The association between circulating levels of cardiac troponins and angiographic severity of coronary artery disease (CAD) has not been studied. We investigated whether there is an association between the level of high-sensitivity troponin T (hs-TnT) and angiographic severity of CAD and whether this association is independent of conventional risk factors, N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT–pro-BNP) and C-reactive protein (CRP). This case–control study included 904 patients with stable CAD (cases) and 412 patients with chest pain but without significant CAD on coronary angiogram (controls). Diagnosis of CAD was confirmed or excluded by coronary angiography. Cardiac TnT was measured with conventional and high-sensitivity assays in parallel using the same plasma sample. In patients with no CAD and in those with 1-, 2-, or 3-vessel disease, hs-TnT levels (median, twenty-fifth to seventy-fifth percentiles) were 0.005 μg/L (<0.003 to 0.009), 0.006 μg/L (0.003 to 0.011), 0.008 μg/L (0.004 to 0.013), and 0.010 μg/L (0.006 to 0.017), respectively (p <0.001). In multivariable analysis adjusting for cardiovascular risk factors and clinical variables including NT–pro-BNP and CRP, hs-TnT was an independent predictor of presence of CAD (adjusted odds ratio 1.30, 95% confidence interval 1.07 to 1.59, p = 0.009). In conclusion, in patients with stable and angiographically proved CAD, hs-TnT level is increased compared to subjects without CAD and correlates with angiographic atherosclerotic extent and burden. The association between increased levels of hs-TnT and presence of CAD was independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors, NT–pro-BNP, and CRP.

Cardiac troponins are preferred biomarkers for the diagnosis of acute myocardial injury. The recently developed high-sensitivity troponin assays have enabled measurements of slight troponin increases in most healthy subjects and patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD). High-sensitivity troponin assays have improved early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction and have a decisive role for diagnosis, risk stratification, and selection of appropriate revascularization strategies in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Population-based studies have demonstrated a strong association between high-sensitivity troponin levels and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality that is independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors, setting the stage for a potential role of cardiac troponins in primary prevention. Based on these findings, Apple recently proposed considering high-sensitivity cardiac troponin a risk factor alongside conventional risk factors such as smoking, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. Few studies with limited numbers of patients have investigated the relation between circulating levels of cardiac troponins and extent of CAD and the results have been contradictory. In this study, we investigated whether there is an association between the level of high-sensitivity troponin T (hs-TnT) and angiographic severity of CAD and whether this association is independent of conventional risk factors, N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT–pro-BNP), and C-reactive protein (CRP).

Methods

This is a case–control study. Diagnosis of CAD was confirmed or excluded by coronary angiography. Cases consisted of a consecutive series of 904 patients with stable (angina symptoms without change in pattern over the previous 2 months) and angiographically proved CAD (coronary stenoses with ≥50% lumen obstruction in ≥1 of 3 major coronary arteries). Controls included 412 consecutive patients with chest pain suggestive of ischemic heart disease without previous myocardial infarction or coronary revascularization who underwent coronary angiography that resulted in arterial vessel irregularities of <25% luminal narrowing at most and without regional left ventricular wall motion abnormalities. Exclusion criteria have been reported in another publication from our group. Cases and controls were collected over the same period (from January 2005 through February 2006). The study was conducted according to principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institutional ethics committee. All patients gave informed consent for angiographic examination and plasma collection. Blood samples were obtained at the time of cardiac catheterization before angiographic examination. The hs-TnT and NT–pro-BNP assay kits were donated by Roche Diagnostics (Mannheim, Germany); however, the company had no role in the study conception or design, analysis of the data, or the preparation or decision to submit the report.

Diagnosis of stable CAD was based on the reporting of chest pain that did not change its pattern during the previous 2 months in a patient with angiographic evidence of CAD. Arterial hypertension was defined as active treatment with antihypertensive agents or as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg. Hypercholesterolemia was defined as a documented total cholesterol concentration ≥240 mg/dl. Diabetes was defined if patients were under treatment with insulin or hypoglycemic agents. For patients on dietary treatment alone, documentation of abnormal fasting blood glucose levels or abnormal glucose tolerance test result according to World Health Organization criteria was required for the diagnosis of diabetes. Glomerular filtration rate was estimated using the Cockcroft–Gault formula. Severity of heart failure was assessed according to the New York Heart Association.

Digital angiograms were analyzed offline with an automated edge-detection system (CMS, Medis Medical Imaging Systems, Nuenen, the Netherlands) in the core laboratory by operators who were unaware of patients’ clinical characteristics. Patients were classified as having no CAD (coronary artery irregularities with <25% lumen obstruction) or 1-, 2-, or 3-vessel disease depending on the number of main coronary arteries with ≥1 coronary stenosis with ≥50% lumen obstruction. Angiographic atherosclerotic burden was quantified using the Gensini score, which considers severity of narrowing and number and importance of narrowed vessels. Global left ventricular ejection fraction was determined by left ventricular angiography using the area–length method.

Blood samples were collected into tubes containing lithium-heparin as an anticoagulant. Within 30 minutes blood was centrifuged at room temperature, and the plasma supernatant was immediately separated and stored frozen at −80°C until analysis. Plasma concentration of cardiac TnT was quantitatively determined using the Elecsys/Cobas e cardiac TnT fourth-generation enzyme immunoassay and the new high-sensitivity assay (Roche Diagnostics) in a Cobas e 411 immunoanalyzer based on electrochemiluminescence technology (Roche Diagnostics) according to instructions of the manufacturer (conventional fourth-generation TnT: detection limit 0.01 μg/L, ninety-ninth percentile level <0.01 μg/L, and ≤10% coefficient of variation level 0.03 μg/L; hs-TnT: detection limit 0.003 μg/L, ninety-ninth percentile level 0.014 μg/L, and ≤10% coefficient of variation level 0.013 μg/L). NT–pro-BNP measurements were performed in a Cobas e 411 immunoanalyzer (Roche Diagnostics). Functional sensitivity is <50 pg/ml. Quantitative determination of CRP was performed in a Cobas Integra 800 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics). The CRP assay is based on the principle of particle-enhanced turbidimetric measurement, where human CRP agglutinates with latex particles coated with monoclonal anti-CRP antibodies. The lower detection limit of the assay is 0.71 mg/L. Expected values for adults are <5 mg/L. Other biochemical measurements were performed using routine commercially available tests.

Data are presented as median (interquartile range) or count (percentage). Normality of data distribution was assessed using 1-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Categorical data were compared using chi-square test. Continuous data with skewed distribution were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed to estimate the area under curve of hs-TnT and NT–pro-BNP regarding presence of CAD. Differences between areas under the ROC curve were assessed for statistical significance according to the method by DeLong et al. Multiple logistic regression model was used to identify correlates of presence of CAD. The following variables were entered into the model: age, gender, diabetes, arterial hypertension, body mass index, hypercholesterolemia, smoking, CRP, glomerular filtration rate, NT–pro-BNP, and hs-TnT. Values for hs-TnT and NT–pro-BNP were entered into the model after logarithmic transformation. All analyses were performed using S-PLUS (Insightful Corporation, Seattle, Washington). All tests were 2-tailed. A p value <0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

Results

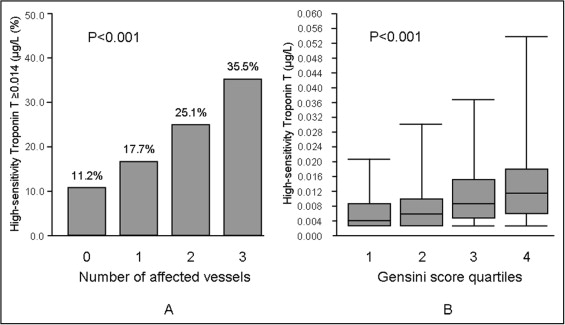

The study included 1,316 patients (904 patients with stable CAD and angiographic evidence of CAD and 412 patients presenting with chest pain and without CAD on coronary angiogram). Cases consisted of 130 patients with 1-vessel CAD, 227 patients with 2-vessel CAD, and 547 patients with 3-vessel CAD. Baseline characteristics of patients are listed in Table 1 . With the exception of proportions of patients with arterial hypertension and current smoking and values of body mass index and systolic blood pressure, which did not differ significantly between groups, all other characteristics appeared to differ significantly, showing a more adverse cardiovascular risk profile in the case group than in the control group ( Table 1 ). Of note, conventional TnT level was detectable in only 2.7% of subjects with no CAD and increased progressively up to 9.9% in patients with 3-vessel CAD. In the remaining patients cardiac troponin was not detectable using the conventional troponin assay. The hs-TnT level increased progressively with the increase in the number of narrowed coronary arteries. The hs-TnT level was higher than the upper reference limit (ninety-ninth percentile) in 11.2% of subjects with no CAD and increased progressively to 35.5% in patients with 3-vessel CAD ( Figure 1 , Table 1 ).

| Variable | Number of Coronary Arteries Narrowed | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| (n = 412) | (n = 130) | (n = 227) | (n = 547) | ||

| Age (years) | 63.3 (54.1–70.1) | 66.3 (58.7–74.2) | 68.5 (62.1–75.8) | 67.4 (61.3–74.0) | <0.001 |

| Women | 208 (50.5%) | 45 (34.6%) | 75 (33.0%) | 89 (16.3%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 67 (16.3%) | 28 (21.5%) | 57 (25.1%) | 162 (29.6%) | <0.001 |

| Arterial hypertension | 292 (70.9%) | 85 (65.4%) | 162 (71.4%) | 388 (70.9%) | 0.617 |

| Smoker | 133 (32.3%) | 58 (44.6%) | 81 (35.7%) | 235 (43.0%) | 0.002 |

| Current smoker | 48 (11.7%) | 24 (18.5%) | 22 (9.7%) | 68 (12.4%) | 0.103 |

| Hypercholesterolemia (≥240 mg/dl) | 256 (62.1%) | 80 (61.5%) | 169 (74.4%) | 439 (80.3%) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) | 27.1 (24.3–30.2) | 27.0 (24.1–29.4) | 27.0 (24.7–29.7) | 26.9 (24.8–29.7) | 0.930 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 0 | 29 (22.2%) | 66 (29.1%) | 239 (43.7%) | <0.001 |

| Previous coronary artery bypass grafting | 0 | 1 (0.8%) | 2 (0.9%) | 138 (25.2%) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 152.0 (140.0–170.0) | 153.0 (130.0–174.2) | 150.0 (135.0–170.0) | 152.5 (132.0–174.0) | 0.994 |

| New York Heart Association class | <0.001 | ||||

| I | 313 (76.0%) | 90 (69.2%) | 151 (66.5%) | 327 (59.8%) | |

| II | 91 (22.1%) | 35 (27.0%) | 70 (30.8%) | 197 (36.0%) | |

| III | 7 (1.7%) | 5 (3.8%) | 6 (2.7%) | 23 (4.2%) | |

| IV | 1 (0.2%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 80.0 (70.0–83.0) | 72.0 (66.0–80.0) | 80.0 (70.0–90.0) | 80.0 (70.0–90.0) | <0.001 |

| Low-density lipoprotein (mg/dl) | 116.0 (96.3–140.0) | 105.0 (83.8–135.5) | 94.4 (75.2–121.0) | 91.8 (72.8–122.0) | <0.001 |

| High-density lipoprotein (mg/dl) | 55.5 (45.9–66.5) | 56.4 (46.3–62.8) | 52.4 (43.7–67.0) | 49.0 (41.5–58.9) | <0.001 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 1.82 (0.93–4.06) | 1.41 (0.71–2.78) | 1.58 (0.85–3.52) | 1.96 (0.85–4.22) | 0.029 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | <0.001 |

| Glomerular filtration rate (ml/min) | 97.0 (77.0–120.1) | 87.8 (69.8–111.9) | 82.8 (63.8–104.4) | 85.4 (65.7–107.3) | <0.001 |

| N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (ng/L) | 143.4 (63.1–378.2) | 170.5 (74.5–370.2) | 246.2 (103.1–633.1) | 285.5 (130.8–746.3) | <0.001 |

| Conventional (fourth-generation) troponin T (μg/L) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | — |

| Conventional troponin T ≥0.01 μg/L | 11 (2.7%) | 6 (4.6%) | 14 (6.2%) | 54 (9.9%) | <0.001 |

| High-sensitivity troponin T (μg/L) | 0.005 (0.003–0.009) | 0.006 (0.004–0.011) | 0.008 (0.004–0.013) | 0.01 (0.006–0.017) | <0.001 |

| High-sensitivity troponin T ≥0.014 μg/L | 46 (11.2%) | 23 (17.7%) | 57 (25.1%) | 194 (35.5%) | <0.001 |

| High-sensitivity troponin T ≥0.013 μg/L | 52 (12.6%) | 27 (20.8%) | 64 (28.2%) | 214 (39.1%) | <0.001 |

| Statin therapy on admission | 158 (38.3%) | 70 (53.8%) | 156 (68.7%) | 452 (82.6%) | <0.001 |

| Gensini score | 0.0 (0.0–1.5) | 9.3 (6.0–17.8) | 16.5 (10.5–26.0) | 38.0 (17.5–74.3) | <0.001 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 63.0 (60.0–66.0) | 60.0 (56.0–65.0) | 60.0 (53.0–64.0) | 57.0 (48.0–61.5) | <0.001 |