17 Home Care and Pulmonary Rehabilitation

Note 1: This book is written to cover every item listed as testable on the Entry Level Examination (ELE), Written Registry Examination (WRE), and Clinical Simulation Examination (CSE).

The listed code for each item is taken from the National Board for Respiratory Care’s (NBRC) Summary Content Outline for CRT (Certified Respiratory Therapist) and Written RRT (Registered Respiratory Therapist) Examinations (http://evolve.elsevier.com/Sills/resptherapist/). For example, if an item is testable on both the ELE and the WRE, it will simply be shown as: (Code: …). If an item is only testable on the ELE, it will be shown as: (ELE code: …). If an item is only testable on the WRE, it will be shown as: (WRE code: …).

MODULE A

1. Assess a patient’s learning needs (Code: IB6) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

It is very important to determine what the patient understands about his or her cardiopulmonary condition and its treatment. If the patient is found to need additional teaching in some area, it should be incorporated into the respiratory care plan. See Chapter 1 for more discussion on teaching methods.

2. Explain the planned therapy and goals to a patient in understandable terms to achieve optimal therapeutic outcomes (Code: IIIA6) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

3. Counsel a patient and family concerning smoking cessation (Code: IIIK6) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

MODULE B

1. Interview the patient to determine the presence of dyspnea, sputum production, and exercise tolerance (Code: IB5c) [Difficulty: ELE R, Ap; WRE: An]

c. Out-of-home activities

See Chapter 1 for the discussion on interviewing a patient about sputum production. The patient with chronic and severe cardiopulmonary disease may describe a very restricted and limited lifestyle. Extra O2 may have only limited benefit. The patient with chronic, but moderate, cardiopulmonary disease can live a somewhat limited but full lifestyle. Extra O2 may help greatly at times when the patient becomes short of breath. The otherwise healthy patient with an acute cardiopulmonary disease should describe a previously full and enjoyable lifestyle. Extra O2 may be needed now, but it is hoped that it will not be needed upon recovery.

2. Interview a patient to determine his or her social history (e.g., smoking, substance abuse) (Code: IB5e) [Difficulty: ELE: R; WRE: Ap]

The following questions can be asked of the family of a minor child:

3. Interview the patient to determine his or her nutritional status (ELE code: IB5d) [ELE difficulty: R]

4. Instruct the patient and family to assure safety and infection control (Code: IIIK7) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

Evaluate the following aspects of the patient’s home environment:

5. Home sleep apnea management

b. Interpret the results of overnight pulse oximetry (Code: IB10q) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

While it less expensive to perform overnight pulse oximetry in the home than polysomnography in the hospital, most patients who are suspected of having sleep-disordered breathing will be evaluated in the hospital. See the discussion on sleep-disordered breathing and overnight pulse oximetry in Chapter 18.

6. Apnea monitoring

b. Perform apnea monitoring (Code: IB9p) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

Apnea monitoring is indicated in an infant who has documented periods of apnea of prematurity resulting from an immature central nervous system. This condition is most commonly seen in infants younger than 35 weeks’ gestational age. The usual monitoring guidelines include apneic periods that last longer than 20 seconds and are associated with bradycardia with a heart rate of less than 100 beats/min. Hypoxemia is often demonstrated by cyanosis, pallor, or documented desaturation through pulse oximetry. In addition, the infant may show marked limpness, choking, or gagging. Other conditions such as intracranial hemorrhage, patent ductus arteriosus, upper airway obstruction, hypermagnesemia, infection, and maternal narcotic agents, for example, should be ruled out before apnea of prematurity is confirmed. If this is the infant’s problem, it is usually outgrown by the time the infant is 40 weeks’ postconceptional age. Home apnea monitoring is not indicated in normal infants, in preterm infants without symptoms of apnea, or to test for sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). See Box 17-1 for guidelines on starting and stopping home apnea monitoring.

BOX 17-1 Guidelines for Starting and Stopping Home Apnea Monitoring

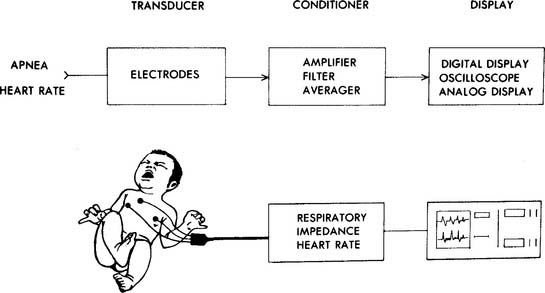

Two electrodes are usually placed where the greatest amount of movement occurs during breathing. Most often, this is on the infant’s upper chest between the nipples and armpits (Figure 17-1). With older infants, the electrodes might have to be placed on the sides over the lower ribs. Occasionally one electrode is placed on the chest and the other on the infant’s abdomen. Some monitoring systems require that a Velcro belt be placed around the infant over the electrodes to secure their positions. (Obviously this works only if both electrodes are on the chest.) Other systems employ electrodes with an adhesive. In either case, for best results, the infant’s chest should be washed with mild soap and water and dried before the electrodes are placed. This results in the best electrical conduction. Do not use baby oils, lotions, or powders over the electrode sites. Attach the lead wires to the electrodes. These connect to the patient cable that is then connected to the monitor. Occasionally static electricity causes some interference with the signal. A third chest electrode is then added to act as a ground wire.

Figure 17-1 Block diagram for impedance apnea and heart rate monitor.

(From Lough MD. In Lough MD, Williams TJ, Rawson JE, editors: Newborn respiratory care, St Louis, 1979, Mosby.)

The monitor should be plugged into a working electrical outlet and turned on. Set the unit to charge the internal battery so that it can be made portable for later use. Confirm that the infant’s respiratory and heart rates are being sensed and displayed. If pulse oximetry is a feature on the unit, the probe should be properly placed on the infant, and an Spo2 value should be displayed. Set the high and low alarm values according to the physician’s orders or established protocols. For example: