History and Physical Examination of the Arterial System

I. General Examination.

Age-related arterial disease is a diffuse process. Therefore, the exam, regardless of complaint, should include the entire arterial system in order to identify unrecognized atherosclerotic disease and should include the following:

Checking of heart rate and rhythm.

Measurement of blood pressures in both arms.

Neck auscultation to listen for carotid bruits.

Cardiac auscultation to listen for arrhythmias, gallops, and murmurs.

Abdominal palpation to assess for a pulsatile mass (e.g., aortic aneurysm).

Abdominal auscultation to listen for bruits.

Palpation of peripheral pulses.

Auscultation of the femoral region to listen for bruits.

Full length inspection of upper and lower extremities to assess for ulcers, gangrene, or evidence of distal embolization in the toes and/ or fingers (blue toe syndrome).

Measurement of leg pressures using a continuous wave Doppler and manual blood pressure cuff to calculate the anklebrachial index (ABI).

II. Head and neck.

Vascular disease in the head and neck relates mostly to atherosclerosis of the carotid arteries, which is a common cause of stroke (Chapter 13). Patients should be questioned about previous stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), carotid artery intervention (endarterectomy or stent), and prior duplex ultrasound of the carotid arteries. If a carotid intervention or duplex ultrasound has been performed in the past, the indications and results are important to understand. Symptoms of TIA or stroke typically relate to episodes of unilateral extremity weakness or paralysis. Stroke or TIA may also manifest as an inability to initiate speech (aphasia), inability to form words (dysarthria), or facial weakness or slurring of speech. The clinician should also inquire about episodes of transient monocular blindness (amarousis fugax), which would suggest

occlusive disease of the carotid artery on the same side (ipsilateral) as the ocular symptoms. Amarousis (also described as a “descending curtain or shade”) results from temporary occlusion of a retinal arteriole from emboli originating from the carotid bulb passing through the ophthalmic artery. The differential diagnosis of amarousis is broad, and includes migraine headache, papilledema, and giant cell arteritis.

occlusive disease of the carotid artery on the same side (ipsilateral) as the ocular symptoms. Amarousis (also described as a “descending curtain or shade”) results from temporary occlusion of a retinal arteriole from emboli originating from the carotid bulb passing through the ophthalmic artery. The differential diagnosis of amarousis is broad, and includes migraine headache, papilledema, and giant cell arteritis.

The differential diagnosis of stroke or TIA originating from the carotid arteries in the neck includes seizure disorder, which more commonly causes global or bilateral symptoms followed by somnolence (postictal period). Severe hypertension can lead to small vessel cerebral infarct or hemorrhagic stroke, which can be differentiated from embolic stroke from the patient’s history and presentation. Brain tumors or brain aneurysms may also cause neurologic deficits but are often accompanied by other symptoms such as headache. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DW-MRI) is useful in differentiating primary intracranial disease (small vessel cerebral infarct or brain tumor) from embolic TIA or stroke originating from carotid disease in the neck. Syncope, lightheadedness, and dizziness are common in the elderly and are referred to as posterior circulation or vertebral artery symptoms. These symptoms are rarely related to carotid disease and are more commonly due to fluctuations in blood pressure, cardiac arrhythmias, disease within the middle ear (vestibular system), or subclavian steal syndrome.

A. Inspection.

Normally, the carotid pulsation is not visible. However, it may be prominent at the base of the right neck in thin patients with longstanding hypertension. Such patients are often referred for concerns of aneurysm, when in fact they have a tortuous or prominent common carotid artery. Carotid artery aneurysm and carotid body tumor occur near the bifurcation and can be visualized in the middle or upper aspect of the anterior neck.

Another observation related to carotid occlusive disease is a bright reflective defect or spot on the retina referred to as a Hollenhorst plaque. These plaques seen on funduscopic exam of the eye were described by a Mayo Clinic ophthalmologist in the 1960s, and represent cholesterol emboli originating from atherosclerotic disease of the carotid arteries.

B. Palpation.

The common carotid pulse is palpable low in the neck between the midline trachea and the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Even in the setting of internal carotid artery occlusion, there is generally a palpable common carotid pulse as the external carotid often remains patent. A diminished or absent common carotid pulsation suggests significant proximal occlusive disease at the origin of the carotid artery in the chest. The presence of a temporal artery pulse anterior to the ear indicates a patent common and external carotid artery. Palpation itself cannot differentiate between carotid aneurysm and carotid body tumor, both of which may present as a pulsatile mass in the neck. Enlarged lymph nodes often have similar findings, and differentiation in the setting of a pulsatile neck mass requires duplex ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

C. Auscultation.

The stethoscope is placed lightly over the middle and base of the neck while the patient suspends respirations. Cervical bruits are an abnormal finding and may originate from carotid stenosis or lesions of the aortic valve or arch vessels. A bruit from a carotid stenosis is usually loudest at the midneck over the carotid bifurcation. Transmitted bruits or cardiac murmurs tend to be loudest over the upper chest and base of the neck.

The presence of a cervical bruit does not necessarily mean that a carotid stenosis is present. In fact, only half of patients with carotid bruit will have stenoses of 30% or more and only a quarter will have stenoses of more than 75%. Additionally, the severity of underlying carotid stenosis does not correlate with the loudness of the bruit. Duplex ultrasound is standard in determining the significance of a cervical bruit and is noninvasive, inexpensive, and readily available. Carotid arteriography is not used as a screening tool in the setting of an asymptomatic bruit as it is invasive and carries a risk of stroke (Chapter 13).

III. Upper extremity.

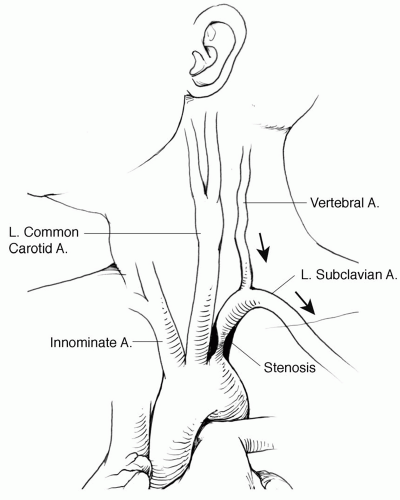

Although atherosclerosis is less common in the upper than the lower extremity, arterial lesions of the subclavian and axillary arteries can develop (Chapter 18). Upper-extremity occlusive or aneurysm disease may cause claudication or signs of embolization in the arm or hand. For reasons that are not fully understood, arterial occlusive lesions of the subclavian artery are more common on the left than the right side. In instances where a subclavian stenosis is proximal to the origin of the vertebral artery, the patient can develop a condition known as subclavian steal syndrome. In these cases exertion of the arm results in a pressure decrease across the stenosis that leads to reversal of flow in the vertebral artery (“steal”) causing posterior circulation symptoms (Fig. 4.1). Acute arm ischemia is most often the result of an embolus from a proximal arterial or even cardiac source. Acute thrombosis of a chronic subclavian or axillary artery aneurysm or stenosis may also result in acute arm ischemia.

A variety of nonatherosclerotic vascular diseases can affect the upper extremity (Chapter 18). Takayasu’s arteritis (pulseless disease) is an inflammatory condition of the arteries that occurs predominantly in young Asian women. The early stage of Takayasu’s disease is characterized by an acute inflammatory response that often includes fever, malaise, and muscle aches. The later stages occur after the acute arteritis has been treated and can result in fibrotic arterial stenoses or even arterial occlusion. Giant cell arteritis (GCA) occurs most commonly in mature Caucasian women and can affect aortic arch vessels and axillary and brachial arteries. Other symptoms associated with GCA include headaches, monocular blindness, and jaw claudication. Episodic coolness, pain, and numbness of the hand suggest small vessel vasospasm or Raynaud’s syndrome, which is often triggered by an identifiable event such as exposure to the cold. The etiology may be idiopathic (Raynaud’s disease) or associated with other systemic collagen vascular diseases or prior frostbite (Raynaud’s phenomenon).