History and Physical Examination of the Venous System

Venous disease is usually localized to one anatomic area, unlike arterial disease, which is more diffuse. The lower extremities are most commonly involved, although venous problems can impair function of the upper extremities as well.

I. Upper extremities.

The most common venous conditions to affect the upper extremities are superficial and deep venous thrombosis. Superficial thrombophlebitis can result from intravenous access, which causes endothelial damage, local vein thrombosis, and subsequent inflammation of a peripheral vein. This condition rarely progresses to deep venous thrombosis and is most often self-limited, requiring local treatment in the form of warm compresses applied directly to the affected vein. Acute or chronic thrombosis of the axillary, subclavian, or innominate veins represents the upper-extremity equivalent of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and represents a serious condition. The clinician should assess for a history of prior central venous catheter or peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC lines), as these are a risk factor for the development of central venous thrombosis. The chief complaint in most cases is arm swelling. A diffuse aching pain frequently accompanies the swelling and is worse with use or dependency of the arm.

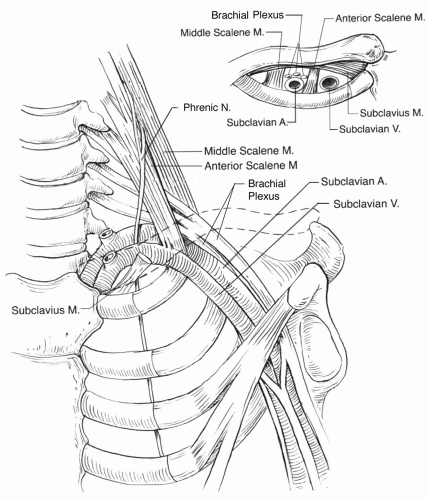

Paget-Schroetter syndrome is synonymous with effort thrombosis, and refers to the development of axillary or subclavian vein thrombosis in the setting of repetitive upper extremity exercise. Usually this form of axillo-subclavian vein thrombosis occurs acutely as a result of thoracic outlet syndrome, in which compression of the subclavian vein between the subclavius muscle underlying the clavicle and the first rib is present (Fig. 5.1). Chronic compression of the axillary or subclavian vein in these circumstances results in underlying endothelial injury and is a contributing factor to the thrombosis. Chronic arm swelling may also be the result of lymphatic obstruction, which usually is associated with a previous operation (e.g., node dissection for breast cancer), infection, or irradiation that involved the axillary lymph nodes. Distinguishing between venous obstruction and lymphedema may be difficult, although the clinical setting suggests the most likely etiology in most cases.

A. Inspection.

The examiner should inspect the arms for scars from previous indwelling venous lines or procedures and note limb size discrepancy, edema, discoloration, deformity (e.g., clavicular fracture), or venous collaterals. Subclavian vein thrombosis causes swelling of the entire arm and hand and will often result in superficial venous collateral formation across the shoulder region. Acutely, the arm may appear bluish or cyanotic, although rarely does subclavian-axillary venous thrombosis result in phlegmasia or venous gangrene. Patients in whom upper-extremity venous thrombosis leads to phlegmasia often have an underlying malignancy or hypercoagulable condition such as heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and thrombosis (Chapter 3). Following upper-extremity DVT, the arm generally does not develop venous stasis dermatitis that accompanies post-thrombotic syndrome in the lower extremities.

Another cause of acute arm swelling is placement of a hemodialysis fistula or graft in the arm that has an unrecognized venous stenosis or occlusion in the proximal or central venous outflow (Chapter 20). In such cases, completing the arterialvenous circuit for dialysis increases venous flow and pressure, which exacerbates a previously asymptomatic central venous stenosis.

B. Palpation.

The palpable cord associated with superficial thrombophlebitis of the arm is typically warm and tender. Fluctuance or purulent drainage from the cord upon palpation suggests the diagnosis of suppurative or infected thrombophlebitis,

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree