclusively surgical disease and what can be treated percutaneously. Consequently there is a greater need than ever to tailor revascularization appropriately, taking into consideration a patient’s comorbidities, coronary anatomy, and personal preferences. This chapter first explores the increasing requirement for a more individualized assessment of patients undergoing revascularization; then it reviews the risk models currently available to assist in this stratification process. Finally, risk stratification from the individual patient’s perspective is discussed.

The Need for Individualized Patient Assessment

The Need for Individualized Patient Assessment

Patient Comorbidities

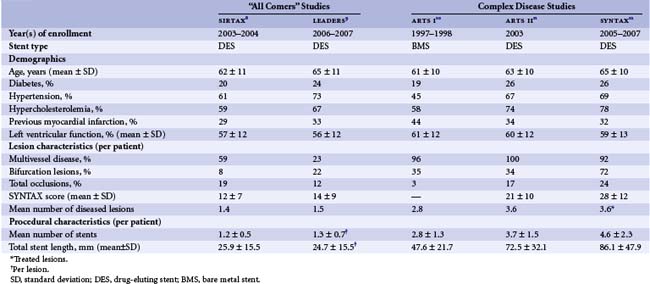

The demographics of patients in need of revascularization who present to tertiary care services are changing. This has largely been the consequence of increased longevity of the general population, a lower threshold to investigate patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of obstructive coronary disease, and increased resources, making revascularization by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) more accessible. Owing to their generally older age, patients in need of revascularization are now more likely to have comorbidities, such as diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.2,3 These factors are all implicated in accelerating the progression of CAD; consequently patients are more likely to present with more extensive disease. The Arterial Revascularization Therapies Studies (ARTS) Parts I and II were separated by a period of 5 years and, although both studies had the same inclusion criteria, patients in ARTS II had a significantly greater incidence of risk factors and overall increased disease complexity (Table 1-1).4

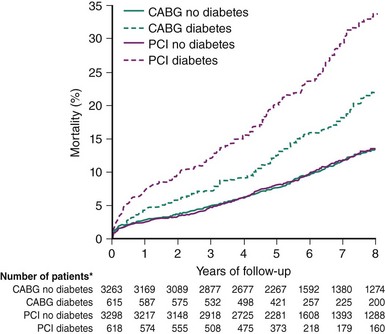

Comorbidities must be taken into consideration in assessing patients for revascularization, as these have the potential to significantly influence outcomes; moreover, the impact of treatment may depend on the underlying revascularization strategy selected. Of note, Legrand et al.5 demonstrated that patient age was a significant independent predictor of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) in patients enrolled in the ARTS I and II studies who were treated with CABG but not in those who received PCI. In a collaborative patient-level analysis of 10 randomized trials of patients with multivessel disease (MVD) treated with PCI using bare metal stents (BMS) and CABG, Hlatky et al.6 demonstrated comparable 5-year mortality rates among both the PCI and CABG treatment groups in patients without diabetes. Importantly, among those with diabetes, mortality was significantly higher in patients treated with PCI even after multivariate adjustment (Figure 1-1). The clear importance of patient comorbidities is highlighted by their central presence in the risk models now used to assist in decision making. This topic is discussed at greater length further on in this chapter.

Technological Advances

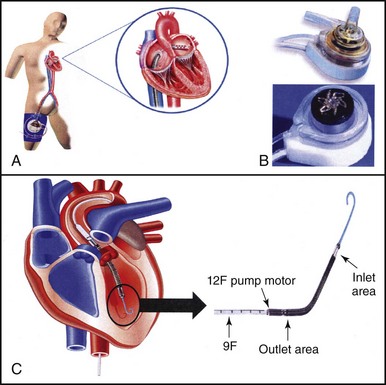

The introduction in 2002 of the drug-eluting stent (DES) revolutionized the practice of interventional cardiology, primarily owing to the dramatic reduction in rates of repeat revascularization resulting from its use.7 The impressive results seen with the use of the DES promptly led to an expansion in the indications for PCI, such that bifurcation lesions, chronic total occlusions, and MVD were increasingly treated with PCI. Previously, these lesion subsets had been deemed more appropriate for surgical revascularization. Evidence of this expansion can be seen in the changing baseline lesion characteristics of patients enrolled in “all comers” PCI studies such as SIRTAX (sirolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents for coronary revascularization trial),8 LEADERS (Limus Eluted from A Durable versus ERodable Stent coating study)9 and studies of complex (triple-vessel disease [3VD], and/or left main [LM]) CAD such as ARTS I,10 ARTS II,11 and the SYNTAX study (SYNergy between percutaneous coronary intervention with TAXus and cardiac surgery) (Table 1-1).12 Further evidence in support of this change come, from assessments of “real world” clinical practice, which indicate that approximately one-third of patients with complex disease are now treated with PCI.13 Coupled with this expanding use of PCI, driven largely through the beneficial effects of DES, the new lower-profile balloons and guidewires are among other advances; these also include new adjunctive pharmacological therapies and the increasing availability of percutaneous extracorporeal circulatory support (Figure 1-2).14,15 From a technical point of view, therefore, the majority of coronary lesions can now be addressed with PCI; however, this approach may not always be appropriate, necessitating the careful selection of individual patients.

Clinical Trial Results

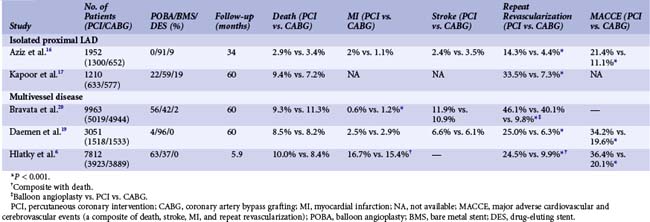

Randomized trials comparing CABG and PCI have centered on two major patient groups: those with isolated lesions of the proximal left anterior descending artery and those with complex disease, namely 3VD and/or LM disease. Taking the results of these studies at face value and irrespective of which patient group has been assessed, results at short- and long-term follow-up suggest that there are no differences in the hard clinical outcomes of death and myocardial infarction (MI) between patients treated with PCI or CABG (Table 1-2).6,16–20 Undisputedly CABG has been associated with a clear, consistent, and significant reduction in rates of repeat revascularization. Importantly, all of these studies have several notable limitations that restrict the ability to extrapolate their results to routine clinical practice. This, consequently, reinforces the need to assess patients individually before a revascularization therapy is selected.

TABLE 1-2 A Summary of Metanalyses Reporting Long-Term Outcomes in Patients with Isolated Proximal LAD Disease or Multi-Vessel Disease Randomized to Percutaneous or Surgical Revascularization

The SYNTAX Trial

This study aimed to supply evidence to support the already established, but not evidence-based practice of performing PCI in patients with complex disease13; it also sought to identify which patients should be treated only with CABG. The study design attempted to address the limitations of the earlier trials described above; in doing so, it was anticipated that the results would be more relevant to clinicians’ everyday practice. Specifically, it was intended to do the following:

TABLE 1-3 The SYNTAX Score Algorithm38*

| Adverse lesion characteristics |

* The angiographic components of the SYNTAX score. Each component is assigned a specific weight according to its contribution to procedural risk. The characteristics above are scored for each lesion with a greater than 50% diameter stenosis; these are added together to provide the total SYNTAX score. Full definitions of all variables are published38,39 and available online (www.syntaxscore.com).

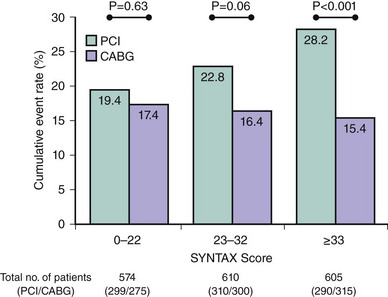

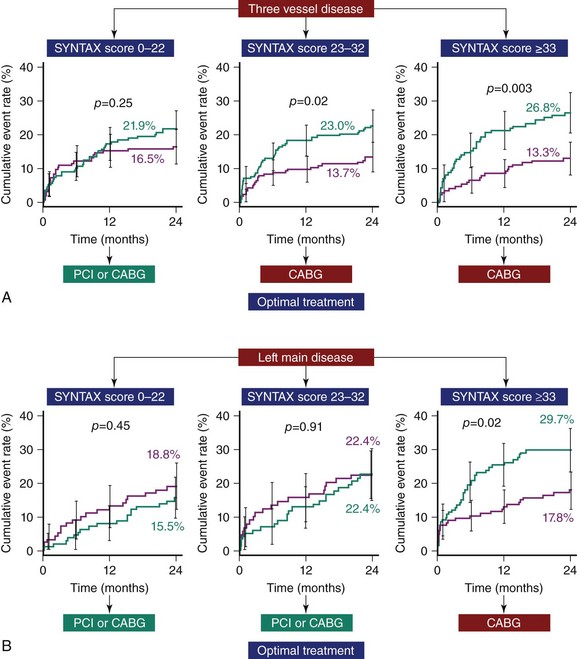

Overall the study failed to meet the prespecified primary endpoint of noninferiority in terms of 12-month major adverse cardio- and cerebrovascular events (MACCE), a composite of death, stroke, MI, and repeat revascularization (17.8% vs. 12.4%, P = 0.002). This was driven by significantly lower rates of repeat revascularization with CABG (13.5% vs. 5.9%, P < 0.0001). Moreover, consistent with prior studies of MVD, there were no significant differences in the overall safety endpoints of death, MI, or death/stroke/MI out to 12 months of follow-up. Results at the 2-year follow-up, which are considered hypothesis-generating in view of the failure to reach the primary endpoint, are somewhat similar to earlier results, with comparable rates of death (PCI 6.2% vs. CABG 4.9%, P = 0.24) and the composite of death/stroke and MI (10.8% vs. 9.6%, P = 0.44), while significantly higher rates of repeat revascularization (17.4% vs. 8.6%, P < 0.001) and overall MACCE (23.4% vs. 16.3%, P < 0.001) were seen with PCI.25 As indicated earlier, the analysis of all patients irrespective of disease severity does not provide adequate information for clinicians, who daily see patients with wide variations in CAD complexity. To address this limitation of earlier studies, patient outcomes in the SYNTAX study were stratified according to terciles of the SXscore. As shown in Figure 1-3, clinical outcomes between patients treated with PCI and CABG were similar in those with low SXscores, trended in favor of CABG in the intermediate group, and were significantly lower in the CABG group among patients with high SXscores. The intermediate group was further subdivided into a 3VD cohort, where outcomes were lower with CABG, and into an LM cohort, where outcomes were comparable between PCI and CABG (Figure 1-4).26,27 These results reiterate the importance of assessing patients when a revascularization strategy is being selected. The SYNTAX study was able to identify those patients in whom either PCI or CABG was appropriate and, perhaps more importantly, the group of patients in whom CABG was the optimal treatment. Considering the distribution of CAD in the SYNTAX study, overall one-third of patients with 3VD/LM disease were deemed to have CAD that could be treated safely and effectively with PCI or CABG; in the remaining two-thirds, CABG remained the standard of care. Although these results were consistent with what was already practiced,13 validation of the SXscore importantly facilitates a more objective assessment of patients, as discussed in the following pages.

Figure 1-3 Two-year rates of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (a composite of death, stroke, myocardial infarction, and repeat revascularization) among the 1,800 patients randomized to PCI or CABG in the SYNTAX study, stratified according to SYNTAX score. Of note, clinical outcomes were comparable between PCI and CABG in those with an SXscore of 0 to 22, trended in favor of CABG in those with an SXscore of 23 to 32, and were significantly lower with CABG in those with an SXscore ≥ 33.25

Figure 1-4 The evidence supporting the use of the SYNTAX score as a tool to assist in revascularization decisions. A. In patients with three-vessel disease, the rate of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE, a composite of death, stroke, myocardial infarction, and repeat revascularization) at 2-year follow-up was comparable only between patients treated with PCI and CABG for SYNTAX scores of 0 to 22; for all other SYNTAX scores, outcomes were significantly better following CABG.26 B. In patients with left main disease, clinical outcomes were comparable between patients treated by PCI or CABG for all SYNTAX scores, apart from those above 32, when outcomes were significantly better with CABG (CABG: purple line; PCI: green line).27

Individual Assessment—From a Physician’s Perspective

Individual Assessment—From a Physician’s Perspective

There is no disputing the need and potential benefit of selecting a revascularization strategy only after an individualized patient assessment or risk stratification. Risk stratification is performed routinely and subconsciously by physicians in everyday clinical practice and is in essence behind all clinical decisions that are made. Stratification of risk is vital in assessing patients for revascularization, as this treatment is considered appropriate only when “the expected benefits, in terms of survival or health outcomes (symptoms, functional status, and/or quality of life) exceed the expected negative consequences of the procedure.”28 The factors that have increased the importance of risk stratification in contemporary practice have already been discussed. The currently available methods of stratifying patients for risk are described in the following paragraphs.

Qualitative Versus Quantitative Risk Assessment

Quantitative risk stratification can be performed using a variety of risk models that incorporate clinical variables sourced from large patient databases.29–36 These risk models largely incorporate objective variables, thus ensuring adequate reproducibility of the score. However, models such as the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) lesion score37 or the SYNTAX score,38 which include angiographic variables, continue to have documented intra- and interobserver variability.39,40 In addition to their role in the risk stratification of individual patients, these quantitative risk models have increasing use in the wider context of overall healthcare. They can provide a vital measure of overall patient care and can help to identify future directions to further improve outcomes. Clinical governance and the increasing requirement to report clinical performance (and complications) publicly have also propelled the need to risk stratify patients, thereby allowing useful comparisons of performance to be made between clinicians (and institutions) and the standards dictated by regulatory authorities.41 In addition, the calculation of risk using accepted risk models can aid clinicians who are faced with an increasing need to justify their clinical decisions to peers, regulatory bodies, and patients. In comparison to the qualitative risk models, the use of a finite number of variables makes these model less sensitive and therefore less able to accurately predict risk in an individual, such that they are more effective in predicting risk for a population of patients with similar comorbidities. The number of variables included in the model must strike a balance between sufficient numbers to enable the calculation of a meaningful prediction of risk; however, the number must not be so excessive as to prevent the use of the model in routine practice. In addition, a minimal number of variables reduces the chances of colinearity between independent variables, which can result in the collection of redundant information34

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree