Alcohol use, physical activity, diet, and cigarette smoking are modifiable cardiovascular risk factors that have a substantial impact on the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death. We hypothesized that these behaviors may alter concentrations of cardiac troponin, a marker of myocyte injury, and B-type natriuretic peptide, a marker of myocyte stress. Both markers have shown strong association with adverse cardiovascular outcomes. In 519 women with no evidence of cardiovascular disease, we measured circulating concentrations of cardiac troponin T, using a high-sensitivity assay (hsTnT), and the N-terminal fragment of B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP). We used logistic regression to determine if these behaviors were associated with hsTnT ≥3 ng/l or with NT-proBNP in the highest quartile (≥127.3 ng/l). The median (Q1 to Q3) NT-proBNP of the cohort was 68.8 ng/l (40.3 to 127.3 ng/l), and 30.8% (160 of 519) of the cohort had circulating hsTnT ≥3 ng/l. In adjusted models, women who drank 1 to 6 drinks/week had lower odds of having a hsTnT ≥3 ng/l (odds ratio 0.58, 95% confidence interval 0.34 to 0.96) and lower odds of having an elevated NT-proBNP (odds ratio 0.55, 95% confidence interval 0.32 to 0.96). We were subsequently able to validate the results for B-type natriuretic peptide in a large independent cohort. In conclusion, our results suggest that regular alcohol consumption is associated with lower concentrations of hsTnT and NT-proBNP, 2 cardiovascular biomarkers associated with cardiovascular risk, and raise the hypothesis that the beneficial effects of alcohol consumption may be mediated by direct effects on the myocardium.

A substantial portion of the worldwide population attributable risk for myocardial infarction is due to potentially modifiable risk factors, including alcohol consumption, physical activity, diet, and cigarette smoking. The mechanisms by which these behaviors modify cardiovascular risk, however, remain incompletely understood. Prospective studies in the general population have reported strong associations between circulating concentrations of natriuretic peptides (markers of myocyte stress) and cardiac troponin (a marker of myocyte injury) and adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Published data on the effects of alcohol consumption, physical activity, diet, and cigarette smoking on these markers of myocardial stress and injury are scarce. Although alcohol consumption has been associated with a significant increase in baseline B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) in binge drinkers, other studies have reported no relation, and we are not aware of any published studies on the relation between alcohol consumption and cardiac troponin in healthy individuals. Regular physical activity appears to blunt the age-associated increases observed in cardiac troponin T and the N-terminal fragment of B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP). Data for cigarette smoking and diet are similarly scarce. We sought to systematically examine the effects of alcohol consumption, regular physical activity, diet, and smoking on a marker of myocardial stress (NT-proBNP) and a marker of myocardial injury (troponin T) in a cohort of 519 apparently healthy women from the Women’s Health Study.

Methods

Women included in this study were enrolled in the Women’s Health Study (WHS), a completed, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 2 × 2 factorial trial of aspirin and vitamin E in the prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. The WHS enrolled 39,876 female health professionals without coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, or cancer, 19,871 of whom provided a fasting blood sample before randomization. The 519 white women included in this study were an age-stratified sample of these 19,871 women who had adequate blood sample volume available for measurement of NT-proBNP and cardiac troponin T. This sample is part of a larger WHS substudy that is described in detail elsewhere.

Both NT-proBNP and cardiac troponin T were measured using an electrochemiluminescent immunoassay from Roche Diagnostics. The assay used to measure NT-proBNP is commercially available and has day-to-day variability of 3.2%, 2.4%, and 2.2%, at concentrations of 175, 434, and 6,781 ng/l. We used a novel, high-sensitivity assay for cardiac troponin T (hsTnT) that has a limit of blank of 3 ng/l. The 99th percentile in a healthy population is <14 ng/l, and the concentration at which the assay has a 10% coefficient of variation is reported to be less than this value.

At enrollment, women were asked to estimate the time per week during the past year they spent on walking, jogging, running, biking, aerobic exercise or dance, racquet sports, lap swimming, weight lifting, and yoga or stretching. The questionnaire used to collect this information has shown to be reliable and valid. A metabolic equivalent (MET) task score was assigned to each activity, and the energy expended was determined by multiplying the MET score by the hours spent on the physical activity. The sum of these energies represented total energy expenditure and was used to calculate the total energy expended by the patient per week (MET hours/week) during the year before study entry.

A validated semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire was used to collect consumption (frequency and type) of dairy foods, fruits and vegetables, eggs and meat, breads, cereals and starches, sweets and baked goods, and beverages over the past year. The diet data were used to calculate an Alternative Healthy Eating Index–2010 (AHEI-2010) score. The calculation of the AHEI-2010 score has been described previously. We excluded alcohol use in our calculation as we decided a priori to include alcohol as a separate modifiable risk factor. AHEI scores both including and excluding alcohol have shown to inversely associate with risk of coronary heart disease. Cigarette consumption and alcohol use were also collected via questionnaire.

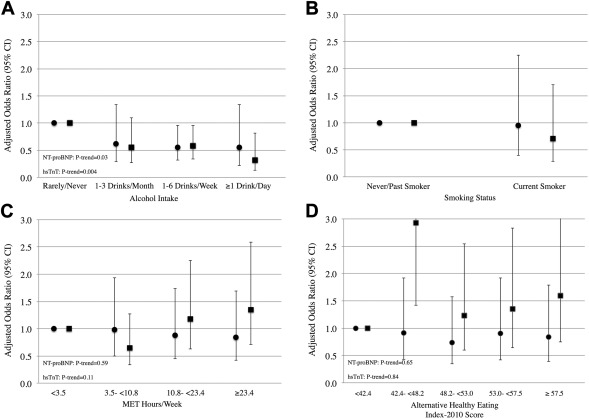

Based on the data collected, physical activity was split into quartiles (<3.5 MET hours/week, 3.5 to <10.8 MET hours/week, 10.8 to <23.4 MET hours/week, ≥23.4 MET hours/week). AHEI-2010 score was split into quintiles (<42.4, 42.4 to <48.2, 48.2 to <53.0, 53.0 to <57.5, ≥57.5). Alcohol was split into categories of “Rarely/Never,” “1 to 3 drinks/month,” “1 to 6 drinks/week,” or “≥1 drink/day”. Smoking status was coded as “Never/Past” or “Current.”

NT-proBNP concentrations were divided into increasing quartiles and continuous and categorical baseline characteristics were compared across NT-proBNP quartile using Jonckheere–Terpstra and Cochran–Armitage tests, respectively. Baseline characteristics for women with hsTnT concentrations ≥3 ng/l were compared to those with hsTnT concentrations < 3 ng/l using Wilcoxon rank-sum and chi-square tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Our primary analysis used logistic regression to test for associations between the 4 modifiable behaviors and either a prospectively defined abnormal NT-proBNP (≥127.3 ng/l) or hsTnT ≥3 ng/l. An abnormal NT-proBNP was prospectively defined as the top quartile (≥127.3 ng/l) of the distribution in our population of initially healthy middle-aged women. Thresholds lower than this have been associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes in this cohort. Logistic regression models were adjusted for age (model 1); age, body mass index, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, history of hypertension, triglycerides, postmenopausal status, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (model 2); and the model 2 co-variables plus physical activity, alcohol use, smoking status, and AHEI-2010 score (model 3).

We validated our observations in a subcohort of the Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: An Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin (JUPITER) study. The JUPITER subcohort contains 12,951 men and women with high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (hsTnI) and 11,052 men and women with B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) measurements available. All participants in the cohort were initially free of cardiovascular disease. Baseline characteristics of the cohort have been previously described. In JUPITER, we calculated tertiles separately in men and women and used logistic regression to test for associations between alcohol use and odds of having a BNP in the highest tertile (≥28.6 ng/l for men, ≥44.4 ng/l for women) or hsTnI in the highest tertile (≥4.6 ng/l in men, ≥3.9 ng/l in women). BNP and hsTnI values in the highest tertile have been shown to associate with increased risk of first major cardiovascular event in this cohort. Models were adjusted for age, race, and sex (model 1); age, race, sex, body mass index, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, history of hypertension, triglycerides, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (model 2); and the co-variables in model 2 plus alcohol use, physical activity, and smoking status (model 3).

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc.).

Results

The median (Q1 to Q3) age of the study population was 57.2 years (51.2 to 64.5), and the median (Q1 to Q3) NT-proBNP concentration was 68.8 ng/l (40.3 to 127.3 ng/l). Baseline characteristics of the women, stratified by quartile of NT-proBNP concentration, are displayed in Table 1 . As can be seen, higher concentrations of NT-proBNP are associated with older age and higher high-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations and lower body mass index, total cholesterol, triglycerides, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Women with hsTnT ≥3 ng/l were older and had a higher prevalence of hypertension and a lower prevalence of current smoking compared to women with hsTnT <3 ng/l ( Table 2 ).

| Variable | NT-proBNP Quartile | P-Value ∗ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (n=129) | 2 (n=130) | 3 (n=130) | 4 (n=130) | ||

| NT-pro BNP (ng/l) | <40.3 | 40.3 – < 68.8 | 68.8 – <127.3 | ≥127.3 | |

| Age (years) | 54.3 (49.0-58.9) | 54.7 (49.4-61.5) | 59.7 (53.0-66.2) | 63.3 (55.5-68.8) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 40 (31.0%) | 29 (22.3%) | 39 (30.0%) | 51 (39.2%) | 0.07 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | 125 (115-135) | 125 (115-135) | 125 (115-135) | 125 (115-145) | 0.18 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m 2 ) | 26.6 (23.9-30.6) | 25.5 (22.5-27.4) | 25.0 (22.8-28.3) | 24.6 (22.1-27.1) | <0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 51 (39.5%) | 43 (33.1%) | 35 (26.9%) | 45 (34.6%) | 0.26 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 221.0 (202.0-250.0) | 217.5 (187.0-246.0) | 211.0 (186.0-238.0) | 209.0 (186.0-233.5) | 0.003 |

| Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 133.5 (115.2-159.6) | 127.5 (102.1-153.0) | 124.2 (101.9-144.4) | 123.2 (101.5-145.3) | 0.002 |

| High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 46.6 (41.0-56.0) | 52.9 (43.4-63.2) | 56.4 (44.5-65.0) | 52.2 (44.1-61.7) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 138.0 (98.0-211.0) | 127.5 (83.0-174.0) | 114.0 (81.0-169.0) | 114.5 (82.5-158.5) | 0.005 |

| Postmenopausal | 78 (60.5%) | 84 (65.0%) | 99 (76.2%) | 103 (79.2%) | <0.001 |

| Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (ml/min/1.73m 2 ) | 100.0 (82.7-128.5) | 94.9 (77.4-110.8) | 87.6 (75.8-106.2) | 87.1 (70.1-101.6) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol Consumption | 0.17 | ||||

| Rarely/Never | 65 (50.4%) | 57 (43.9%) | 53 (40.8%) | 71 (54.6%) | |

| 1-3 Drinks/Month | 19 (14.7%) | 18 (13.9%) | 13 (10.0%) | 14 (10.8%) | |

| 1-6 Drinks/Week | 39 (30.2%) | 46 (35.4%) | 48 (36.9%) | 34 (26.2%) | |

| ≥1 Drink/Day | 6 (4.7%) | 9 (6.9%) | 16 (12.3%) | 11 (8.5%) | |

| Alcohol (drinks/day) | 0.0 (0.0-0.2) | 0.1 (0.0-0.4) | 0.1 (0.0-0.5) | 0.0 (0.0-0.2) | 0.99 |

| Alcohol (grams/day) | 0.0 (0.0-2.9) | 1.1 (0.0-4.6) | 1.2 (0.0-5.9) | 0.0 (0.0-2.3) | 0.99 |

| Physical Activity (Metabolic Equivalent hours/week) | 8.4 (2.5-23.1) | 13.0 (4.4-22.6) | 10.2 (5.0-24.2) | 11.4 (3.5-24.0) | 0.42 |

| Alternate Healthy Eating Index-2010 Score | 51.4 (44.4-56.4) | 50.0 (42.3-57.2) | 51.0 (44.7-55.9) | 49.2 (42.9-55.9) | 0.72 |

| Current Smoker | 14 (10.9%) | 17 (13.1%) | 9 (6.9%) | 11 (8.5%) | 0.25 |

∗ Continuous variables compared across quartiles of NT-proBNP using Jonckheere-Terpstra test. Categorical variables compared across quartiles of NT-proBNP using Cochran-Armitage test.

| Variable | hsTnT ≥3 ng/l | P-Value ∗ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n=359) | Yes (n=160) | ||

| Age (years) | 55.8 (50.3-63.2) | 61.0 (53.8-67.3) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 98 (27.3%) | 61 (38.1%) | 0.01 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | 125.0 (115.0-135.0) | 125.0 (115.0-135.0) | 0.02 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m 2 ) | 25.1 (22.7-28.2) | 25.8 (23.3-29.1) | 0.06 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 113 (31.5%) | 61 (38.1%) | 0.14 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 218.0 (189.0-246.0) | 211.5 (187.0-233.0) | 0.05 |

| Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 127.2 (107.6-151.9) | 124.2 (106.5-144.7) | 0.30 |

| High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 52.0 (43.8-62.9) | 49.3 (41.8-60.4) | 0.06 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 124.0 (86.0-184.0) | 116.0 (82.0-161.0) | 0.19 |

| Postmenopausal | 240 (66.9%) | 124 (78.0%) | 0.01 |

| Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (ml/min/1.73m 2 ) | 92.5 (76.6-109.1) | 92.5 (74.8-113.1) | 0.98 |

| Alcohol Consumption | 0.05 | ||

| Rarely/Never | 156 (43.5%) | 90 (56.3%) | |

| 1-3 Drinks/Month | 47 (13.1%) | 17 (10.6%) | |

| 1-6 Drinks/Week | 123 (34.3%) | 44 (27.5%) | |

| ≥1 Drink/Day | 33 (9.2%) | 9 (5.6%) | |

| Alcohol (drinks/day) | 0.1 (0.0-0.4) | 0.0 (0.0-0.2) | 0.003 |

| Alcohol (grams/day) | 1.1 (0.0-5.1) | 0.0 (0.0-2.0) | 0.003 |

| Physical Activity (Metabolic Equivalent hours/week) | 10.3 (3.8-22.5) | 12.6 (2.9-26.3) | 0.55 |

| Alternative Healthy Eating Index-2010 Score | 50.9 (43.1-56.1) | 49.3 (43.9-57.0) | 0.95 |

| Current Smoker | 42 (11.7%) | 9 (5.6%) | 0.03 |

∗ Continuous variables compared using Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test, and categorical variables compared using Chi-Square test.

The associations between alcohol consumption and an elevated NT-proBNP or hsTnT ≥3 ng/l are presented in Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1 . In adjusted models (model 3), we observed that women who drank 1 to 6 drinks/week had 45% lower odds of having an elevated NT-proBNP compared to women who rarely or never drink. Additionally, women who drank 1 to 6 drinks/week had 42% lower odds of having a hsTnT ≥3 ng/l, and women who drank ≥1 drink/day had 68% lower odds of having a hsTnT ≥3 ng/l compared to women who rarely or never drink (p trend: 0.004; Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1 ).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree