At the onset of wide complex tachycardia, beats with intermediate morphologies sometimes occur between the normally conducted beats and the wide complex tachycardia QRS. Intermediate beats could be true fusion; however, progressive aberrancy has been reported to mimic true fusion. To evaluate the incidence of progressive aberrancy, wide complex tachycardia tracings were collected in which an intermediate beat was noted at the onset. When the associated electrocardiographic findings were diagnosed as supraventricular tachycardia, the beat was identified as progressive aberrancy. When diagnosed as ventricular tachycardia, the intermediate beat was identified as true fusion. Electrocardiographic criteria were then identified from this cohort to identify the distinguishing features between progressive aberrancy and true fusion. Of 24 episodes of wide complex tachycardia, 17 (71%) were identified as true fusion and 7 (29%) as progressive aberrancy. The QRS duration of the intermediate and wide complex tachycardia beats were shorter with progressive aberrancy than with true fusion (109 ± 23 ms vs 131 ± 20 ms, p <0.023; and 139 ± 21 ms vs 177 ± 24 ms, p <0.001, respectively). In progressive aberrancy (n = 3), the PR interval of the intermediate beat was always greater than the PR interval of the normally conducted beat. In contrast, in true fusion (n = 11), the PR interval of the intermediate beat was always less than the PR interval of the normally conducted beat. Multiple intermediate beats were present in 4 of 7 cases of progressive aberrancy and in 0 of 17 cases of true fusion. In conclusion, true fusion is the most common explanation for intermediate beats, but progressive aberrancy occurs a significant proportion of the time (29%). The identified criteria will be helpful in differentiating ventricular tachycardia from supraventricular tachycardia with aberrancy as a cause of wide complex tachycardia.

The hallmark of a typical fusion beat is that it has a QRS complex that is intermediate between the normally conducted supraventricular beat and the ventricular focus. However, not all such intermediate beats might represent fusion beats. Progressive aberrancy is an electrocardiographic phenomenon that has been described to occur at the onset of rapid atrial pacing. Although it has been described clinically, it is not widely appreciated as a cause of apparent “fusion complexes.” In progressive aberrancy, the first beat of the tachycardia also has an intermediate morphology between the normally conducted QRS complex and the fully aberrant complex of the wide complex tachycardia. Progressive aberrancy has previously been shown to mimic fusion beats. It is unknown how often this occurs clinically and whether electrocardiographic features exist that allow one to distinguish true fusion from progressive aberrancy. Because this distinction could aid in the differentiation of ventricular tachycardia from supraventricular tachycardia, the present study was performed to address how often intermediate beats result from true fusion versus progressive aberrancy and how to best differentiate them.

Methods

The Northwestern University institutional review board approved the present study. An electrophysiology consultant (J.G.) prospectively collected clinical electrocardiographic tracings during which a wide complex tachycardia was noted, with the first beat demonstrating an intermediate complex between the wide complex tachycardia and the normally conducted supraventricular beats. A total of 24 tracings were obtained from 24-hour ambulatory Holter monitors (n = 6), stress tests (n = 2), and inpatient telemetry (n = 16) during a 5-year period. The diagnosis of ventricular tachycardia versus supraventricular tachycardia with aberrancy was made clinically according to other clinical features—other tracings, electrophysiologic testing, and/or a response to drugs. The definitive diagnosis was ventricular tachycardia or supraventricular tachycardia with aberrancy in all 24 cases. Using this diagnosis, the intermediate beat was diagnosed as either true fusion or progressive aberrancy.

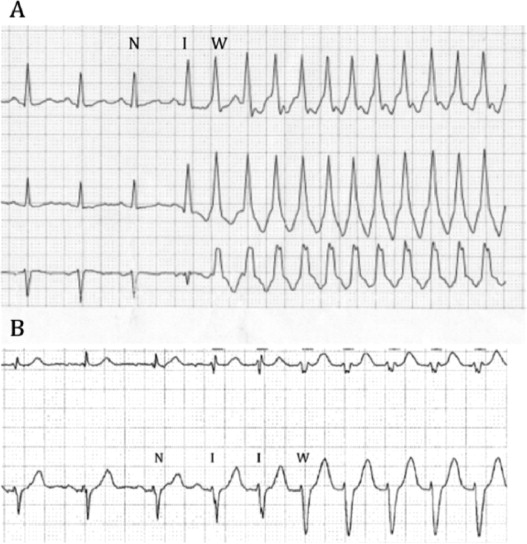

The following electrocardiographic features were identified as potential distinguishing features between true fusion and progressive aberrancy and were determined or measured on each tracing, when possible. The QRS durations of the preceding normally conducted beat, the intermediate beat, and the wide complex tachycardia beat were measured. When the P waves could be visualized, the PR interval of the normally conducted beats and the intermediate beat was measured. We hypothesized that true fusion would be associated with a shortening of the PR interval and progressive aberrancy with a lengthening of the PR interval. This was quantified as the ΔPR (the difference between the PR interval of the intermediate beat and the normally conducted beat; note, positive values indicate a longer PR interval for the intermediate beat). Because aberrant conduction at the onset of tachycardia typically appears when a short coupling interval follows a longer interval, the ratio of the coupling interval to the intermediate beat and the previous interval (see example in Figure 1 ) was calculated. If multiple beats were present with intermediate morphology, the number of intermediate beats was noted.

The data are presented as the mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t test. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 24 cases of a wide complex tachycardia with an intermediate beat were identified in 23 patients (1 patient had both progressive aberrancy and true fusion on separate occasions). Their mean age was 66 ± 15 years, and 16 were men. Seventeen tracings were ventricular tachycardia, leading to a diagnosis of true fusion for the intermediate beat. Seven tracings were supraventricular tachycardia with aberrancy, leading to a diagnosis of progressive aberrancy for the intermediate beat. Thus, progressive aberrancy accounted for 29% of the cases of intermediate beats in the present series. Figure 1 provides examples of true fusion and progressive aberrancy. The underlying rhythm was sinus in 17 cases, atrial fibrillation in 5, and atrial flutter in 2.

No significant difference was found in patient age between the 2 groups (73 ± 8 years for those with true fusion vs 63 ± 17 years for those with progressive aberrancy, p <0.10). Associated cardiac disease was more commonly noted in patients with true fusion (12 of 17, 71%) than in those with progressive aberrancy (3 of 7, 43%).

The QRS durations noted in the normally conducted beat, intermediate beat, and wide complex tachycardia beats in each group are listed in Table 1 . No significant difference was noted in the normally conducted QRS duration between the progressive aberrancy and true fusion groups. However, the QRS duration of the intermediate beats and wide complex tachycardia beats were significantly shorter in the progressive aberrancy group than in the true fusion group. For the intermediate beats, the QRS duration was 108.6 ± 22.7 ms and 131.2 ± 20.0 ms for the progressive aberrancy and true fusion groups, respectively (p = 0.024). For the wide complex tachycardia beats, the corresponding QRS durations were 138.6 ± 21.2 ms and 177.1 ± 24.4 ms (p <0.001).

| Variable | n | QRS Duration (ms) | Wide Complex Tachycardia Cycle Length (ms) | ΔPR (ms) | Coupling Interval Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normally Conducted Beat | Intermediate Beat | Wide Complex Beat | |||||

| Progressive aberrancy | 7 | 84 ± 17 | 109 ± 23 | 139 ± 21 | 418 ± 132 | 25 ± 7 | 0.67 ± 0.17 |

| True fusion | 17 | 103 ± 28 | 131 ± 20 | 177 ± 24 | 431 ± 168 | −34 ± 31 | 0.90 ± 0.25 |

| p Value | 0.11 | 0.023 | 0.001 | 0.84 | 0.009 | 0.04 | |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree