Coronary artery bypass grafting is pivotal in the contemporary management of complex coronary artery disease. Interpatient variability to antiplatelet agents, however, harbors the potential to compromise the revascularization benefit by increasing the incidence of adverse events. This study was designed to define the impact of dual antiplatelet therapy (dAPT) on clinical outcomes among aspirin-resistant patients who underwent coronary artery surgery. We randomly assigned 219 aspirin-resistant patients according to multiple electrode aggregometry to receive clopidogrel (75 mg) plus aspirin (300 mg) or aspirin-monotherapy (300 mg). The primary end point was a composite outcome of all-cause death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular hospitalization assessed at 6 months postoperatively. The primary end point occurred in 6% of patients assigned to dAPT and 10% of patients randomized to aspirin-monotherapy (relative risk 0.61, 95% confidence interval 0.25 to 1.51, p = 0.33). No significant treatment effect was noted in the occurrence of the safety end point. The total incidence of bleeding events was 25% and 19% in the dAPT and aspirin-monotherapy groups, respectively (relative risk 1.34, 95% confidence interval 0.80 to 2.23, p = 0.33). In the subgroup analysis, dAPT led to lower rates of adverse events in patients with a body mass index >30 kg/m 2 (0% vs 18%, p <0.01) and those <65 years (0% vs 10%, p = 0.02). In conclusion, the addition of clopidogrel in patients found to be aspirin resistant after coronary artery bypass grafting did not reduce the incidence of adverse events, nor did it increase the number of recorded bleeding events. dAPT did, however, lower the incidence of the primary end point in obese patients and those <65 years.

Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) remains the standard of care in the management of complex coronary artery disease. Improvements in postoperative outcomes rely both on technical refinements of the procedure and optimization of medical management. The long-term benefits of CABG depend upon the durability of nonobstructed flow through bypass grafts. Inhibition of platelet aggregability plays a crucial role in improving graft patency. Aspirin is currently the most commonly employed antiplatelet agent after CABG. Dual antiplatelet therapy (dAPT) may improve the venous graft patency, but this benefit has not been reliably reproduced in a wider clinical arena. The combination of clopidogrel and aspirin results in the cumulation of their individual antiaggregatory effects, because their individual mechanisms of antiplatelet activity differ. Dual platelet inhibition may be of particular importance in patients exhibiting single antiplatelet drug resistance. Defining the role of dAPT in the contemporary surgical practice is paramount before recommending it without reservations, however, as it may increase the incidence of bleeding. The incidence of low response to aspirin is not uniform across the available spectrum of platelet function tests. It has been reported to range from 1% to 45%. Although clear outlines of this phenomenon remain to be defined, its adverse clinical impact has been validated. We hypothesized that augmentation of platelet inhibition with clopidogrel in patients with high postoperative on-aspirin platelet reactivity would lead to improvement in clinical outcomes. The convergence of the clinical impact of aspirin resistance with the beneficial effects of dAPT in other clinical scenarios was the foundation of this trial’s design. This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first prospective randomized study that selectively implemented dAPT after CABG in patients with aggregometry-documented aspirin resistance.

Methods

The study was conducted at the University Hospital Center Zagreb in Zagreb, Croatia. Patient enrollment started in June 2010 and was completed in February 2013. Details of the study design, eligibility, and exclusion criteria have been published previously. Briefly, adult patients scheduled to undergo elective primary CABG were eligible for enrollment. Exclusion criteria included valvular pathology warranting surgical correction, off-pump CABG, requirement for dual antiplatelet management, anticoagulation, and critical condition before randomization. Patients who underwent CABG following a recent acute coronary syndrome were excluded, as there are data to suggest that they might benefit from dAPT. On postoperative day (POD) 4, patients underwent an aggregometry-based assessment of their on-aspirin platelet reactivity. Patients found to be aspirin responders were excluded from further analysis, whereas aspirin-resistant patients were randomized into either the control or intervention groups.

The trial was approved by the Ethics committee of the University Hospital Center Zagreb. Ethical standards in line with the Declaration of Helsinki were adhered to. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before enrollment.

Multiple electrode aggregometry was used for quantifying platelet reactivity in the study cohort (Multiplate, Dynabyte, Munich, Germany). Platelet aggregation, as evaluated by multiple electrode aggregometry, is responsible for the variability in sensor wire impedances. The numerical multiple electrode aggregometry output describes the electrical resistance between sensor wires, which is proportional to platelet adherence. Arachidonic acid (0.5 mM) and adenosine diphosphate (ADP, 6.4 μM) were utilized as platelet agonists for conducting the ASPI and ADP tests, respectively.

The ASPI test evaluates cyclooxygenase-1-dependent platelet aggregation and is therefore a surrogate for aspirin responsiveness. Although aspirin response is better described as a continuous variable, dichotomizing patients into “responders” and “nonresponders” is commonly utilized for research purposes. Aspirin resistance in the present study was defined in line with previous reports stratifying individual patient responsiveness into quartiles. Patients were classified as aspirin resistant if their ASPI test values exceeded the population’s 75th percentile cut-off point (area under the curve [AUC] ≥30). This definition was substantiated by data from multiple other sources.

Having met the inclusion criteria for aspirin resistance on POD 4, patients scheduled for isolated CABG were randomly allocated into either continuation on 300 mg of aspirin (control group) or enhancement of platelet inhibition with 75 mg of clopidogrel plus 300 mg of aspirin (dAPT group). Randomization software was used for patient allocation into the control or intervention arms.

Preoperative platelet inhibition with aspirin was maintained up to the day of surgery. Conversely, patients receiving preoperative clopidogrel had the drug discontinued approximately 5 days before the surgical procedure. Tepid cardiopulmonary bypass and cardioplegic arrest were used in all study patients. Myocardial preservation was based on a combination of anterograde and retrograde cardioplegia. Postoperatively, patients typically received a β blocker, hydroxy-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitor, peptic ulcer prophylaxis, and a diuretic. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors were administered selectively and titrated to effect. Aspirin was typically administered within the first 6 hours of surgery. In aspirin nonresponders, the postoperative antiplatelet regime was then re-evaluated on POD 4 in line with the study protocol.

The primary efficacy end point was the incidence of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCEs) at 6 months. MACCE was a composite outcome including all-cause mortality, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), cerebrovascular accident, and cardiovascular rehospitalization. The secondary outcomes were bleeding events and individual MACCE components. We adhered to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium definitions in presenting the safety end point data. The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association/World Heart Federation Task Force for the redefinition of MI was implemented in patients suspected to have ischemic myocardial injury. Patients with new focal neurologic deficits lasting >24 hours or those having an acute cerebral lesion on an imaging study were considered to have had a stroke.

The study was designed to analyze the incidence of MACCE at 6 months, on an intention-to-treat basis, in aspirin-resistant patients randomized to either continue on aspirin monotherapy or receive dual inhibition of platelet aggregation. The sample size required to test the null hypothesis was determined by an exact binomial test power analysis. The minimum effect size was 10%. Accounting for an estimated 10% loss to follow-up, 219 patients were required to test the null hypothesis with an α value of 0.05 and a power of 0.8. An additional per-protocol analysis of the safety end point was performed in patients adhering to the study protocol. The continuous data are presented as mean values with their standard deviation. Categorical variables are presented as absolute numbers with percentages. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyze continuous data between the control and intervention groups. Comparisons among categorical variables were performed with Fisher’s exact test. Changes in the platelet reactivity in response to surgery were evaluated with the Wilcoxon matched-pairs test. Relative risks (RRs) were used as a measure of the association between the intervention and clinical outcomes. The respective 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were provided. A two-tailed p value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant for all deployed calculations. Additional one-tailed p values were also obtained and provided for comparisons likely to result in one-directional relationships. The data were processed using the IBM SPSS Statistics software package (version 20.0; Somers, New York) and Statpages.org .

Results

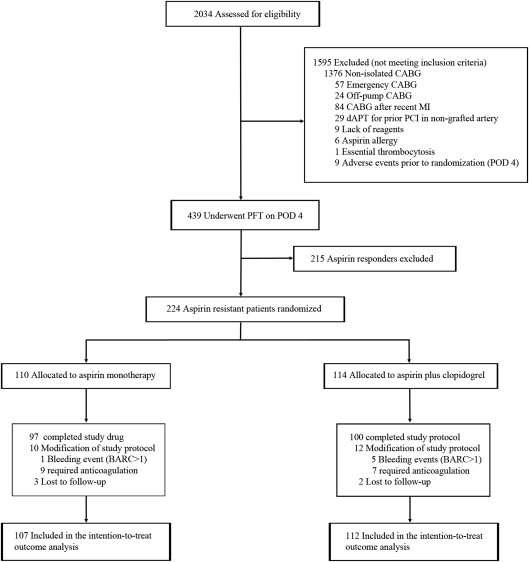

During the recruitment period, 2,034 patients were screened for eligibility. A total of 224 aspirin-resistant patients with CABG were randomly assigned to receive aspirin only (n = 110) or aspirin plus clopidogrel (n = 114). An overview of the patient enrollment and randomization is shown in Figure 1 . The baseline patient demographic and clinical profiles were well balanced between the 2 groups ( Table 1 ). Approximately, 3/4 of the patients were men, and the majority of them had three-vessel disease, which is representative of the contemporary cardiac surgical practice. Beta blockers were utilized more commonly in the dAPT group before surgery. The use of other preoperative medications, including antiplatelet agents, did not differ significantly between the groups ( Table 1 ). Perioperative data are listed in Table 2 . Postoperative medication regimes did not differ between the groups with the notable exception of clopidogrel utilization, which was subject to the randomization protocol ( Table 2 ).

| Variable | Aspirin Monotherapy (n = 107) | Aspirin Plus Clopidogrel (n = 112) | p ∗ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 65 ± 9 | 65 ± 8 | 0.69 |

| Male gender | 82 (77) | 83 (74) | 0.75 |

| BMI (kg/m 2 ) | 30 ± 4 | 29 ± 4 | 0.21 |

| EuroSCORE | 3.6 ± 3.7 | 3.5 ± 3.0 | 0.44 |

| LVEF (%) | 55 ± 10 | 53 ± 10 | 0.16 |

| Hyperlipidemia † | 103 (96) | 108 (96) | 1.00 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 41 (38) | 43 (38) | 1.00 |

| Smoker | 41 (38) | 38 (34) | 0.57 |

| Hypertension ‡ | 103 (96) | 108 (96) | 1.00 |

| Left main narrowing | 57 (53) | 48 (43) | 0.14 |

| Three-vessel coronary disease | 80 (75) | 88 (79) | 0.53 |

| Preoperative platelet reactivity | |||

| ASPI test values, AUC | 38 ± 28 | 35 ± 30 | 0.27 |

| ADP test values, AUC | 80 ± 25 | 77 ± 26 | 0.47 |

| Preoperative medications | |||

| Clopidogrel | 27 (25) | 37 (33) | 0.24 |

| Aspirin | 94 (88) | 100 (89) | 0.83 |

| β blocker | 83 (78) | 101 (90) | 0.02 |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor | 67 (63) | 61 (54) | 0.27 |

| Statin | 104 (97) | 108 (96) | 1.00 |

† Hyperlipidemia was defined as any of the following: history of hypercholesterolemia (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol >3.4 mmol/L or total cholesterol >5.2 mmol/L), hypertriglyceridemia (>1.7 mmol/L), hyperchylomicronemia or use of lipid-lowering medications to achieve target lipid/lipoprotein values.

‡ Hypertension was defined as 2 or more systolic BP measurements ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic BP readings ≥90 mm Hg, or use of antihypertensive medications to achieve the desired BP values in patients with a history of high BP.

| Aspirin Monotherapy (n = 107) | Aspirin Plus Clopidogrel (n = 112) | p ∗ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perioperative data | |||

| Left internal mammary use | 101 (94) | 104 (93) | 0.78 |

| Cross-clamp time (minutes) | 57 ± 22 | 59 ± 22 | 0.45 |

| CPB time (minutes) | 86 ± 25 | 87 ± 28 | 0.62 |

| Postoperative AF | 27 (25) | 36 (32) | 0.30 |

| Postoperative inotrope use | 31 (29) | 36 (32) | 0.66 |

| Postoperative platelet reactivity | |||

| ASPI test values, AUC | 53 ± 22 | 60 ± 29 | 0.19 |

| ADP test values, AUC | 97 ± 31 | 95 ± 34 | 0.89 |

| Postoperative medications | |||

| Clopidogrel | 0 | 112 (100) | <0.01 |

| Aspirin | 107 (100) | 112 (100) | 1.00 |

| β blocker | 101 (94) | 101 (90) | 0.31 |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor | 12 (11) | 17 (15) | 0.43 |

| Statin | 100 (93) | 104 (93) | 1.00 |

There were no differences in preoperative platelet aggregability between the groups ( Table 1 ). The ASPI test values evaluated on POD 4 were also comparable between the control and intervention groups ( Table 2 ). Postoperative ASPI test values in both patient groups were well above the predefined 30 AUC cut-off points discriminating between aspirin response and resistance. Analogously, the postoperative ADP test values did not differ between the groups ( Table 2 ). We have, however, documented a significant postprocedural rise in platelet reactivity in comparison with the respective preoperative values. The ASPI test values across the entire cohort increased from 36 ± 29 to 57 ± 26 AUC (p <0.001). This accelerated platelet aggregability was corroborated by an increase in the ADP values (preoperatively: 78 ± 26; postoperatively: 96 ± 33 AUC, p <0.001). Additional evidence for a hypercoagulable state in the early postoperative period was found in the dynamics of fibrinogen levels. We documented a consistent and statistically significant increase in fibrinogen concentrations in response to the surgical procedure (4.1 ± 1.3 vs 6.8 ± 1.4 g/L, p <0.001). The observed increase in platelet aggregability was seen in both groups, irrespective of the antiplatelet management strategy ( Figure 2 ).

Six-month follow-up was completed in 107 (97%) and 112 (98%) patients in the aspirin monotherapy and dAPT groups, respectively. The study outcomes are listed in Table 3 . Freedom from MACCE at the completion of the follow-up period was 90% in the control group and 94% in the dAPT group. The overall incidence of the primary end point was not affected by the different antiplatelet management protocols (6% vs 10%; RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.51, two-tailed p = 0.33, one-tailed p = 0.20). A nonsignificant 43% RR reduction in the composite end point of MI/stroke/cardiovascular death was observed with enhancement of platelet inhibition (two-tailed p = 0.49, one-tailed p = 0.34). The frequency of individual MACCE components was not affected by the antiplatelet management strategy ( Table 3 ). The causes of death in the 4 control group patients were stroke, sepsis, necrotizing tracheitis, and trauma. Two patients in the dAPT group died during follow-up. One suffered a stroke that eventually led to his death, whereas the other died of intractable respiratory failure induced by pneumonia.

| Aspirin Monotherapy (n = 107) | Aspirin Plus Clopidogrel (n = 112) | RR (95% CI) | p ∗ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficacy end points | ||||

| MACCE | 11 (10) | 7 (6) | 0.61 (0.25–1.51) | 0.33 |

| All-cause death | 4 (4) | 2 (2) | 0.48 (0.09–2.55) | 0.44 |

| Cardiovascular death | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.96 (0.06–15.08) | 1.00 |

| Stroke | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 0.24 (0.03–2.10) | 0.20 |

| Nonfatal MI | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.96 (0.06–15.08) | 1.00 |

| Composite MI or stroke or cardiovascular death | 5 (5) | 3 (3) | 0.57 (0.14–2.34) | 0.49 |

| Cardiovascular hospitalization | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 0.96 (0.20–4.63) | 1.00 |

| Safety end points | ||||

| Total bleeding events | 20 (19) | 28 (25) | 1.34 (0.80–2.23) | 0.33 |

| BARC 1 | 19 (18) | 23 (21) | 1.16 (0.67–2.00) | 0.61 |

| BARC 2 | 0 | 1 (1) | N/A | 1.00 |

| BARC 3 | 1 (1) | 4 (4) | 3.82 (0.43–33.65) | 0.37 |

| BARC 4 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 1.00 |

| BARC 5 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 1.00 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree