Although different guidelines on adult congenital heart disease (ACHD) care advocate for lifetime cardiac follow-up, a critical appraisal of the guideline implementation is lacking. We investigated the implementation of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association 2008 guidelines for ACHD follow-up by investigating the type of health care professional, care setting, and frequency of outpatient visits in young adults with CHD. Furthermore, correlates for care in line with the recommendations or untraceability were investigated. A cross-sectional observational study was conducted, including 306 patients with CHD who had a documented outpatient visit at pediatric cardiology before age 18 years. In all, 210 patients (68.6%) were in cardiac follow-up; 20 (6.5%) withdrew from follow-up and 76 (24.9%) were untraceable. Overall, 198 patients were followed up in tertiary care, 1/4 (n = 52) of which were seen at a formalized ACHD care program and 3/4 (n = 146) remained at pediatric cardiology. Of those followed in formalized ACHD and pediatric cardiology care, the recommended frequency was implemented in 94.2% and 89%, respectively (p = 0.412). No predictors for the implementation of the guidelines were identified. Risk factors for becoming untraceable were none or lower number of heart surgeries, health insurance issues, and nonwhite ethnicity. In conclusion, a significant number of adults continue to be cared for by pediatric cardiologists, indicating that transfer to adult-oriented care was not standard practice. Frequency of follow-up for most patients was in line with the ACC/AHA 2008 guidelines. A considerable proportion of young adults were untraceable in the system, which makes them vulnerable for discontinuation of care.

Although guidelines on the provision of adult congenital heart disease (ACHD) follow-up care were published about a decade ago, implementation of these recommendations in clinical practice has yet to be examined. Therefore, this cross-sectional study describes the implementation of American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) 2008 guidelines for ACHD care through the investigation of the type of professional, the setting, and the frequency at which outpatient visits are performed in young adults with CHD. Furthermore, this report explores the profile of patients who received care in line with the recommendations or who appeared untraceable in the health care system.

Methods

This observational study was conducted at a large freestanding pediatric hospital (Boston Children’s Hospital) in the United States that has an outpatient cardiology volume of >23,000 visits. There is an ACHD care clinic on-site and a transitioning liaison helping patients navigate from pediatric cardiology to ACHD care. Eligible patients were selected from the pediatric cardiology outpatient clinic list overviewing all visits performed from 2001 to 2005. Based on the following criteria, patients were selected: a confirmed diagnosis of CHD, born in 1987 (aged 23 years in 2010), at least 1 documented outpatient pediatric cardiology visit at the institution from 2001 to 2005 (<18 years), and living in the region of New England (United States) at the time of data collection (2012).

A clinical research form was completed after reviewing patient’s medical files. Information on sex, highest level of education, primary CHD diagnosis, number of previous cardiac interventions, and type of health insurance was collected based on chart review at the last outpatient visit. The ethnicity of patients was determined based on self-report. Based on the Zip code of the place of residence, the travel distance (miles) to the nearest ACHD center was calculated. Data collection and chart review were performed in 2012.

Furthermore, a 4-phase approach was used to determine the setting and frequency of the outpatient visits. During phase 1, the hospital’s cardiology database was checked to determine if patients were currently in follow-up at the institution. Subsequently, the Social Security Death Index was checked to exclude deceased patients. If data were missing or unavailable, and the mortality status remained undetermined, the last known cardiologist was contacted. Finally, if no additional information on follow-up could be provided by this cardiologist, the patient was contacted through mail or telephone using the patient’s last known contact details. The CHD diagnosis was determined based on chart review. The primary heart lesion was rank ordered using a modified CONgenital COR Vitia classification. The defect was anatomically defined as simple, moderate, or complex using Task Force 1. Patients were considered to be currently in follow-up if an outpatient visit could be documented using the aforementioned 4-phase protocol. Furthermore, patients were categorized as not being in cardiac follow-up if a complete cessation of cardiac care was confirmed. If at stage 4, the patient could not be contacted, then this patient was considered to be untraceable, and no further information on the cardiac follow-up care was collected. Detailed information on the setting and frequency of scheduled visits was derived. The setting of care was subdivided into 4 groups: care provided by (1) a pediatric cardiologist exclusively, (2) an ACHD cardiologist exclusively, (3) a general community cardiologist in collaboration with a specialized CHD team (i.e., shared care), or (4) a general community cardiologist solely. To assess the implementation of the ACC/AHA 2008 guidelines, the setting and frequency of visits was compared with the recommended setting of care and frequency of visits.

This study was approved by the Boston Children’s Hospital Center for Clinical Investigation and was performed in accordance with the 2002 Declaration of Helsinki. Data were analyzed using SPSS 20.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois). To explore the profile of patients receiving care at the recommended setting and frequency and patients found to be untraceable, 2 multivariable logistic regression models were analyzed (forced entry method). Assumptions of linearity, multicollinearity, and independence of errors were checked and found to be met. Results were reported as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. All statistical tests were 2 sided, and a p-value of 0.05 was used as a cut-off point for statistical significance.

Results

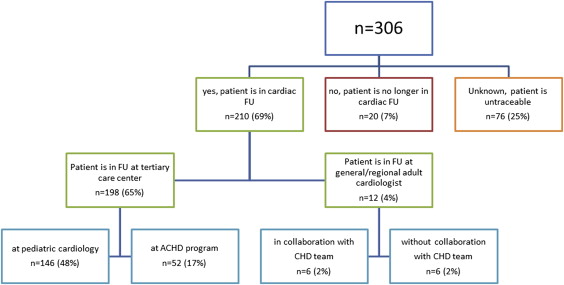

A total of 327 patients were eligible. However, 1 patient explicitly opted out of further inquiries. Twenty patients moved out of New England, leaving 306 patients (94%) included in data analysis. Demographic and clinical characteristics are provided in Table 1 . A total of 210 patients (68.6%) were in cardiac follow-up at the age of 23 years. However, 20 patients (7%) withdrew from follow-up. For 76 patients (25%), information on the setting or the frequency of follow-up could not be retrieved. In addition, direct contact with patient through last known phone or address was not possible. Therefore, these patients were considered to be untraceable. Within the group of patients who were in follow-up, the majority (n = 198, 65%) received cardiac care at tertiary care, whereas 12 patients (4%) were in follow-up with a non-CHD specialized community cardiologist. Although 52 patients (17%) followed in tertiary care were seen at an ACHD program, the majority (n = 146, 48%) still received pediatric cardiology care ( Figure 1 ).

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 180 (59%) |

| Female | 126 (41%) |

| Primary diagnosis | |

| Hypoplastic left-heart syndrome | 2 (1%) |

| Univentricular heart | 13 (4%) |

| Tricuspid atresia | 2 (1%) |

| Tetralogy of Fallot | 29 (10%) |

| Pulmonary atresia without Ventricular Septal Defect | 3 (1%) |

| Double Outlet Right Ventricle | 6 (2%) |

| Transposition of the Great Arteries | 28 (9%) |

| Congenitally-corrected Transposition of the Great Arteries | 2 (1%) |

| Coarctation of the aorta | 24 (8%) |

| Atrioventricular Septal Defect | 8 (3%) |

| Atrium Septum Defect, Ostium Primum | 1 (0.3%) |

| Ebstein malformation | 3 (1%) |

| Pulmonary valve abnormality | 26 (9%) |

| Aortic valve abnormality | 60 (20%) |

| Atrium Septal Defect, Ostium Secundum | 43 (14%) |

| Ventricular Septal Defect | 39 (13%) |

| Mitral valve abnormality | 3 (1%) |

| Pulmonary vein abnormality | 5 (2%) |

| Other diagnoses | 9 (3%) |

| Morphologic complexity of Congenital Heart Disease | |

| Simple | 141 (46%) |

| Moderate | 98 (32%) |

| Complex | 67 (22%) |

| Prior heart surgery | |

| No, none | 139 (45%) |

| Yes, ≥1 surgery performed | 167 (55%) |

| Median number of surgeries | 1 |

| Range | 0-7 |

| Prior heart catheter-based interventions | |

| No, none | 173 (57%) |

| Yes, ≥ 1 catheterization performed | 133 (43%) |

| Median number of catheter-based interventions | 0 |

| Range | 0-31 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 226 (74%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 15 (5%) |

| African American | 14 (5%) |

| Asian | 7 (2%) |

| Other | 44 (14%) |

| Highest level of education | |

| Grades K8-12 | 9 (3%) |

| Graduated high school | 101 (33%) |

| Associate’s degree | 18 (6%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 108 (35%) |

| Special education program | 28 (9%) |

| Other | 4 (1%) |

| Unknown, since patient was untraceable | 38 (12%) |

| Medical coverage | |

| Private insurance | 169 (55%) |

| State aid | 53 (17%) |

| Self-pay/no insurance | 5 (2%) |

| Unknown, since patient was untraceable | 79 (26%) |

| Travel distance to nearest ACHD center (miles) | |

| Median | 30 |

| Range | 1-421 |

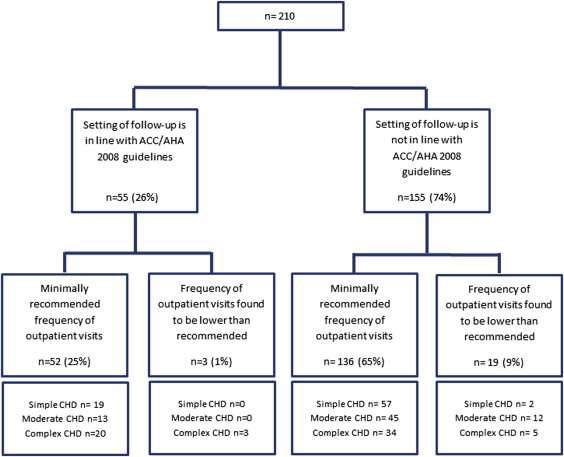

Within the group of patients who were currently in follow-up, only 55 patients (26%) were being seen within an ACHD setting as proposed by the ACC/AHA 2008 recommendations ( Figure 2 ). Most patients currently in follow-up (90%) were being seen at the minimally recommended frequency. Of those followed in ACHD care, the minimally recommended frequency was implemented in 94%. For those in pediatric cardiology, this proportion was 89% (p = 0.412). Taken together, 25% of our sample received care at both a formalized ACHD care setting and at the frequency as proposed by the guidelines based on the anatomical classification of their primary defect ( Figure 2 ). Using multivariable logistic regression analysis, the profile of patients who received care within the proposed setting and at the recommended frequency was explored. None of the demographic/clinical variables were, however, found to be significant predictors for receiving such care ( Table 2 ).

| Predictor variables | B | S.E. | Exp(B) | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | -1.359 | 0.646 | 0.257 | ||

| Sex | 0.185 | 0.339 | 1.203 | 0.619-2.337 | 0.586 |

| Congenital heart disease complexity | |||||

| simple (reference) | – | – | – | – | 0.247 |

| moderate | -0.479 | 0.429 | 0.620 | 0.267-1.436 | 0.264 |

| complex | 0.275 | 0.517 | 1.316 | 0.478-3.627 | 0.595 |

| Travel distance to nearest adult congenital heart disease center | -0.005 | 0.004 | 0.995 | 0.987-1.004 | 0.266 |

| Number of heart surgeries performed in the past | 0.020 | 0.142 | 1.020 | 0.773-1.346 | 0.890 |

| Number of catheter-based interventions performed in the past | 0.015 | 0.052 | 1.015 | 0.917-1.123 | 0.773 |

| Medical insurance ∗ | 0.431 | 0.604 | 1.538 | 0.471-5.025 | 0.476 |

| Ethnicity † | -0.070 | 0.435 | 0.932 | 0.398-2.185 | 0.872 |

∗ 0 indicates no medical insurance or relying on self-pay; 1 indicates patient had medical coverage either through private insurance or state aid.

† 0 indicates patient has white ethnicity; 1 indicates patient has a non-white ethnicity.

Patients who are untraceable require our attention because they may be vulnerable for care gaps. In the group of patients who were untraceable, 65% had a simple defect, 29% were diagnosed with a moderate defect, and 7% had complex CHD. Adults who underwent none or a lower number of surgeries in the past, had no insurance or relied on self-pay, or were of a nonwhite ethnicity had a significantly increased likelihood to become untraceable ( Table 3 ). However, anatomical CHD classification, travel distance to the nearest ACHD center, and the number of previous interventions were not found to be predictive of being untraceable.

| Predictor variables | B | S.E. | Exp(B) | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.849 | 0.408 | 2.337 | ||

| Sex | -0.137 | 0.344 | 0.872 | 0.444-1.713 | 0.692 |

| Congenital heart disease complexity | |||||

| simple (reference) | – | – | – | – | 0.446 |

| moderate | 0.516 | 0.417 | 1.675 | 0.739-3.795 | 0.217 |

| complex | 0.547 | 0.764 | 1.727 | 0.387-7.719 | 0.474 |

| Travel distance to nearest adult congenital heart disease center | -0.009 | 0.005 | 0.991 | 0.982-1.001 | 0.093 |

| Number of heart surgeries performed in the past | -0.924 | 0.307 | 0.397 | 0.218-0.724 | 0.003 |

| Number of catheter-based interventions performed in the past | -0.256 | 0.205 | 0.774 | 0.518-1.157 | 0.212 |

| Medical insurance ∗ | -2.364 | 0.366 | 0.094 | 0.046-0.192 | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity † | 1.093 | 0.361 | 2.983 | 1.470-6.503 | 0.002 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree