Anatomy and pathology are 2 of medicine’s oldest and most distinguished disciplines. Jesse Edwards, who founded cardiac pathology at the Mayo Clinic, and William C. Roberts, first head of pathology at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, are in the best tradition as reflected in this manuscript.

Leonardo da Vinci was the illegitimate son of a beautiful peasant girl, Caterina, and a local notary, Piero da Vinci. Leonardo was born in a small Tuscan hill town, where he lived until his father arranged for him to study in Florence at Compagnia di San Luca, a painter’s guild at the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova ( Figure 1 ), which included physicians and apothecaries.

The scientific achievements of Leonardo da Vinci, genius of the Renaissance ( Figure 2 ), were virtually unknown during his lifetime and remained unknown for more than 2 centuries after his death. Between 1489 and 1513 in the crypt of Santa Maria Nuova, Leonardo dissected more than 30 bodies of both genders and all ages. Dissections were a messy business, demanding resilience to withstand the odious sights and awful odors of decomposing corpses. Leonardo performed his dissections at night by candlelight, which made them even more macabre. He paid grave robbers to bring him bodies for his anatomic and pathologic studies. Body snatching was illegal, but the law was not enforced.

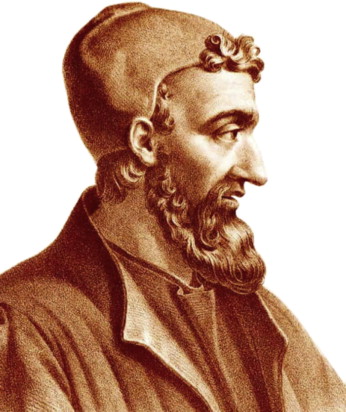

Galen ( Figure 3 ), anatomist, physician, and philosopher ( ad 130–200), dissected Barbary apes because the Church forbade human postmortem dissection, although Christian theology did not regard the human cadaver as sacrosanct. Human dissection was forbidden in the Roman Empire (753 bc to ad 476).

Leonardo was sensitive to human dignity, as illustrated by the postmortem of an aged man who died in his presence : “And this old man, a few hours before his death, told me he was over a hundred years old and that he felt nothing wrong with his body other than weakness. And thus, while sitting on his bed in the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova, without any movement or other sign of mishap, he passed out of this life. And I made an anatomy of him in order to see the cause of so sweet a death.”

In late 13th-century and early 14th-century Europe, dissection of the bodies of executed criminals was legalized, and in the 16th century, physicians and surgeons in England were given limited rights to dissect cadavers. The Murder Act of 1752 added terror and infamy to punishment by authorizing dissection of the bodies of criminals. The Company of Barber-Surgeons and the Royal College of Physicians were authorized to perform dissections. The iconic red and white striped pole symbolizing blood and bandages is the last vestige of the Barber-Surgeons.

Few physicians today have read or even heard of Leonardo’s description of the circumstances under which he worked: “There were no chemicals to preserve the cadavers which began to decompose before there was time to examine and draw them properly. You will perhaps be impeded by your stomach, and if this does not impede you, you will perhaps be impeded by the fear of living through the night hours in the company of these corpses, quartered and flayed and frightening to behold. One single body was not sufficient, so it was necessary to proceed little by little with as many bodies as would render the complete knowledge.”

Despite the adverse circumstances, Leonardo carried out his dissections with patience, delicacy, and meticulous attention to detail. Minute particles of flesh and muscle were meticulously teased away to expose small blood vessels until the corpse was too dismembered to permit further dissection. Among Leonardo’s many gifts was complete visual recall. Once he saw an object, he could draw it precisely, and he did so after each of his dissections.

Leonardo was in awe of the beauty of natural forms and nature’s ingenuity, which he regarded as far superior to human design, but his depiction of the human fetus in its intrauterine position is beautiful ( Figure 4 ).