Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias Other Than Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

INTRODUCTION

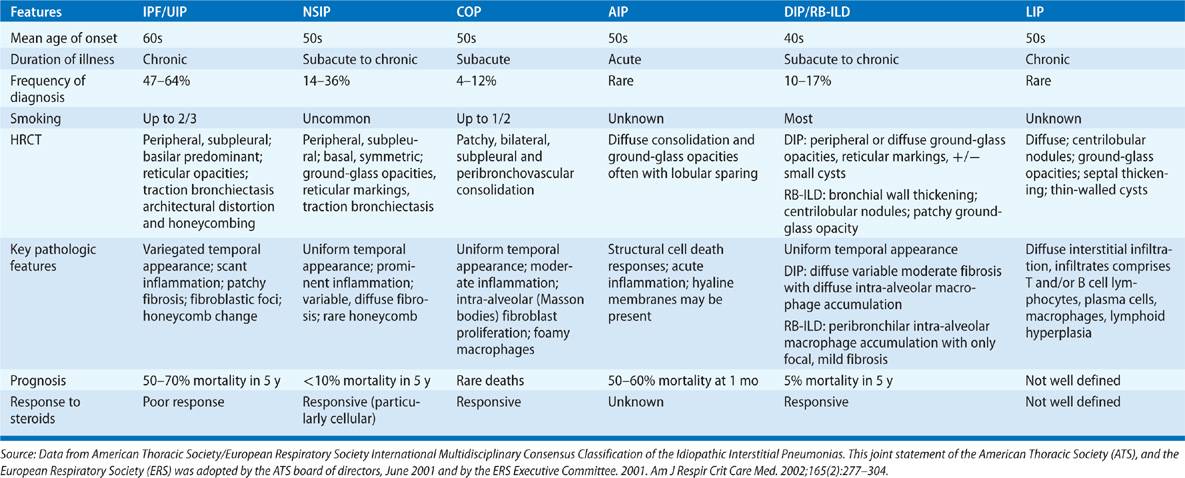

The idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs) encompass a subcategory of interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) that pose significant diagnostic and management challenges. The general diagnostic approach to these disorders is discussed elsewhere in this textbook (Chapter 54), as is the diagnosis and management of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), (Chapter 56). This chapter details the classification, diagnosis, and management of non-IPF forms of IIPs including nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), organizing pneumonia (OP), desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP), and respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease (RB-ILD), acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP), and lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP). Historical perspectives, current definitions, and epidemiologic information will be provided along with clinical aspects, imaging, and pathologic findings. Each section ends with a discussion of current therapeutic options. This information is summarized in Table 57-1.

NONSPECIFIC INTERSTITIAL PNEUMONIA

The important entity of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia is discussed below.

DEFINITION AND HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

DEFINITION AND HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

In 1994, the term “nonspecific interstitial pneumonia” (NSIP) was developed by Katzenstein and Fiorelli1 to describe a histologic pattern that demonstrates a temporally uniform appearance of interstitial inflammation and fibrosis This definition was further refined in 1998, when Katzenstein went on to formally designate NSIP as a distinct category within the IIPs.2 While most sources are in agreement about the presence of NSIP as a distinct histologic entity, the existence of NSIP as a distinct clinical entity remains controversial.3–5 For example, the American Thoracic Society (ATS) reports that in one review of 193 cases of NSIP, only 67 cases (or approximately one-third) were truly idiopathic while the rest were associated with a discrete diagnosis. As a result, when a radiographic or pathologic diagnosis of NSIP is made, clinicians should search for one of the underlying conditions with which this pattern is known to be associated.

UNDERLYING DISEASE ASSOCIATIONS

UNDERLYING DISEASE ASSOCIATIONS

Nonidiopathic NSIP is associated with a number of underlying causes.5,6 NSIP is the most prevalent form of ILD to complicate connective tissue diseases (CTD) and as such is frequently the histologic pattern seen when ILD complicates polymyositis and dermatomyositis,7 Sjögren syndrome,8 and systemic sclerosis (SSc).9 NSIP is seen in rheumatoid arthritis though far less commonly than is usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP).10 NSIP is also encountered in the setting of hypersensitivity pneumonitis,11 drug reactions,12 and in some forms of familial ILD.13 Some cases of apparently idiopathic NSIP may later develop CTD, indicating that NSIP is a forme fruste of CTD.14

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

NSIP most commonly affects nonsmoking middle-aged adults between 40 and 60 years of age and has a female predilection.1,4,15 Like most other IIPs, NSIP tends to present with the subacute onset of dyspnea and cough. Lung examination frequently reveals bilateral crackles though in some settings lungs will be clear. Extrapulmonary examination may provide clues to an underlying CTD (Chapter 60). For example, the presence of a heliotrope rash, shawl-like rash, and digital edema/desquamation (the so-called “mechanic’s hands”) suggests underlying dermatomyositis. The presence of telangiectasis, calcinosis, and sclerodactyly suggests a diagnosis of scleroderma. The presence of joint effusions and radial deviation of the MCP joints suggests an underlying diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Clubbing is seen only rarely.

Patients sometimes present without an established diagnosis. In this case, a complete history regarding occupational, environmental, and medication exposures must be obtained. In addition, because idiopathic NSIP is frequently associated with CTD, an exhaustive rheumatologic history should be obtained. This includes questions regarding the presence of arthralgias, swallowing difficulties, myopathic symptoms, rash and mechanic’s hands commonly encountered in antisynthetase syndrome, ocular and/or salivary gland dryness associated with Sjögren syndrome, and Raynaud phenomenon and swallowing difficulties that are characteristic of SSc. While most sources recommend serologic testing in the diagnosis of NSIP, there exist no standardized practice guidelines in this area. At minimum, ANA and rheumatoid factor should be ordered, along with extractable nuclear antigens (which include Jo-1 and Scl-70) and anticyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP). Serum creatine phosphokinase (CPK) and aldolase are useful in the diagnosis of myositis. Because hypersensitivity pneumonitis may also present with NSIP, antigen testing for mold or birds is sometimes performed though the clinical relevance of a positive (or negative) test is unclear and as such these tests are insufficient for diagnostic purposes.

PULMONARY FUNCTION TESTING

PULMONARY FUNCTION TESTING

Pulmonary function testing demonstrates a restrictive ventilatory defect characterized by a preserved FEV1/FVC ratio and a depressed FVC, TLC, and DLCO. The presence of obstructive physiology should raise suspicion of an alternate or superimposed diagnosis.

CHEST IMAGING

CHEST IMAGING

The imaging appearance of NSIP may vary, depending on if it is cellular, fibrotic, or mixed. Chest radiograph may be normal in patients with early disease or show nonspecific interstitial markings and ground-glass opacities mostly in the lower lobes with more advanced disease. Distribution of disease at CT is typically peripheral and lower lobe predominant, but may also involve the upper lobes without an obvious apicobasal gradient and can be patchy or peribronchovascular in distribution as well.16–19 The most common CT findings include ground-glass density and reticular markings with or without traction bronchiectasis (Figs. 57-1 and 57-2). Honeycombing is sometimes seen in fibrotic NSIP but is usually not the dominant feature.18,19

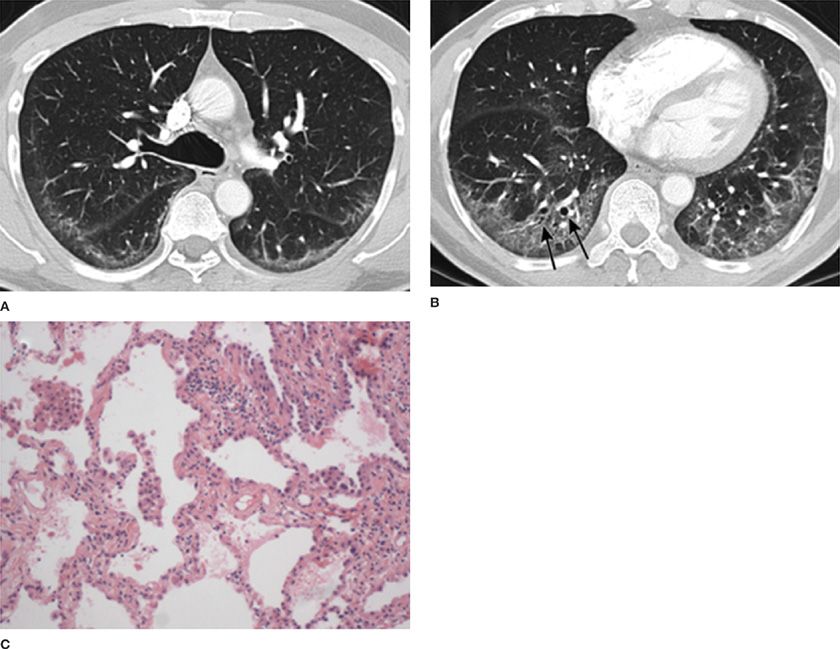

Figure 57-1 A 60-year-old male with antisynthetase syndrome and cellular nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP). High-resolution CT images through the upper (A) and lower (B) thorax demonstrate peripheral and lower lobe predominant ground-glass opacities with mild reticular markings and minimal traction bronchiectasis (arrows). C. Open lung biopsy revealed temporally uniform septal thickening and inflammation consistent with a cellular NSIP. (Pathology images used with permission of Robert J. Homer, MD, PhD, Yale School of Medicine.)

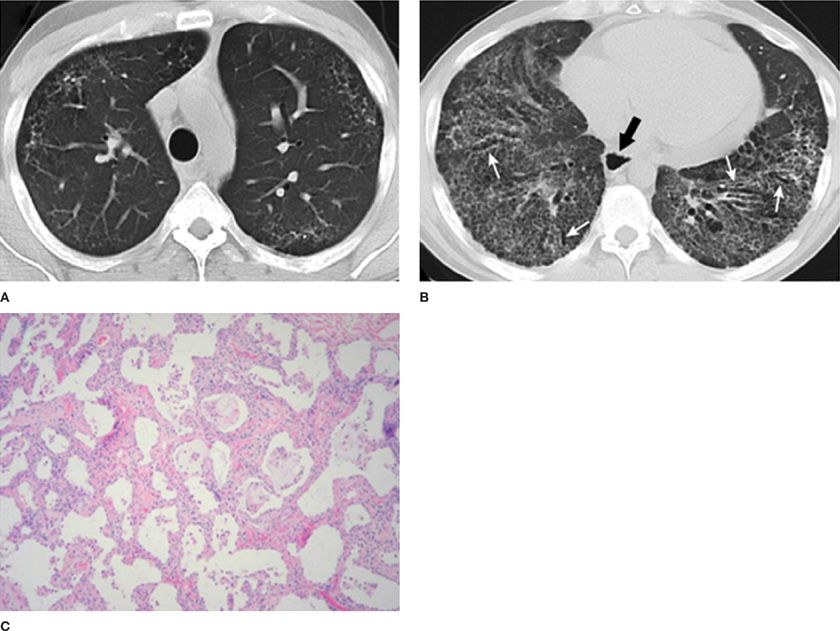

Figure 57-2 A 41-year-old male with fibrotic NSIP secondary to scleroderma. Axial CT images through the upper (A) and lower (B) thorax demonstrate extensive lower lobe predominant fibrotic changes with coarse reticular markings and traction bronchiectasis (white arrows). Note also the presence of a dilated esophagus (black arrow). The constellation of findings is compatible with a fibrotic NSIP pattern secondary to scleroderma. C. This patient eventually underwent lung transplantation and pathologic examination of the explanted lung revealed diffuse septal thickening and fibrosis with little inflammation, consistent with fibrotic NSIP. (Pathology images used with permission of Robert J. Homer, MD, PhD, Yale School of Medicine.)

PATHOLOGY

PATHOLOGY

When a tissue biopsy is required for diagnosis of NSIP, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) is the procedure of choice because this approach yields sufficient tissue to accurately diagnose the IIPs. The original description of NSIP categorizes its temporally uniform appearance of fibrosis and inflammation into three groups: those dominated by active inflammation (later called, “cellular” NSIP [Fig. 57-1]), those dominated by established fibrosis (later called, “fibrotic” NSIP [Fig. 57-2]), and those demonstrating a combination of inflammation and fibrosis (later called, “mixed” NSIP.1)

CLINICAL COURSE, OUTCOME, AND TREATMENT

CLINICAL COURSE, OUTCOME, AND TREATMENT

Patients with NSIP demonstrate a good to fair prognosis as shown by several studies. Those individuals with cellular NSIP can expect 74% survival at 5 years20 and this specific pathologic pattern is associated with reduced event-free survival compared to the fibrotic forms.21 Similarly, radiographic changes that would be expected to accompany fibrotic NSIP such as honeycombing have been associated with reduced survival, as have progressive dyspnea and desaturation during 6-minute walk test.20

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Immunosuppression is commonly employed in the management of NSIP but the lack of prospective, randomized controlled trials in this area means that evidence for a therapeutic effect of these agents is lacking. For cases of exposure-related NSIP related to drugs or inhalations, cessation of the offending agent is the initial treatment strategy. In very mild situations this intervention may be sufficient but oftentimes patients with significant disease burden radiographically or physiologically require treatment with systemically administered immunosuppressive agents. Patients with arterial hypoxemia at rest or during exercise require the administration of supplemental oxygen. Patients with exercise impairment may benefit from pulmonary rehabilitation. Finally, due to the rapid deterioration that is sometimes encountered in patients with NSIP, referral for orthotopic lung transplantation (OLT) should be considered for any eligible patient.

The use of immunosuppression is based on the rationale that the inflammation seen on pathology at least partially contributes to disease. Most of the immunosuppressive agents used to treat NSIP have not been formally evaluated in prospective, randomized clinical trials and all of them have significant toxicities. Thus, the decision to embark upon a course of immunosuppression should be considered in light of the risk–benefit ratio. Similarly, when treating a patient with NSIP in the setting of CTD, the management of these medications is best performed with the patient’s rheumatologist because since the pulmonary and systemic involvement may demonstrate independent responses, systemic effects must be monitored as well. Patients should be seen frequently and should have lab monitored monthly in order that serious and potentially fatal side effects can be recognized in a timely fashion.

Corticosteroids

Despite a lack of clinical trials in this area, expert opinion recommends a trial of corticosteroid therapy in patients with NSIP. Patients are typically treated with 1 mg/kg per ideal body weight of oral prednisone for several months and then assessed for evidence of objective response on PFTs or HRCT.16 The side effects of steroid therapy are well-known and include diabetes, bone complications, cataracts, hypertension, weight gain, and opportunistic infection so patients should be followed closely with serial monitoring blood chemistry and CBC. Due to these toxicities, every attempt to transition the patient to a steroid-sparing agent is made once the patient has responded to therapy.

Azathioprine

Azathioprine is a commonly used alternate therapy used in patients with NSIP. The evidence for this approach derives from an early study of subjects with IIPs in which a small subset comprised in part of patients with NSIP were found to improve. There have since then been no large-scale clinical trials in this area though one small case series found that patients with fibrotic NSIP experienced improved outcomes when treated with combination therapy of prednisone and azathioprine.20 Because azathioprine carries several risks including bone-marrow suppression and hepatotoxicity most centers perform genotyping for thiopurine methyltransferase prior to initiation of therapy and when a mutation is uncovered reduce dosage accordingly though evidence for this approach is currently lacking.

Cyclophosphamide

Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan™) is used in patients with significant or rapidly progressive lung involvement. In a prospective study comparing patients with confirmed fibrotic NSIP versus those with UIP/IPF receiving pulse therapy with methylprednisolone followed by low-dose prednisone and cyclophosphamide, 33% of subjects with NSIP improved with steroids alone and 66% improved with combined therapy. In contrast, only 15% of the subjects with UIP/IPF demonstrated clinical improvement at either timepoint.22 Further suggestion of efficacy was provided by a small retrospective study in which patients with known or suspected NSIP showed stabilization of lung function following 6 months of therapy. Perhaps the best evidence for a therapeutic benefit of Cytoxan™ was seen in patients with SSc-ILD (most of whom have NSIP) randomized to placebo or Cytoxan™. A small but significant improvement in lung function was noted in those subjects assigned to the treatment arm23 though subsequent analysis found this effect to dissipate after 2 years.24 Because cyclophosphamide is associated with many side effects including bone-marrow suppression, hemorrhagic cystitis, and the long-term risk of bladder cancer and hematologic malignancies, its use is reserved for severe and progressive cases of NSIP and it is recommended that it only be used by experienced practitioners with appropriate monitoring.

Other Immunosuppressive Agents

Several case series indicate that mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) may be efficacious in delaying lung function decline in patients with SSc-ILD.25,26 Because most of these patients have NSIP, these studies are viewed as providing direct evidence of a potential role for MMF in the management of this form of ILD. A large-scale randomized controlled trial of MMF versus cyclophosphamide is currently underway in for the treatment of SSc-ILD. MMF is started at 500 mg b.i.d. and titrated up to a maximum dosage of 2000 mg b.i.d. This agent is pregnancy category D due to its teratogenic potential. A role for tacrolimus in the treatment of NSIP is supported by one retrospective series27 of patients with polymyositis- and dermatomyositis-related ILD. However, because no large-scale studies have been performed, consideration of this agent for the treatment of NSIP should be considered on a case-by-case basis and patients should be managed with physicians who are experienced in the interpretation of serum levels. The most feared side effect is renal toxicity, which can in some cases be permanent and lead to kidney failure.

CRYPTOGENIC ORGANIZING PNEUMONIA

The entity of cryptogenic organizing pneumonia was described over 30 years ago. Important clinical aspects and associations are described below.

DEFINITION AND HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

DEFINITION AND HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

First described by Davison28 and Epler29 in the early 1980s, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP) was categorized as an IIP in a 2002 working group sponsored by the ATS and the European Respiratory Society (ERS).16 The pathologic hallmark of COP consists of whorls of myofibroblasts and inflammatory cells in a connective tissue matrix within the distal airspaces. This nonspecific pathologic pattern is termed “organizing pneumonia” and is found in a variety of settings such as in the context of infection, drug toxicity, posttransplant, radiation exposure, or rheumatologic conditions. Therefore, it is only in the absence of an associated condition or inciting factor that clinicians may establish a diagnosis of COP. Thus, the diagnosis of COP rests on an integrated assessment of clinical symptoms, radiographic patterns, compatible histopathologic features, when available, and the exclusion of other associated causes and conditions.

The pathology was initially called “bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia” (BOOP) and this term initially dominated the North American literature and was included in the seminal paper by Katzenstein and Myers in 1998.30 Given clinical confusion between the term BOOP and the distinct airway-centered disease of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (“BOS”), the terminology was changed in 2002. However, because many cases of COP are associated with an underlying etiology, the inclusion of COP as an “idiopathic” interstitial pneumonia has also been confusing for some. Perhaps most perplexing to clinicians is the fact that the disease in COP dominates the airspaces and not the interstitium. However, the working group justified the inclusion of COP within the IIPs because in clinical practice COP is part of the differential diagnosis of other IIPs, and because interstitial inflammation and fibrosis may be present in COP.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Similar to other IIPs, the epidemiology of COP is not well characterized though it seems to affect both genders equally with a mean age of onset of 58 years. Nonsmokers or former smokers may be affected more frequently than current smokers.31 The classic presentation of COP includes an initial prodromal flu-like illness and symptoms of fever, cough, and dyspnea. Complaints such as hemoptysis, chest pain, arthralgias, or myalgias are uncommon. Chest auscultation may be clear or may reveal crackles. Patients are frequently treated with multiple courses of antibiotics before being diagnosed. The presence of systemic symptoms and/or findings consistent with CTD should lead to careful investigation for an associated underlying disease.32

UNDERLYING ASSOCIATIONS

UNDERLYING ASSOCIATIONS

A diagnosis of COP requires exclusion of associated causes. It has been suggested that gastroesophageal reflux with silent aspiration may play a role in the development of OP; however, this association has not been firmly established.33 Many viral, bacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections have been implicated31,34 as has influenza A H1N1 flu.35 OP is a frequently encountered manifestation of drug-induced lung disease caused by antibiotics such as nitrofurantoin, medications such as phenytoin, amiodarone, sulfasalazine,36 and illicit drugs such as cocaine.37 Occupational exposures are also associated with an OP pattern of lung injury including but not limited to the aerosolized textile dye Acramin FWN, titanium nanoparticles in paint, and certain chemicals used in spice processing.38–40 OP has been reported in patients with dermatomyositis-polymyositis41–46 as well as other conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis,47–49 scleroderma,50–52 and systemic lupus erythematosus.53–55 Rheumatologic serologies can be helpful in identifying the presence of disease because this form of lung injury may present as the initial manifestation of systemic disease. OP may be present in other inflammatory diseases such as in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.56 Radiotherapy treatment is also associated with the development of OP particularly after treatment for breast cancer 3 to 6 months following therapy. Compared to radiation pneumonitis which is fairly well circumscribed and characterized by retracted lung and traction bronchiectasis, postradiotherapy OP occurs diffusely, is migratory, and is highly steroid responsive.57 OP can also occur following transplantation of lung or bone marrow. While BOS is the most commonly reported lung injury pattern in patients experiencing lung transplant rejection, OP patterns have also been described.58,59 Similarly, bone-marrow transplant recipients may develop OP as a manifestation of transplant rejection, graft-versus-host disease, or idiopathic pneumonia syndrome.60–62 OP can also complicate malignant or hematologic conditions such as various forms of acute and chronic leukemias and lymphomas.63

PULMONARY FUNCTION TESTING

PULMONARY FUNCTION TESTING

Similar to other IIPs, a restrictive ventilatory defect, characterized by a reduction in total lung capacity is generally present. In a subset of patients, an obstructive ventilatory defect can be found. Hypoxemia is typically mild although in a subgroup of patients with infiltrative opacities severe hypoxemia may be seen.64,65

CHEST IMAGING

CHEST IMAGING

OP displays a variable imaging appearance. The CXR usually shows nonspecific patchy areas of consolidation. Sometimes the imaging appearance mimics infectious pneumonia with lobar consolidation that is unresponsive to antibiotics. Peripheral, patchy, and peribronchovascular areas of ground-glass opacity and consolidation are the most classic CT appearance (Fig. 57-3).16,17,66 Nodular areas of ground glass and consolidation as well as fleeting or migratory areas of consolidation can also be seen with OP.16,17,66 Findings suggestive of fibrosis such as reticulation, architectural distortion, traction bronchiectasis, and honeycombing are not typically present with this entity. An area of ground-glass opacity surrounded by a rim of increased density, also known as the atoll (or reverse-halo) sign, when present, is strongly suggestive of OP66 but can also be present with other entities such as vasculitis, certain infections, or pulmonary infarction.

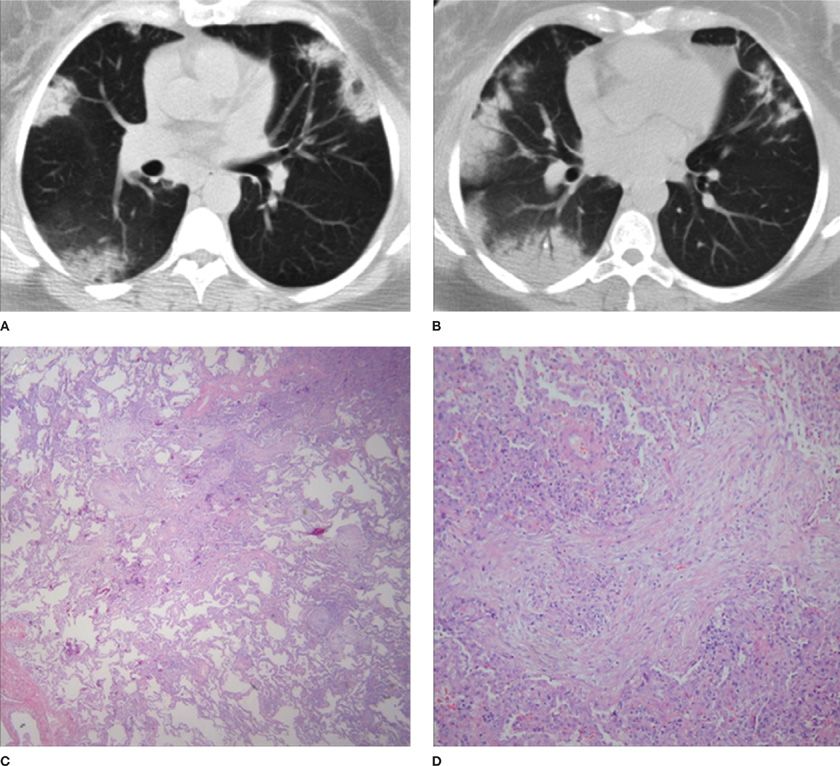

Figure 57-3 A 50-year-old female with cough and dyspnea secondary to organizing pneumonia (OP). Axial CT images through the mid (A) and mid to lower (B) thorax demonstrate multifocal, peripheral areas of consolidation with a distribution compatible with OP. Low (C) and high (D) power views of lung tissue from this patient reveal a patchy organizing pneumonia pattern of exudates, fibroblasts, and inflammatory cells. (Pathology images used with permission of Robert J. Homer, MD, PhD, Yale School of Medicine.)

PATHOLOGY

PATHOLOGY

When the clinical presentation and chest imaging is insufficient for a confident diagnosis of COP, bronchoscopy with transbronchial biopsy or surgical lung biopsy can be employed. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) typically reveals significant accumulation of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils. Transbronchial biopsies may be performed to make a diagnosis; however, the quantity of lung tissue obtained during these procedures is quite small and may be insufficient to fully evaluate the spectrum of pathology that may exist within the lung parenchyma.67–69 Thus, larger lung tissue specimens obtained by VATS are frequently used to provide the opportunity for more thorough analyses.

The pathology of OP is characterized by intraluminal plugs of inflammatory debris within the alveolar ducts and surrounding alveoli. The plugs consist of buds of granulation tissue, whorls of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in a connective tissue matrix referred to as Masson bodies (Fig. 57-3). OP patterns can be seen concomitantly in patients with NSIP or UIP and may in certain patients represent an exacerbation of underlying ILD. In this setting, interpretation of the pathology in the context of the radiographic and clinical features can greatly aid in accurate diagnosis.

CLINICAL COURSE, OUTCOME, AND TREATMENT

CLINICAL COURSE, OUTCOME, AND TREATMENT

Patients with mild or asymptomatic disease may not require treatment.70 When compared to other fibrotic lung diseases such as IPF, COP is impressively steroid responsive though a significant proportion of patients, ranging from 13% to 58%, experience relapse. Fortunately, relapses are not associated with poorer long-term outcomes and death is very infrequent.

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Historically, a 6-month course of treatment has been advised. More recently, shorter 3-month durations of corticosteroids have been recommended to avoid unnecessarily prolonged courses of steroids in patients who do not relapse.32 Macrolide antibiotics71 and steroid-sparing agents72,73 have been used as alternative immunosuppressants for individuals with COP or secondary OP. However, the clinical utility of these approaches has not been completely validated. It is not known whether individuals with secondary causes of OP experience different long-term outcomes from individuals with COP.

While the majority of COP patients have favorable prognosis, a subset of patients present with a rapidly progressive and fatal form of OP. Some investigators have suggested that such cases represent an overlap group with acute interstitial pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). In another series, AFOP, an acute fibrinous organizing pneumonia pattern was reported. In AFOP, organizing pneumonia and intra-alveolar fibrin balls are present.74 Nonetheless, the literature does suggest that a small subgroup of COP patients suffer a progressive fibrotic course. Alternative forms of immunosuppression such as cyclophosphamide have been used in such rapidly deteriorating patients though experience with this approach is at best limited and the clinical utility is not entirely clear.72

RESPIRATORY BRONCHIOLITIS-ASSOCIATED INTERSTITIAL LUNG DISEASE AND DESQUAMATIVE INTERSTITIAL PNEUMONIA

The entities of respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease and desquamative interstitial pneumonia are part of a spectrum of disorders affecting smokers. Important clinical and pathologic considerations in these two entities are described below.

DEFINITION AND HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

DEFINITION AND HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

While regarded clinically as two discrete forms of IIPs, RB-ILD and DIP are generally thought of as representing ends of a continuous spectrum of disease primarily affecting tobacco smokers. The diagnostic distinction persists due to evidence indicating that RB-ILD and DIP have divergent natural histories and prognoses. The pathologic hallmark of both diseases features cytoplasmic accumulation of golden-brown pigment in macrophages. RB-ILD pathology appears to reflect inhalational exposure as findings center around the bronchioles with peribronchiolar inflammation and fibrosis. In contrast, DIP involves the airways but also extends into the alveolar space and may even include mild to moderate associated interstitial fibrosis. Because RB-ILD and DIP reactions are frequent and often incidental findings in the lung tissue of smokers, formal clinical diagnosis of RB-ILD or DIP hinges upon the presence of symptomatic, radiographic, and functional impairment. Taken together, DIP and RB-ILD account for up to 15% to 20% of patients with biopsied IIPs.75–78

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Patients diagnosed with RB-ILD and DIP are typically males in the fourth or fifth decade of life with an average 30 pack-year smoking history. Affected patients report nonspecific complaints of progressive dyspnea and nonproductive cough. Physical examination may be normal but might reveal dry inspiratory crackles and clubbing as seen in other forms of ILDs. Extrapulmonary findings are usually absent.

UNDERLYING ASSOCIATIONS

UNDERLYING ASSOCIATIONS

Tobacco smoke exposure accounts for the most cases of RB-ILD and DIP, despite their categorization as “IIPs.” In fact, it has been reported that up to 90% of RB-ILD and DIP cases are causatively linked to tobacco smoke.75 However, in one review of 49 cases, it was noted that only 60% of DIP patients versus 93% of RB-ILD patients had a prior smoking history.79 Although the lower prevalence of smoking in this study compared to prior studies may reflect referral bias, investigators should remain cognizant that such pathologies can occur independently of smoking. When viewed in this light, it is relevant that a number of exposures have been reported in association with DIP such as marijuana smoking, diesel fume, beryllium, copper, fire extinguisher powder, asbestos, and certain chemicals used to process textiles.79–82 DIP has also been reported as a complication of autoimmune disorders including rheumatoid arthritis and scleroderma50,52,80,83 and has occurred in association with infections such as hepatitis C, cytomegalovirus, and aspergillus.84–86 Finally, idiopathic DIP has also been reported.79 Genetic factors seem unlikely to play a dominant role; however, a few studies particularly among children and sibling studies have implicated genetic abnormalities of surfactant function, such as mutations in SP-B, SP-C, and ABCA-3 genes87–89 though the applicability of these studies to the adult IIPs described herein remain uncertain. The difficulty in determining the contribution of other exposures may occur because when evaluating individuals with a smoking history, clinical providers dismiss the possible contribution of alternate etiologies. Furthermore, since many individuals with conditions such as rheumatologic disease do not proceed to lung biopsy, the specific underlying pathology of the associated IIP may remain unconfirmed and individuals may be assumed to have NSIP.

PULMONARY FUNCTION TESTING

PULMONARY FUNCTION TESTING

Patients with RB-ILD often manifest a restrictive physiologic pattern with concomitant reduction in DLCO

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree