Atrial fibrillation (AF) has been associated with worse outcomes after primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for acute myocardial infarction. The aim of this study was to evaluate the incidence and impact of new-onset AF after primary PCI in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarctions from the Harmonizing Outcomes With Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction (HORIZONS-AMI) trial. HORIZONS-AMI was a large-scale, multicenter, international, randomized trial comparing different antithrombotic regimens and stents during primary PCI in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarctions. Three-year ischemic and bleeding end points were compared between patients with and without new-onset AF after PCI. Of the 3,602 patients included in the HORIZONS-AMI study, 3,281 (91.1%) with sinus rhythm at initial presentation had primary PCI as their primary management strategy. Of these, new-onset AF developed in 147 (4.5%). Compared with patients without AF after PCI, patients with new-onset AF had higher 3-year rates of net adverse clinical events (46.5% vs 25.7%, p <0.0001), mortality (11.9% vs 6.3%, p = 0.01), reinfarction (16.4% vs 7.0%, p <0.0001), stroke (5.8% vs 1.5%, p <0.0001), and major bleeding (20.9% vs 8.2%, p <0.0001). By multivariate analysis, new-onset AF after PCI was a powerful independent predictor of net adverse clinical events (hazard ratio 1.74, 95% confidence interval 1.30 to 2.34, p = 0.0002) and major adverse cardiac events (hazard ratio 1.73, 95% confidence interval 1.27 to 2.36) at 3 years. In conclusion, new-onset AF after PCI for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction was associated with markedly higher rates of adverse events and mortality.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) occurs in 6% to 11% of patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarctions (STEMIs) and has been associated with increased in-hospital and long-term mortality rates since the prethrombolytic and thrombolytic eras. Although primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is now the preferred management strategy in patients presenting with STEMIs, there are scant data from large studies assessing the impact of new-onset AF in patients who are treated invasively. We therefore investigated the incidence and impact of new-onset AF after primary PCI in patients presenting with STEMIs from the large randomized Harmonizing Outcomes With Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction (HORIZONS-AMI) trial.

Methods

The design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and end point definition of the HORIZONS-AMI trial have previously been described in detail. In brief, the HORIZONS-AMI trial was a prospective, open-label, multicenter trial involving patients with STEMIs who underwent primary PCI as a management strategy. Patients with STEMIs presenting within 12 hours of symptom onset were randomized (1:1) to receive either unfractionated heparin plus glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor or bivalirudin monotherapy (plus bailout glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor) before primary PCI. Immediate coronary angiography was performed after randomization, followed by PCI, coronary artery bypass grafting, or medical management at the discretion of the physician. In a second randomization strategy, patients eligible for stenting were randomized (3:1) to receive TAXUS Express 2 paclitaxel-eluting stents (Boston Scientific Corporation, Natick, Massachusetts) or to an otherwise identical Express bare-metal stent (Boston Scientific Corporation). Clinical follow-up was performed at 30 days, 6 months, 1 year, 2 years, and 3 years. Use of warfarin or any long-term oral anticoagulation before randomization and major contraindication to long-term anticoagulation were major exclusion criteria to the HORIZONS-AMI study.

AF was defined as the absence of P waves and atrial activity represented by fibrillatory waves and irregular RR intervals. Patients were classified as having new-onset AF if they had no AF at presentation and no history of AF (including a history of paroxysmal AF) but had ≥1 episode of AF recorded on electrocardiography or telemetry during the index hospitalization after PCI (as reviewed by an independent electrocardiography core laboratory of the Cardiovascular Research Foundation, New York, New York). The primary end point of the present study was net adverse clinical events (NACEs), defined as the combination of major bleeding (unrelated to coronary artery bypass grafting) or a composite of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs), including death, reinfarction, target vessel revascularization for ischemia, and stroke. All events were adjudicated by an independent clinical events committee blinded to treatment assignment. Patients with and without new-onset AF after PCI were compared at 3 years with respect to MACEs, NACEs, and their individual components.

All analyses were performed by intention to treat. Chi-square tests were used to compare categorical variables, which are presented as proportions. Continuous variables were compared using Wilcoxon’s rank-sum tests and are presented as medians with interquartile ranges. Follow-up analysis was performed using time-to-event data, estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and were compared using the log-rank test. A stepwise logistic regression model with an entry and exit level of significance of 0.10 was used to identify independent predictors of new-onset AF. Potential covariates included in this regression model were age, male gender, body mass index, history of smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, previous myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, New York Heart Association class III, peripheral vascular disease, chronic renal insufficiency, and ≥2-vessel coronary artery disease. Cox multivariate regression models were used to identify independent predictors of NACEs, MACEs, and death at 3 years. Variables included in the Cox regression models were age, hypertension, history of smoking, diabetes, previous myocardial infarction, previous PCI, left anterior descending coronary artery as the culprit vessel, symptom onset–to–balloon time, congestive heart failure, New York Heart Association class III, history of ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation, thienopyridine use, and chronic renal insufficiency. Variables included in the models were carefully selected to avoid overfitting. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Of the 3,343 patients with STEMIs who underwent primary PCI, 62 (1.9%) presented with AF at baseline and were excluded from the present analysis. Of the total studied population of 3,281 patients, post-PCI new-onset AF developed in 147 (4.5%) of patients.

Compared with patients without AF after PCI, patients with new-onset AF were older, were more often women, and had lower ejection fractions at baseline ( Table 1 ). There was no difference in the rate of postprocedural TIMI grade 3 flow achieved between the 2 groups at the end of the index PCI. Patients in the new-onset AF group were less likely to be discharged on thienopyridine (94% vs 98%, p = 0.002) but, as expected, were more likely to be discharged on warfarin (11% vs 3%) and amiodarone (20% vs 1%) (p <0.0001 for both).

| Variable | New-Onset AF | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 147) | No (n = 3,134) | ||

| Age (yrs) | 69.3 (60.1–75.2) | 59.4 (52.2–68.9) | <0.0001 |

| Men | 100/147 (68%) | 2,434/3,134 (78%) | 0.007 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 23/147 (16%) | 502/313 (16%) | 0.90 |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) | 27.2 (25.0–30.1) | 27.1 (24.5–30.2) | 0.30 |

| Hypertension ∗ | 82/147 (56%) | 1,638/3,134 (52%) | 0.40 |

| Hyperlipidemia † | 61/147 (42%) | 1,345/3,134 (43%) | 0.73 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 14/147 (10%) | 327/3,134 (10%) | 0.72 |

| Previous coronary intervention | 15/147 (10%) | 326/3,134 (10%) | 0.94 |

| Previous coronary bypass | 3/147 (2%) | 84/3,134 (3%) | 1.00 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 46% (40%–55%) | 50% (43%–59%) | 0.004 |

| Ejection fraction <40% | 24/121 (20%) | 379/2,665 (14%) | 0.09 |

| ≥2-vessel coronary artery disease | 48/146 (33%) | 1,078/3,088 (35%) | 0.61 |

| Chronic renal insufficiency | 8/147 (5%) | 79/3,133 (3%) | 0.06 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 10/147 (7%) | 132/3,133 (4%) | 0.13 |

| Door-to-balloon time (minutes) | 100.0 (71.0–130.0) | 98.5 (73.0–135.0) | 0.57 |

| Index PCI vessel | |||

| Left anterior descending coronary artery | 59/156 (38%) | 1,361/3,352 (41%) | 0.49 |

| Left circumflex coronary artery | 26/156 (17%) | 532/3,352 (16%) | 0.79 |

| Right coronary artery | 68/156 (44%) | 1406/3,352 (42%) | 0.68 |

| Left main coronary artery | 1/156 (0.6%) | 19/3,352 (0.6%) | 0.60 |

| Drug-eluting stents | 85/129 (66%) | 2,133/2,949 (72%) | 0.11 |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors | 96/147 (65%) | 1,742/3,130 (56%) | 0.02 |

| Bivalirudin in catheterization laboratory | 68/147 (46%) | 1,563/3,124 (50%) | 0.37 |

| Baseline TIMI flow grade 0/1 | 105/156 (67%) | 2,194/3,341 (66%) | 0.67 |

| Postprocedural TIMI grade 3 flow | 143/156 (92%) | 3,069/3,346 (92%) | 0.98 |

| Postprocedural blush grade 3 | 86/115 (75%) | 1,980/2,623 (76%) | 0.86 |

∗ History of and/or current hypertension (high arterial blood pressure) diagnosed per local standard criteria.

† History of and/or current hyperlipidemia (hypercholesterolemia and/or hypertriglyceridemia) diagnosed per local standard criteria.

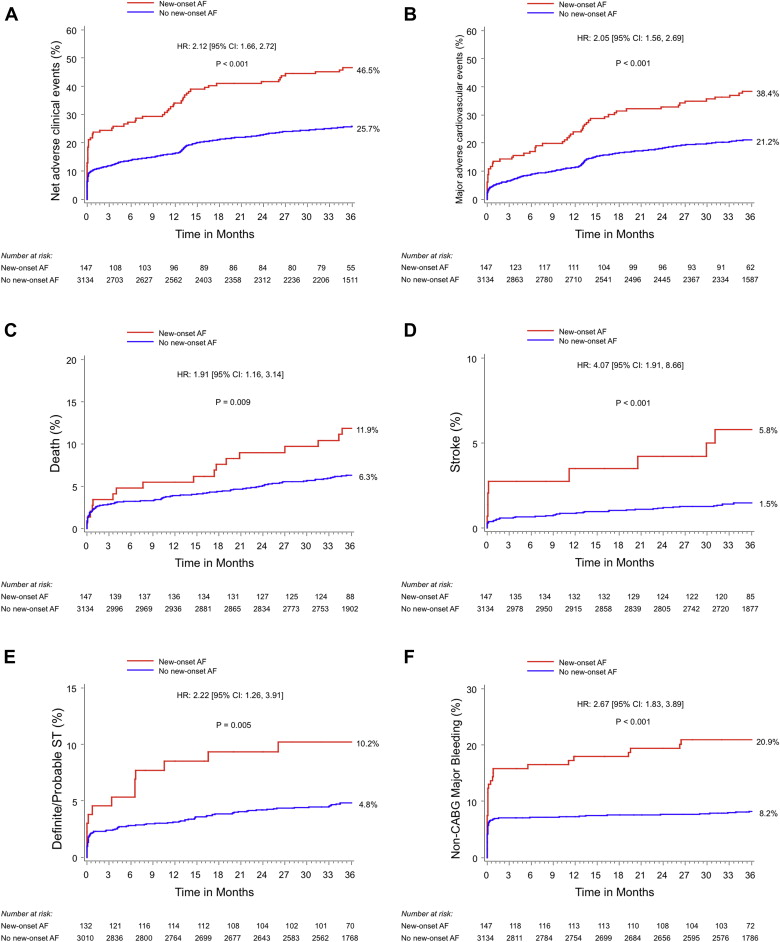

Three-year clinical outcomes in patients with and without new-onset AF after PCI are listed in Table 2 and shown in Figure 1 . Patients with new-onset AF had significantly higher 3-year rates of NACEs (46.5% vs 25.7%, p <0.0001), MACEs (38.4% vs 21.2%, p <0.0001), death (11.9% vs 6.3%, p = 0.009), ischemic stroke (5.8% vs 1.5%, p <0.0001), definite or probable stent thrombosis (10.2% vs 4.8%, p = 0.005), and major bleeding unrelated to coronary artery bypass grafting (20.9% vs 8.2%, p <0.0001). Table 3 lists rates of stent thrombosis according to the types of stent received and according to the occurrence or not of new-onset AF. At 30 days and beyond, patient with new-onset AF after PCI had a higher rate of definite or probable stent thrombosis whether they received bare-metal stents or drug-eluting stents. Notably, patients with new-onset AF after PCI had lower rates of aspirin compliance at 1 year (91.7% vs 97.3%, p = 0.002), 2 years (89.3% vs 96.8%, p = 0.0002), and 3 years (86.2 vs 95.9%, p <0.0001) and lower rates of thienopyridine compliance at 30 days (91.4% vs 97.6%, p = 0.003) and 1 year (56.4% vs 70.5%, p = 0.0005).

| Variable | New-Onset AF | HR (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 147) | No (n = 3,134) | |||

| NACEs | 68 (46.5%) | 790 (25.7%) | 2.12 (1.66–2.72) | <0.0001 |

| MACEs | 56 (38.4%) | 647 (21.2%) | 2.05 (1.56–2.69) | <0.0001 |

| Death | 17 (11.9%) | 192 (6.3%) | 1.91 (1.16–3.14) | 0.009 |

| Cardiac | 9 (6.3%) | 114 (3.7%) | 1.70 (0.86–3.34) | 0.12 |

| MI | 23 (16.4%) | 205 (7.0%) | 2.56 (1.66–3.94) | <0.0001 |

| Death or MI | 38 (26.2%) | 370 (12.1%) | 2.34 (1.67–3.26) | <0.0001 |

| Ischemic TVR | 34 (24.2%) | 414 (14.0%) | 1.90 (1.34–2.70) | 0.0003 |

| Definite/probable stent thrombosis | 13 (10.2%) | 139 (4.8%) | 2.22 (1.26–3.91) | 0.005 |

| Stroke | 8 (5.8%) | 143 (1.5%) | 4.07 (1.91–8.66) | <0.0001 |

| Ischemic | 8 (5.8%) | 39 (1.3%) | 4.49 (2.10–9.60) | <0.0001 |

| Hemorrhagic | 0 (0%) | 4 (0.1%) | — | 0.67 |

| Major bleeding (non-CABG-related) | 30 (20.9%) | 251 (8.2%) | 2.67 (1.83–3.89) | <0.0001 |

| Variable | New-Onset AF, DES (Paclitaxel) (n = 85) | No New-Onset AF, DES (Paclitaxel) (n = 2,133) | p Value | New-Onset AF, BMS (n = 44) | No New-Onset AF, BMS (n = 804) | p Value | p Value ∗ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 days | |||||||

| Definite ST | 3 (3.5%) | 40 (1.9%) | 0.27 | 2 (4.5%) | 15 (1.9%) | 0.21 | 0.78 |

| Definite/probable ST | 4 (4.7%) | 45 (2.1%) | 0.10 | 2 (4.5%) | 18 (2.3%) | 0.32 | 0.96 |

| 1 yr | |||||||

| Definite ST | 6 (7.3%) | 58 (2.8%) | 0.02 | 3 (7.0%) | 19 (2.4%) | 0.07 | 0.95 |

| Definite/probable ST | 7 (8.4%) | 65 (3.1%) | 0.007 | 4 (9.3%) | 22 (2.8%) | 0.02 | 0.89 |

| 3 yrs | |||||||

| Definite ST | 6 (7.3%) | 91 (4.4%) | 0.19 | 5 (12.1%) | 28 (3.6%) | 0.007 | 0.44 |

| Definite/probable ST | 7 (8.4%) | 100 (4.9%) | 0.12 | 6 (14.2%) | 33 (4.3%) | 0.003 | 0.37 |

∗ Between new-onset AF with DES (paclitaxel) and new-onset AF with BMS.

The only identifiable predictors of occurrence of new-onset AF after PCI were age (hazard ratio [HR] 1.75, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.50 to 2.05, p <0.0001) and body mass index (HR 1.04, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.08, p = 0.02). New-onset AF was shown to be a strong independent predictor of NACEs (HR 1.74, 95% CI 1.30 to 2.34, p = 0.0002) and MACEs (HR 1.73, 95% CI 1.27 to 2.36, p = 0.0005), with a nonsignificant trend for all-cause death (HR 1.51, 95% CI 0.91 to 2.50, p = 0.11) at 3 years ( Table 4 ).