, Douglas E. Drachman2, Douglas E. Drachman3 and Douglas E. Drachman4

(1)

Harvard Medical School Cardiology Division, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

(2)

Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA

(3)

Interventional Cardiology, Boston, USA

(4)

Cardiology Division, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Abstract

With technological advances in laboratory testing, imaging studies, and invasive procedures in cardiology, it is easy to discount the relevance of the history and physical examination. It is precisely the astute performance of the focused history and physical examination, however, that informs appropriate and efficient diagnostic testing. In the current climate emphasizing cost-effective practice, the strategic and parsimonious use of diagnostic testing is of paramount importance. Moreover, the determination of pretest probability—based on history and physical examination findings—may enhance the accuracy and clinical interpretation of subsequent diagnostic findings. In this manner, the classic teachings of the history and physical examination, coupled with the advanced capabilities of contemporary diagnostic technology, may provide optimal insight into the care of the patient.

Abbreviations

ABI

Ankle/brachial index

ACS

Acute coronary syndrome

AR

Aortic regurgitation

AS

Aortic stenosis

ASD

Atrial septal defect

AV

Aortic valve

BB

Beta blocker

BNP

B-type natriuretic peptide

BP

Blood pressure

CAD

Coronary artery disease

CI

Confidence interval

CMP

Cardiomyopathy

CP

Chest pain

CXR

Chest x-ray

DCM

Dilated cardiomyopathy

DM

Diabetes mellitus

ECG

Electrocardiogram

EP

Electrophysiology

HCM

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

HF

Heart failure

HR

Heart rate

HTN

Hypertension

JVD

Jugular venous distension

JVP

Jugular venous pressure

LA

Left atrium

LBBB

Left bundle branch block

LLSB

Left lower sternal border

LR

Likelihood ratio

LV

Left ventricle

LVEDP

Left ventricular end diastolic pressure

LVEF

Left ventricular ejection fraction

LVH

Left ventricular hypertrophy

MI

Myocardial infarction

MR

Mitral regurgitation

MS

Mitral stenosis

MV

Mitral valve

MVP

Mitral valve prolapse

OS

Opening snap

PCWP

Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure

PDA

Patent ductus arteriosus

PH

Pulmonary hypertension

PMI

Point of maximal impulse

PND

Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea

PR

Pulmonic regurgitation

PS

Pulmonic stenosis

PV

Pulmonic valve

PVD

Peripheral vascular disease

RA

Right atrium

RBBB

Right bundle branch block

RV

Right ventricle

RVH

Right ventricular hypertrophy

SOB

Shortness of breath

TR

Tricuspid regurgitation

TS

Tricuspid stenosis

TV

Tricuspid valve

VSD

Ventricular septal defect

Introduction

With technological advances in laboratory testing, imaging studies, and invasive procedures in cardiology, it is easy to discount the relevance of the history and physical examination. It is precisely the astute performance of the focused history and physical examination, however, that informs appropriate and efficient diagnostic testing. In the current climate emphasizing cost-effective practice, the strategic and parsimonious use of diagnostic testing is of paramount importance. Moreover, the determination of pretest probability—based on history and physical examination findings—may enhance the accuracy and clinical interpretation of subsequent diagnostic findings. In this manner, the classic teachings of the history and physical examination, coupled with the advanced capabilities of contemporary diagnostic technology, may provide optimal insight into the care of the patient.

History

General History

General history is comprised of the following (from the patient or the family).

Chief complaint

Common presenting symptoms for patients with suspected or known cardiovascular disease: chest pain (CP) or discomfort, shortness of breath (SOB) or dyspnea, edema, palpitations, dizziness, syncope, and fatigue or weakness.

Asymptomatic patients with incidental findings on physical examination, electrocardiogram (ECG), chest x-ray (CXR) or other imaging modalities

Asymptomatic patients who require pre-operative evaluation.

Sudden cardiac death.

Similar symptoms may stem from different underlying cardiovascular disorders and paying attention to history and examination findings will reveal clues to diagnosis.

History of the presenting illness

Description, location, onset, radiation, precipitating factors, associated symptoms, duration, alleviating factors.

Semi-quantitative assessment of symptom severity may enable serial evaluations for a change in clinical status.

Recent health status, events.

Past medical history

Known cardiac disorders

Known vascular disorders such as peripheral vascular disease (PVD) or stroke

Relevant risk factors for cardiovascular disease such as hypertension (HTN), hypercholesterolemia, metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus (DM), smoking status, obesity, exercise

Others: sleep apnea, chest surgery or radiation, mental stress.

Baseline functional capacity assessment is very important; a sedentary patient may never experience exertion-associated symptoms. Exercise capacity also has important prognostic implications [1]. Despite limitations, frequently used classification systems include the New York Heart Association classification, Canadian Cardiovascular Society classification and Specific Activity Scale [2].

Previous cardiovascular test results

ECG, echocardiogram, CXR, noninvasive imaging, stress test, catheterization, electrophysiologic (EP) evaluation.

Medications

Cardiac medications and compliance

Relevant non-cardiac medications with implications for diagnosis and management of the cardiovascular disease, such as: phosphodiesterase inhibitors taken for erectile dysfunction; anticoagulation for venous thromboembolism; metformin in patients exposed to iodinated contrast from cardiac catheterization

Allergies

Drug and contrast allergies and reaction should be documented.

Family history

Premature coronary artery disease (CAD), history of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) or sudden cardiac death.

Social history

Cocaine and alcohol intake, smoking status, job, family or home situation.

Review of systems

Neurologic, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, urinary, infectious, hematologic, immunologic, musculoskeletal, endocrine and psychiatric systems should be reviewed (Table 1-1).

Common Chief Complaints

Chest discomfort or pain (Table 1-2)

Classic angina [3]: exertional or stress-related, substernal discomfort, resolves with rest or nitroglycerin; response to nitroglycerin in the emergency department is not predictive of cardiac etiology [4] (Table 1-3).

CP equivalents: Presenting symptoms in a retrospective study of 721 patients with acute myocardial infarction presenting to the emergency department [5]

Chest, left arm, jaw, or neck complaint (53 %), SOB (17 %), cardiac arrest (7 %), dizziness/weakness/syncope (4 %), abdominal complaints (2 %), miscellaneous (trauma, gastrointestinal bleeding, altered mental status, nausea/vomiting, palpitations, and other) (17 %)

Pericarditis: abrupt onset, sharp, pleuritic and positional (better with sitting forward and worse with lying down), radiating to the back, recent fever or viral illness

Look for evidence of associated pericardial effusion (muffled or distant heart sounds) and tamponade (distant heart sounds, hypotension, jugular venous distension (JVD), dyspnea, tachycardia, pulsus paradoxus) [8]

Think constrictive pericarditis if a history of chest radiation, cardiac or mediastinal surgery, chronic tuberculosis or malignancy and right-sided heart failure (HF) symptoms/signs.

Aortic dissection: Having (1) sudden, severe, tearing CP (or equivalent), maximal at onset with radiation to the back, (2) Unequal arm blood pressure (BP) >20 mmHg and (3) Wide mediastinum on CXR had a positive likelihood ratio of 66.0 (CI 4.1–1062.0) [9]

Look for neurologic deficits, aortic regurgitation (AR), history of HTN, bicuspid aortic valve (AV), coarctation of the aorta, Marfan’s syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Turner syndrome, giant cell arteritis, third-trimester pregnancy, cocaine abuse, trauma, intra-aortic catheterization, history of cardiac surgery

Table 1-2

Life-threatening causes of chest pain

Cardiac

Non-cardiac

Acute coronary syndrome substernal, radiating to arm, dyspnea on exertion, diaphoresis, worse with exertion

Acute pulmonary embolism sudden onset, pleuritic, dyspnea, tachycardia, tachypnea, hypoxia, evidence of lower extremity deep venous thrombosis

Aortic dissection sudden onset, severe, tearing, radiating to the back (associated with neurologic deficits, AR), unequal arm BP >20 mmHg, wide mediastinum

Tension pneumothorax sudden onset, sharp, pleuritic, decreased breath sounds and chest excursion, hyperresonant percussion, hypoxia

Acute pericarditis & tamponade sudden onset, pleuritic, better with sitting forward, radiating to the back, pericardial rub, ± tamponade (distant heart sounds, hypotension, JVD)

Esophageal rupture/perforation severe, increase with swallowing, fever, abdominal pain, history of endoscopy, foreign body ingestion, trauma, vomiting

Table 1-1

Major causes of chest pain

Cardiac: ACS, aortic dissection, valvular heart disease, HF, myocarditis, pericarditis, variant angina, syndrome X, cocaine abuse, stress-induced cardiomyopathy

Pulmonary: PE, pleuritis/serositis, pneumonia, pneumothorax, reactive air way disease, PH and cor pulmonale, lung malignancy, sarcoidosis, pleural effusion

Gastrointestinal: GERD, esophageal spasm, esophageal tear or rupture, mediastinitis, esophagitis, peptic ulcer disease, cholecystitis, biliary colic, pancreatitis, kidney stones

Musculoskeletal: Costochondritis, spinal disease, fracture, muscle strain, herpes zoster

Psychogenic: anxiety, panic disorder, depression, hypochondriasis

Increase the likelihood

LR (95 % CI)

Decrease the likelihood

LR (95 % CI)

Radiates to the right arm or shoulder

4.7 (1.9–12)

Pleuritic

0.2 (0.1–0.3)

Radiates to both arms or shoulders

4.1 (2.5–6.5)

Sharp

0.3 (0.2–0.5)

Precipitated by exertion

2.4 (1.5–3.8)

Positional

0.3 (0.2–0.5)

Radiates to the left arm

2.3 (1.7–3.1)

Reproducible with palpation

0.3 (0.2–0.4)

Associated with diaphoresis

2.0 (1.9–2.2)

Palpitations [11]

Often described as flutters, heart skipping, pounding sensation

A history of cardiac disease increases the likelihood for cardiac arrhythmia (Likelihood ratio [LR] 2.0, 95 % confidence interval [CI] [1.3–3.1])

Palpitation associated with a regular, rapid-pounding sensation in the neck was strongly predictive in one study of atrioventricular nodal re-entry tachycardia with a LR of 177, 95 % CI (25–1,251)

Dyspnea

Differential diagnosis includes cardiac, pulmonary, neuromuscular, obesity, deconditioning, anemia and psychiatric.

Cardiac causes can be divided into the following

Heart failure (may be due to a variety of causes including valvular disease, arrhythmia, etc.):

Lack of adequate forward flow (fatigue, weakness, exercise intolerance)

Increased systemic venous or pulmonary pressures or congestion (dyspnea, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea [PND], abdominal discomfort from hepatic congestion or ascites, edema).

Acute HF tends to present with dyspnea while chronic HF tends to present with edema, fatigue, anorexia.

Myocardial ischemia: typically presents as dyspnea on exertion. Caused by acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or demand supply mismatch (left ventricular hypertrophy [LVH], HCM, valvular disease, bradycardia or tachycardia)

Pericardial disease: mainly due to increased pulmonary pressures

Claudication [12, 13]

Types of claudication:

Classic: exertional calf pain that resolves with 10 min of rest causes the patient to stop walking.

Atypical: non-calf pain, does not resolve with rest, does not keep the patient from walking, rest as well as exertional leg pain (concurrent DM, neuropathy, spinal stenosis)

Differential diagnosis of arm or leg pain

PVD: claudication associated with edema and skin discoloration

Other arterial disease: aneurysm, dissection, injury, trauma, radiation therapy, vasculitis, ergot use, artery entrapment/kinking (cyclists)

Deep vein thrombosis: associated with unilateral edema, pain worse with dependency

Musculoskeletal disorders: arthritis

Peripheral neuropathy: radiation of pain, sharp pain, back pain

Spinal stenosis: muscular weakness, worse after standing for a long time, back pain

In PVD, the location of the pain depends on the level of arterial narrowing (Table 1-4)

Table 1-4

Location of the arterial stenosis and the pain

Pain

Buttock or hip

Thigh

Upper 2/3 of the calf

Lower 1/3 of the calf

Foot

Location

Aortoiliac

Aortoiliac or common femoral

Superficial femoral

Popliteal

Tibial or peroneal

In new outpatients patients diagnosed with PVD 47 % did not have claudication, 47 % had atypical claudication and only 6 % had classic claudication [13].

Functional and exercise capacity determination is paramount as a patient may not have any symptoms if sedentary.

Physical Examination

General Examination

Vital signs

Any abnormality in BP, heart rate (HR), respiratory rate and oxygenation should be explored.

Blood pressure

Significant difference in pulses and BP in arms: >20 mmHg in BP is associated with aortic coarctation or dissection, subclavian artery disease, supravalvular (right > left in BP) and aortic stenosis (AS)

Significant difference in the pressure in legs compared with arms: >20 mmHg higher than arms is associated with the Hill sign in severe AR or extensive and calcified lower extremity peripheral arterial disease. A delay in pulse from radial to femoral in a patient with HTN is associated with aortic coarctation

Pulse pressure is defined as systolic pressure – diastolic pressure

Wide pulse pressure is associated with AR, older age, atherosclerosis

Narrow pulse pressure is associated with HF (a pulse pressure of <25 % of the systolic pressure is associated with a cardiac index of <2.2 L/min/m2) [14], HCM

Orthostatic blood pressures: measure BP and HR after standing for 1–3 min.

Orthostatic hypotension: a drop in systolic BP >20 mmHg, a drop in diastolic BP >10 mmHg or HR rise >10 bpm.

Valsalva response

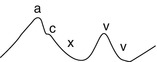

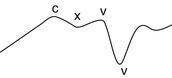

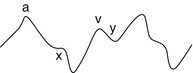

Normal Valsalva sinusoidal response (Fig. 1-1)

Figure 1-1

Normal valsalva sinusoidal response. BP blood pressure (Courtesy of Dr. Hanna Gaggin)

Abnormal response pattern (in patients not taking a beta blocker [BB])

Absent overshoot response: no Phase 4 rise in systolic BP, associated with moderately decreased left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF)

Square wave response: presence of Korotkoff sounds during the entire straining phase and no Phase 4 rise in systolic BP, associated with severely decreased LVEF

Pulsus paradoxus

Fall in systolic BP >12 mmHg with inspiration has a sensitivity of 98 % and specificity of 83 % for the diagnosis of pericardial tamponade [8]

Can also be positive in hypovolemia, anything that results in right-sided failure (pulmonary embolism, chronic lung disease), constriction, HF

General appearance

The first assessment before any history or physical examination should be the global overview. Is the patient acutely ill? Diaphoresis, tachypnea, cyanosis, decreased mental status all signify serious conditions. The result of this assessment will determine how focused and timely the history and examination should be.

The skin

Identify evidence of poor perfusion such as cold and clammy skin (cardiogenic shock, HF or PVD), cyanosis (congenital heart disease or shunts), bronzing of the skin (iron overload or hemochromatosis), ecchymoses (antiplatelet or anticoagulation medication), xanthomas (hypercholesterolemia), lupus pernio, erythema nodosum or granuloma annulare (sarcoidosis).

Look for dialysis fistulas (end stage renal disease and in acutely ill patients, likely metabolic disarray).

Skin findings that increase the likelihood of PVD [15]

Cool to touch LR 5.9 (95 % CI 4.1–8.6)

Wounds or sores LR 5.9 (95 % CI 2.6–13.4)

Skin discolorations LR 2.8 (95 % CI 2.4–3.3)

Head and neck

Elevated jugular venous pressure (HF), high arched palate (Marfan’s), large protruding tongue (amyoloidosis), ptosis and ophthalmoplegia (muscular dystrophies), hypertelorism, low-set ears, micrognathia, webbed neck (Noonan, Turner and Down syndromes), proptosis, lid lag and stare (Grave’s hyperthyroidism).

Jugular venous pressure (Table 1-5)

Calculation of jugular venous pressure (JVP) in mmHg

1.

Determine vertical distance above the sternal angle to the top of the venous pulsation (in cm water)

3.

Divide by 1.36

Normal RA pressure is <8 mmHg

Clinical assessment of the presence of an elevated JVP (rather than exact JVP) is fairly accurate in predicting elevated right atrial (RA) pressure and the pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP)

JVP <11 cm in predicting invasively measured RA pressure <8 mmHg: negative predictive value =82 % [17]

Presence of elevated JVP at rest or hepatojugular reflux in predicting PCWP >18 mmHg: sensitivity =81 %, specificity =80 %, predictive accuracy =81 % (in the absence of cirrhosis, volume overload in renal diseases and right-sided cardiac disease) [18]

When three or more signs (JVD, S3, tachycardia, low pulse pressure, rales, abdominojugular reflux), >90 % likelihood of increased filling pressures if severe left ventricular (LV) dysfunction was not known. 1 or 0 symptoms or signs <10 % likelihood of increased filling pressures [19]. In chronic HF, rales, edema, JVD and pulmonary edema on CXR can be often absent.

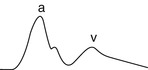

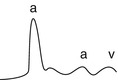

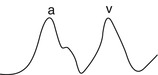

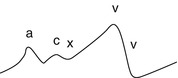

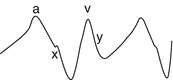

Table 1-5

Jugular venous waveforms

Finding and RA tracing

Examples

Normal

Prominent a wave

Obstruction to RA emptying

TV abnormalities: TS, RA myxoma, carcinoid heart disease, lupus endocarditis, RA thrombus, tricuspid atresia

Distal to tricuspid valve: decreased RV compliance such as in RVH, RV outflow obstruction such as in PS

PH

Uncommon in conditions with VSD or ASD

Cannon a wave

RA contraction against a closed TV

A-V dissociation

Premature atrial, junctional or ventricular beats

1st degree AVB

Flutter a wave

Atrial flutter

Absent a wave

No effective atrial contraction

Atrial fibrillation

Ebstein’s anomaly

Equal a wave and v wave

ASD

TR

Prominent v wave

ASD without PH

Prominent × descent

ASD

Early cardiac tamponade

Blunted or absent y descent

Late pericardial tamponade

TS

Severe RVH

Steep y descent

Constrictive pericarditis (classic M or W contour with prominent x and y descents)

Restrictive cardiomyopathy

Severe right side HF

TR

Chest

Look for venous collaterals (venous obstruction), pectus carinaturm or excavatum (connective tissue disorders), barrel chest (emphysema), kyphosis (ankylosing spondylitis)

Abdomen

Hepatomegaly and ascites (right-sided HF, constrictive pericarditis), enlarged abdominal aorta (the positive predictive value for abdominal aortic aneurysm is only 43 % [20])< div class='tao-gold-member'>Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree