Congenital heart disease (CHD) is common in patients with Down syndrome (DS), and these patients are living longer lives. The aim of this study was to describe the epidemiology of hospitalizations in adults with DS and CHD in the United States. Hospitalizations from 1998 to 2009 for adults aged 18 to 64 years with and without DS with CHD diagnoses associated with DS (atrioventricular canal defect, ventricular septal defect, tetralogy of Fallot, and patent ductus arteriosus) were analyzed using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Outcomes of interest were (1) in-hospital mortality, (2) common co-morbidities, (3) cardiac procedures, (4) hospital charges, and (5) length of stay. Multivariate modeling adjusted for age, gender, CHD diagnosis, and co-morbidities. There were 78,793 ± 2,653 CHD admissions, 9,088 ± 351 (11.5%) of which were associated with diagnoses of DS. The proportion of admissions associated with DS (DS/CHD) decreased from 15.2 ± 1.3% to 8.5 ± 0.9%. DS was associated with higher in-hospital mortality (odds ratio [OR] 1.8, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.4 to 2.4), especially in women (OR 2.4, 95% CI 1.7 to 3.4). DS/CHD admissions were more commonly associated with hypothyroidism (OR 7.7, 95% CI 6.6 to 9.0), dementia (OR 82.0, 95% CI 32 to 213), heart failure (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.9 to 2.5), pulmonary hypertension (OR 2.5, 95% CI 2.2 to 2.9), and cyanosis or secondary polycythemia (OR 4.6, 95% CI 3.8 to 5.6). Conversely, DS/CHD hospitalizations were less likely to include cardiac procedures or surgery (OR 0.3, 95% CI 0.2 to 0.4) and were associated with lower charges ($23,789 ± $1,177 vs $39,464 ± $1,371, p <0.0001) compared to non-DS/CHD admissions. In conclusion, DS/CHD hospitalizations represent a decreasing proportion of admissions for adults with CHD typical of DS; patients with DS/CHD are more likely to die during hospitalization but less likely to undergo a cardiac procedure.

The incidence of Down syndrome (DS), the most common chromosomal abnormality, has remained stable over time in the setting of higher prenatal detection rates and increasing average maternal age. Life expectancy for DS has improved in the United States, with the median age at death almost doubling from 25 to 49 years from 1983 to 1997. DS is frequently associated with congenital heart disease (CHD). With a stable annual number of DS births and improving survival, one might expect an increasing population of adults with DS and CHD. This would be an especially important trend among older patients with DS and CHD, who may have specific requirements influenced by CHD and by notable cognitive and physical co-morbidities. Although children with DS and CHD are reported to use 10 times more medical care compared to those with DS alone, there are few reports concerning adult patients with DS with CHD and the health care resources used by this population.

Methods

We performed a retrospective, cross-sectional, observational study using administrative hospitalization data for adults aged 18 to 64 years with or without DS hospitalized for any reason with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), diagnosis codes for CHD diagnoses associated with DS (758.0) : atrioventricular canal or endocardial cushion defect (745.6), ventricular septal defect (745.4), tetralogy of Fallot (745.2), and patent ductus arteriosus (747.0). Hospitalizations without ≥1 of these diagnoses were excluded. Data were extracted from the 1998 to 2009 Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), the largest publicly available all-payer inpatient care database in the United States. The NIS includes data on approximately 7 million to 8 million discharges annually. Hospitals included in the NIS represent a stratified sample designed to approximate a 20% sample of United States nonfederal, short-term, general and specialty hospitals. Demographic covariates collected included age in years, gender, and year of admission.

Cardiac co-morbidities were defined by ICD-9 diagnosis codes: arrhythmia (427.0, 427.1, 427.31, 427.32, 427.60, 427.81, 427.89, or 427.9), coronary artery disease (410 to 414), heart failure (428), pulmonary hypertension (416.0, 416.8, or 416.9), and syncope (780.2). Cyanosis (782.5) and “secondary polycythemia” (289.0) were combined into a single variable, as they would be expected to represent equivalent underlying pathophysiology.

Cardiac procedures were defined by the following ICD-9 procedure codes: cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass (39.61, 39.62, 39.63, 39.65, or 39.66), electrophysiology study (37.26 or 37.27), pacemaker insertion or revision (37.7 or 37.8), percutaneous ablation procedure (37.34), percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (00.66), and right-sided and/or left-sided cardiac catheterization (37.21 to 37.23). We also defined a dichotomous variable designating whether a given hospitalization was associated with any 1 or more of these procedures (yes or no).

The following noncardiac co-morbidities were analyzed: acute renal failure (584), acute respiratory failure (518.81), aspiration pneumonia (507.0), dementia (290, 294.1, and 331.0), hypothyroidism (244 and 245), invasive mechanical ventilation (ICD-9 procedure code 96.7), leukemia (204 to 208), obesity (278), pneumonia (481 to 486), and seizure or convulsions (780.39). Common atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk factors analyzed were diabetes mellitus (250), systemic hypertension (401 to 405), and tobacco use (305.1 or v15.82). We also included a variable for pregnancy (as defined by the NIS) and the number of medical co-morbidities as described by Elixhauser et al.

To estimate health care resource utilization, we analyzed total hospital charges in dollars and length of stay in days. We repeated this analysis excluding patients who underwent cardiac surgery. We also evaluated teaching hospital status (yes or no) and primary type of insurance (Medicare, Medicaid, private, or self-pay or uninsured).

Primary outcomes of interest were the absolute number of DS admissions, the proportion of CHD admissions for patients with DS (DS/CHD), and in-hospital mortality. Secondary outcomes of interest were (1) the proportion of admissions with specified associated cardiac and noncardiac co-morbidities or events, (2) the proportion of admissions including ≥1 cardiac procedure, and (3) total hospital charges and length of stay per hospitalization. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models adjusting for these covariates were used to determine if DS was associated with the odds of in-hospital death or other outcomes. Likewise, logistic regression was used to determine the likelihood of cardiac and noncardiac co-morbidities and events. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS for Windows version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina). All analyses used provided sample weights and accounted for the complex sample design and clustering by hospital. The institutional review board of Boston Children’s Hospital granted an exemption to this study.

Results

There were 78,793 ± 2,653 hospital admissions for the specified CHD diagnoses from 1998 to 2009, of which 9,088 ± 351 (11.5%) were associated with diagnoses of DS. Demographic and clinical data of the 2 groups are listed in Table 1 .

| Variable | DS | No DS | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of admissions (weighted) | 9,088 ± 351 | 69,705 ± 2,302 | <0.0001 |

| Age (yrs) | 38.1 ± 0.4 | 38.5 ± 0.2 | 0.27 |

| Age group (yrs) | <0.0001 | ||

| 18–29 | 24.3 ± 1.5 | 31.4 ± 0.7 | |

| 30–39 | 29.8 ± 1.4 | 22.8 ± 0.5 | |

| 40–64 | 45.8 ± 0.8 | 45.8 ± 1.5 | |

| Women | 52.0 ± 1.6 | 58.8 ± 0.6 | <0.0001 |

| Pregnancy | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 12.0 ± 0.5 | <0.0001 |

| Type of congenital heart defect ∗ | <0.0001 | ||

| Atrioventricular canal defect | 19.3 ± 1.2 | 5.0 ± 0.3 | |

| Ventricular septal defect | 77.7 ± 1.2 | 67.9 ± 0.7 | |

| Tetralogy of Fallot | 9.0 ± 0.8 | 19.5 ± 0.6 | |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 10.1 ± 0.3 | |

| Teaching hospital admissions | 48.7 ± 2.0 | 63.9 ± 1.4 | <0.0001 |

| Primary type of insurance † | <0.0001 | ||

| Medicare | 65.6 ± 1.5 | 17.0 ± 0.5 | |

| Medicaid | 20.7 ± 1.3 | 22.7 ± 0.6 | |

| Private | 12.2 ± 1.0 | 48.9 ± 0.8 | |

| Self-pay/uninsured | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 6.6 ± 0.4 |

∗ Type of CHD sums to >100% because some hospitalizations included diagnostic codes for >1% CHD diagnosis.

† A small number of patients had other forms of insurance, and these are not included in this table.

The absolute number of DS/CHD hospitalizations decreased over the study period, while the number of hospitalizations with CHD without DS diagnoses increased ( Figure 1 ). As a result, the proportion of DS/CHD admissions decreased by about 44% during the study period (from 15.2% to 8.5%).

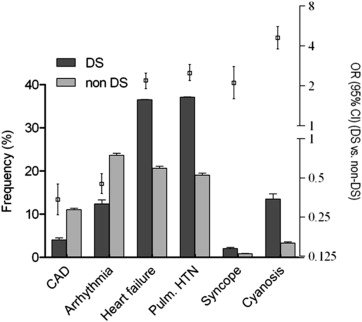

Certain cardiac co-morbid events and conditions were more common in those with DS than those without DS ( Figure 2 ). Most notably, those with DS had higher odds of heart failure (odds ratio [OR] 2.2, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.9 to 2.5), pulmonary hypertension (OR 2.5, 95% CI 2.2 to 2.9), and cyanosis (OR 4.6, 95% CI 3.8 to 5.6). Conversely, DS was associated with a lower likelihood of coronary artery disease (OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.45) and arrhythmia (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.54). DS admissions were also less commonly associated with coronary disease risk factors ( Figure 3 ). Regarding noncardiac co-morbidities and events, DS admissions were associated with significantly higher odds of leukemia (OR 4.6 95% CI 2.1 to 9.9), hypothyroidism (OR 7.7, 95% CI 6.6 to 9.0), and dementia (OR 82.0, 95% CI 32.0 to 213.6), among others shown in Figure 3 . There was no difference between groups in the odds for having acute renal failure (OR 1.1, 95% CI 0.8 to 1.4) or obesity (OR 1.2, 95% CI 0.9 to 1.4).

Death during hospitalization was more common among DS admissions ( Table 2 ). This was true for all age groups although most pronounced in younger patients. It also held true for men and women, but women with DS were at higher risk for death relative to women without DS than men were. Although patients with DS were less likely to undergo a cardiac procedure, the risk for mortality for patients with DS who underwent procedures was no different from that for patients without DS. For patients not undergoing procedures, DS was a strong risk factor for in-hospital mortality ( Table 2 ).

| Variable | DS | No DS | Univariate OR (95% CI) | Multivariate ∗ OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 7.9 ± 0.6 | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 2.5 (2.0–3.0) | 1.8 (1.4–2.4) |

| Age group (yrs) | ||||

| 18–29 | 6.7 ± 1.2 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 3.4 (2.2–5.2) | 2.1 (1.1–4.0) |

| 30–39 | 8.7 ± 1.2 | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 3.0 (2.1–4.3) | 2.7 (1.6–4.7) |

| 40–64 | 8.0 ± 0.9 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 1.9 (1.4–2.5) | 1.8 (1.3–2.7) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 6.1 ± 0.8 | 3.6 ± 0.3 | 1.8 (1.3–2.4) | 1.8 (1.2–2.8) |

| Female | 9.5 ± 0.9 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 3.2 (2.5–4.1) | 2.4 (1.7–3.5) |

| Cardiac procedure | ||||

| Yes | 3.1 ± 1.5 | 3.6 ± 0.3 | 0.9 (0.3–2.4) | 0.9 (0.3–3.0) |

| No | 8.2 ± 0.7 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 2.7 (2.2–3.3) | 2.2 (1.7–3.1) |

| Teaching hospital | ||||

| Yes | 7.6 ± 0.9 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 2.2 (1.7–2.9) | 1.8 (1.3–2.6) |

| No | 8.2 ± 0.9 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 2.9 (2.2–3.8) | 2.5 (1.6–3.8) |

∗ Multivariate analysis adjusted for age (except for age group analysis), cardiac procedure (except for cardiac procedure analysis), specified CHD diagnosis, specified procedures, hypothyroidism, leukemia, dementia, pneumonia, aspiration pneumonia, diabetes, invasive ventilation, acute renal failure, diabetes mellitus, number of Elixhauser co-morbidities, year of admission, gender, pregnancy, arrhythmia, polycythemia or cyanosis, heart failure, coronary artery disease, and pulmonary hypertension.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree