Histiocytic Tumor Proliferations of the Lung

Marie-Christine Aubry, M.D.

Allen P. Burke, M.D.

Rima Koka, M.D., Ph.D.

Overview

The differential diagnosis of histiocytic proliferations of the lung is broad (Table 92.1). The main consideration for neoplastic histiocytic proliferations include Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD), Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), and other histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms. These neoplasms are rare and less common than nonneoplastic proliferations of histiocytes.

Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Clinical

RDD, previously known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, is a disease that primarily involves lymph nodes, especially of the neck.1,2 Most patients present with lymphadenopathy and systemic symptoms of fever and weight loss. Extranodal manifestations occur in 43% of patients, while in 23%, there is no lymph node disease.3 Pulmonary involvement is uncommon and has been reported in only 2% of patients.4

Pulmonary manifestations include an incidental mass, either with or without systemic symptoms resulting from lymph node involvement,3,5 stridor secondary to airway compression,6 cough, and syncope.4,7 Pulmonary artery involvement has been reported.4,7

The prognosis for RDD in general is excellent; however, patients with lung involvement may develop progressive disease, resulting in their death.2

Radiologic Findings

The imaging findings are variable and include parenchymal nodules, pleural thickening, and pleural effusions.1,2

TABLE 92.1 Histiocytic Proliferations of the Lung | |

|---|---|

|

Microscopic Findings

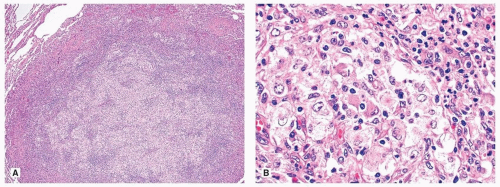

Histologic findings are those of extrapulmonary lesions. The infiltrates may be nodular (Fig. 92.1) or interstitial, composed of abundant macrophages with large pale cytoplasm, in a background of small lymphocytes, plasma cells, and variable fibrosis. The distinguishing feature of RDD is emperipolesis which is characterized by lymphocytes or neutrophils in the cytoplasm of the macrophages (Fig. 92.1).

Immunohistochemically, the macrophages are typically positive for CD68, CD14, and S100 protein. They are usually negative for CD1a and other dendritic markers such as CD21 and CD35, helpful findings for the differential diagnosis (Table 92.2). IgG4 plasma cells may be prominent, underscoring the lack of specificity of this finding.5,8,9

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes other monocytic and histiocytic diseases such as LCH, ECD (see below), IgG4-related diseases (Chapter 51), and lymphomas, particularly Hodgkin lymphoma.

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis and Sarcoma

General

LCH is a clonal neoplastic disorder seen primarily in children and young adults. LCH is classified according to the sites of involvement. The disease may be localized to one organ, most commonly bone; it may involve multiple sites in one organ system or involve multiple organs (such as diseases previously known as Hand-Schüller-Christian disease or Letterer-Siwe disease). Rarely, the Langerhans cell proliferation may be highly aggressive and the morphology of the Langerhans cells may be overtly malignant warranting a diagnosis of Langerhans cell sarcoma.

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis (PLCH) (Chapter 24) differs from most LCH and yet has some overlapping features. Indeed, some adults with PLCH have been described to have co-occurring diabetes insipidus, bone lesions, and skin involvement.10,11,12 Like LCH, BRAF mutation is present but only in a subset of cases.13,14,15 In contrast to other LCH, PLCH is strongly linked to cigarette smoking.1 In fact, patients with PLCH and bone lesions have seen their bone lesions regress with smoking cessation.16

Clinical

LCH occurs predominantly in children, adolescents, and young adults. The lungs are involved in fewer than 5% of children over 2 years with multiorgan LCH and fewer than 25% of children under 2 years.17 LCH in children is never isolated to the lungs,17 although an adolescent with disease limited to nails and lung has been reported.18 In children with significant pulmonary disease, multisystem involvement is invariably present.19

The self-limited congenital form of LCH that involves the skin20 only rarely involves the lungs.21

The self-limited congenital form of LCH that involves the skin20 only rarely involves the lungs.21

Although lung involvement is considered a “risk organ,” lung lesions generally result primarily in pneumothorax and do not significantly reduce survival.17 Other “risk organs” include the liver, spleen, and bone marrow, with multiple “risk” organ involvement imparting a poor prognosis. Most frequent “nonrisk” organs are bones, skin, and pituitary gland, the last resulting in diabetes insipidus.

Langerhans cell sarcoma is mainly a disease of the adult. Although skin and soft tissue are most commonly involved, multiorgan involvement may occur. In a review of the world literature, lung involvement occurred in 2 of 28 reported cases.22

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree